by R. Passov

After Steve Jobs hit his VP of development on the forehead, called him a stupid fuck, then stormed out of a meeting that had been set up to see George’s invention, everything changed.

The invention, George said, was on the motherboard. Dell and HP were buying 40 million so that no matter where you were in the world you could grab the local, over-the-air broadcast signal and with a little software, read the signal by the hardware, turning your computer into a TV.

By 2005, Jobs didn’t want anyone reaching out over the air. He wanted everyone to come through the Apple store. Apparently, neither his VP of development or George knew that. On its way toward bankruptcy, CrestaTech ate a fortune.

* * *

Back in the early 1990’s, before one of Sun Microsystems frequent purges forced me out, I shared an office with George and a fellow named Hung Gee. I came to understand something of what George labored on; learning the arc of his career from Daisy Systems – an innovator in microchip design tools – through to Sun where he managed a small corner of the Scalable Processor Architecture or SPARC Chip. As the geometry of microprocessors shrank, electrons traveled shorter distances. The non-intuitive result was to ask less of the hardware (the microprocessor) and more of the software.

Hung Gee was harder to pierce. George believes he can trace Hong Gee’s path to the parking lot of MIPS, another architectural innovator, and to the day in that parking lot when a man with the same name as Hong Gee shot his boss.

* * *

Fifteen years after that fateful meeting with Jobs, early in the first winter of Covid, during a teaching stint at Berkeley, I reached out. George looked the same, like a tiny-tike wrestler. No form, just a solid mass, topped by an orange mop, impossibly lighter than a carrot, and mad, blue eyes.

Over a long, winey lunch at an empty restaurant he caught me up on his last decade. I had lost count of his children. He has five; two with his new wife, three with his ex, who after nearly two decades of not speaking, was civil at his third child’s college graduation. Finally, George said, finally.

Then, we moved to his life story.

A Jewish organization paid $5,000 to the Romanian government as compensation for his high school education. In return, George was allowed to emigrate.

At twenty, he landed in Israel and entered the Technion where he managed his mandatory army service programing a computer. Though it lacked the requisite parts to be turned on, according to his commander, that was ok.

George had come to Israel from a small town outside of Bucharest. He was the only child of a housewife and an engineer who managed to coax electricity out of an aging plant, down into the Village. It offered a living, George said, enjoyed by parents happy war was finished.

Before I left, George offered, my mother and I went through family pictures. When she found a picture of her best friend she said, “The bitch.”

“After all those years,” George explained, “first she remembered that woman had been in love with my father, then remembered she how died at Auschwitz.”

George’s father was the youngest in a family of three children. Lacking means, his parents sent him to an orphanage. During the war, the orphanage sent him to a work camp in Russia. He survived. Since the Russians needed the labor more than the Germans they were less likely to kill you.

George’s maternal grandmother chose for her husband a blacksmith over a doctor. While her relatives luxuriated in the Romanian country side, she fought disease and starvation. When the Hungarians sent the Romanian Jews to the camps, the peasants, not new to starvation, survived. The rich dropped like flies.

His mother’s family had let a destitute family stay in a shed on their farm. When they returned after the war, the poorer family said the Germans should have killed them but since the Germans hadn’t, if they tried to take their land back they’d do what the Germans should have done. That, his mother said, hurt more than everything else. But the pain didn’t last. Soon, the communists made everyone equal.

* * *

“I am selling my house,” George offered.

Then what? I asked.

Then, George said, I’m going to take my family around the world. “Why not?”

I offered a few reasons. His youngest daughters, 13 and 10, might not like a year of hotel living, might miss their friends. And, I asked, what are you going to find?

“A place to start over,” George said.

To start over because, aside from the Palo Alto mansion designed by his ex, of a once vast fortune, little remains.

* * *

As the second winter of Covid approached, George and I walked the campus of Princeton. After selling his house, he had driven his wife and two of his five children across the country. He knew someone in Princeton, a friend from way back, when they were teenagers in Romania running an underground disco.

I recorded our conversation. Halfway in, George’s phone rang and my recording ceased working. Maybe he has a device so that only half of what I had captured remains: when I remind him about suggesting, before anyone had heard of iPods, that we store music in DRAM, or when he finally tells me how he got porn onto the CD, from someone at SoftBank, he said, who had a business.

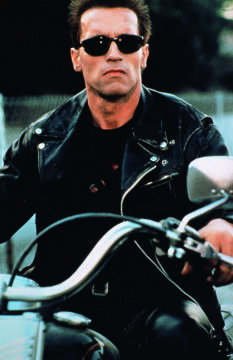

The very first video I saw played on a computer, about the very first time anyone saw video played through a computer – George built the software that decompressed video enough to fit inside a computer – was a snippet of Arnold Schwarzenegger on his motorcycle, taken from the terminator, maybe 10 seconds. Not long after, I witnessed someone in Intel’s business development group, at an open cubicle, watching an act of fellatio, smiling that greedy giddiness young men get when they think they’ve found the future.

* * *

In Romania, George said he always looked west, away from communism and toward rock and roll and ‘chicks.’ In that one aspect, getting to the West was a huge let down. ‘Chicks,’ apparently, are much more approachable under communism.

After the Technion, George landed at Zoran, one of the early leaders in digital signal processors, or DSP chips – microprocessors designed for the special tasks so necessary in our social media milieu.

Zoran was a good fit. George nurtured his passion for disco, amplifiers and western music. But Israel wasn’t far enough west. Whenever he had time George dreamed of Intel, then rising above the Silicon Valley, shining over all else in the land of computers.

“As a devoted Muslim seeks Mecca, a devoted tech wants to live in the Silicon Valley.” “Plus,” said George, “there’s rock and roll and the blues.”

While working to enable a floating-point implementation – a trick in mathematical notation that helps computers handle very large or very small numbers – George was given an opportunity to visit headquarters in Palo Alto. There, after witnessing the demand for his skills, he printed a dozen resumes that he would hand out at a coffee shop. Right away he got an offer from Daisy.

* * *

Back in the day when the Silicon Valley was all about hardware, Daisy was a famous way station. Dave Stamp, of Intel fame, started Daisy with the intention of building a ‘workstation’ – in this case a special purpose computer designed to aid in computer chip design.

According to George, while the idea was good, the business model was backwards. In order to get customers to buy the workstation, Daisy gave away the software. George wrangled an invitation to a Senior Staff Meeting. There, he let everyone know the business model was upside down.

Dave wanted engineering from George, not marketing. But that was ok. Vinod Khosla, another Daisy employee in that meeting, was already on his way to co-founding Sun. Reading the tea leaves, George decided to follow.

* * *

Everything that happens inside a computer is an algorithm for something wanted on the outside. According to George, one day his intuition told him that people wanted to see things on their computers move.

Nurturing his intuition through sleepless nights, he got a run at Sun’s Architectural Review Board, then consisting of such luminaries as Eric Schmidt, one day to be responsible for a lot of what would happened at Google, and Andy Bechtolscheim. At Sun, the Network was the Computer and no one more so than Bechtolscheim understood the combination of hardware and software making that happen.

Of course, to get to the Architectural Review Board, George stepped over his boss. His proposal was innovative: Break the 32 bit-wide data path of the SPARC chip into 4 streams, each eight bits wide. The result was a 5x improvement in painting pixels on a screen. The Moving Pictures Experts Group, or MPEG, was just beginning their work to standardize video decompression on computers. George’s innovation would make a big difference.

Not long after that meeting, Bechtolscheim wrote George a check, very much like how he wrote a check that, when handed through his car window to two kids he barely knew, helped launched Google.

* * *

George took the check and launched his first start-up – CompCore – which succeeded, through elegant math and brutish effort, to build, perhaps, the very first MPEG-standard video decompression software program, allowing the 10 second clip of Schwarzenegger to make its way around the Valley.

I took my severance and stumbled into Intel’s Venture Capital Group. For comic relief, every now and then, after George called, conspicuously wearing a suit, I’d leave my office and pretend I was his CFO. Beyond looking the part, I had nothing to add.

But there I was, one of four, inside a dark office on the second floor, at the back of a strip mall, once a motel. George sat to my left. We looked across to Vinod and Andy.

By the time we were sitting around that table, Vinod had transformed into a wonder boy, directing Kleiner Perkins, then earning the reputation that once made it the most venerable of Silicon Valley VCs’, since lost to the squabbling of rich, old men.

Andy’s introduction was simple: “Show him the software, George.” He showed – 10 seconds of Schwarzenegger, riding that Harley.

It would take more than that to impress the wily Khosla. “It’s just a point solution,” he offered. “Nothing more.” Then added, “You won’t get customers.”

Khosla never looked my way, but it wouldn’t have mattered. I wasn’t the real deal. Though I thought he was right, his arrogance left me wishing otherwise.

At the very moment when my wish morphed into that all too familiar feeling of inferiority, George took the bait. “You’re wrong!” he said. “I’ll show you,” dragging the “I’ll” through his Romanian English.

He reached into his briefcase and found a CD. “Already,” he said, “one hundred million Chinese are using the software.” Which was not true simply because, in 1996, likely less than a five-thousand Chinese had a personal computer. *

Next to our small round table, George’s computer sat on a cluttered desk. We swiveled our attention as George inserted the CD. The disk spun, whizzing the software into the computer, letting it be one of the very first to play back raw, Chinese porn.

“You are wrong,” said George. “One hundred million Chinese are looking at this right now. Right now!”

——————————-

* I estimate less than 4,000 pc’s in China.