by Rafaël Newman

You’ve heard the story before. The poet Orpheus, celebrated for the enchanting quality of his voice, is grieving the sudden death of his young wife Eurydice. In his despair he resolves to harrow the Underworld, where he so impresses the god Hades with his singing that he is permitted to retrieve the shade of his bride and return with her, newly embodied, into the light—on one condition: that he not look back at Eurydice until they have attained the realm of the living. All is proceeding according to plan, and the pair have nearly made it to the world above, when Orpheus, overcome by the suspicion that he has been swindled, turns to assure himself that his silent wife is still following him—only to see her flee away, this time forever, back into the shadows.

You’ve heard the story before. The poet Orpheus, celebrated for the enchanting quality of his voice, is grieving the sudden death of his young wife Eurydice. In his despair he resolves to harrow the Underworld, where he so impresses the god Hades with his singing that he is permitted to retrieve the shade of his bride and return with her, newly embodied, into the light—on one condition: that he not look back at Eurydice until they have attained the realm of the living. All is proceeding according to plan, and the pair have nearly made it to the world above, when Orpheus, overcome by the suspicion that he has been swindled, turns to assure himself that his silent wife is still following him—only to see her flee away, this time forever, back into the shadows.

Boy meets girl.

Boy loses girl.

Boy finds girl.

Boy loses girl again.

Boy founds enduring aesthetic tradition.

For the theme of the beautiful, irretrievable, now permanently dead woman and her endlessly grieving, magically gifted male lover, who nobly commemorates her in works of art, has been recycled time and again in the millennia since its mythical origins, in story, song, and the visual media, from the Roman elegists through the earliest Venetian opera pioneers to the Romantic poets, from the painters of the Renaissance through the Pre-Raphaelites to the Surrealists.

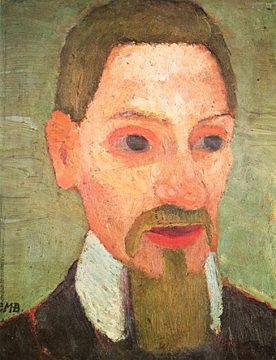

Among those who have retold the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice in recent times is Rainer Maria Rilke. In his poem “Orpheus. Eurydike. Hermes,” from Neue Gedichte (1907), written in the ferment of a young century in which Eros and Thanatos had won a newly legitimate purchase on the minds of central European modernists, under the burgeoning influence of psychoanalysis, the poet imagines Eurydice so consumed by her own death, so replete with the pleasure of Being dead, which fills her like a child, that she misses the moment of her own second demise, her failed redemption at the hands of her careless lover, whose very name she has forgotten in the deliciousness of her posthumous reverie:

She was deep within herself, like a woman heavy

with child, and did not see the man in front

or the path ascending steeply into life.

Deep within herself, Being dead filled her beyond fulfillment.

…

And when, abruptly,

the god put out his hand to stop her, saying,

with sorrow in his voice: He has turned around—,

she could not understand, and softly answered

Who?

Eurydice’s beautiful death, in Rilke’s reimagined scenario and in his later writing, will come to represent a double, fantasy fulfillment: of the male artist’s own fruitless wish for respite from the cares of embodied existence, and of his fruitful conjuring of the beautifully narcissistic, worthily still form of the feminine, pregnant with her own aesthetically productive death. This modernist rewriting of the Orpheus myth, therefore, despite its shift of focus from the living poet’s perspective to that of his dead wife, and for all of the historical Rilke’s relatively emancipated relations with the artistically active women in his private life, simply more radically reinstates the ancient tradition of mute female object mourned by speaking male subject, even as it coopts the biological phenomenon of pregnancy for rhetorical ends.

It is this tradition that Renée Thorne challenges in Eurydice, Alive, a new and bijou volume in a series of artist’s editions from a small Lausanne publishing house. In brief sketches, Thorne offers a compressed memoir of her cloistered upbringing in a conservative religious community in rural California, and her subsequent flight to an independent, secular adulthood in Seattle, inventively interwoven with an account of the short life of Paula Modersohn-Becker (1876-1907), the German modernist painter and friend of Rilke’s who left her own pre-ordained role as wife for an independent life as an artist. Along the way, Thorne also recounts vivid details of Rilke’s peculiar childhood and his marriage to the sculptor Clara Westhoff; and she hints at her own eventual liberation from the twin trammels of traditional sex roles, and of an androcentric construction of artistic creation, in the artist’s life that will encompass the creation of this elegant and absorbing chapbook.

The volume begins, however, jarringly, after an initial prologue setting out the Rilkean motif, with the accidental death of Thorne’s mother. The blunt fact of the terrible event, which occurred while the young woman was scuba diving with her husband, Thorne’s father, is offered in the early pages of the text with abrupt brutality. It follows and stymies Thorne’s hopeful account of the young couple’s further family planning, after the births of the author and her brother, and announces one of Eurydice, Alive’s chief leitmotifs, alongside the fatal gaze of the male—the association of pregnancy with death:

On the day they ventured out to sea, it is impossible to say whether my mother was pregnant, and if the movement she felt inside her was new life or the premonition of death. As they waded away from the shore, my mother followed my father deeper and deeper into the cool dark water. Her eyes smiled at him from behind her black mask as she adjusted it once more before dipping beneath the waves, the blues and greens of the world below slowly coming into view.

When Thorne’s mother is then immediately struck and killed by a passing fishing boat, Thorne’s anguished father bears the mangled body of his wife, Orpheus-like, back to shore, and the family’s charismatic religious community prays for their departed member’s life to be restored. The Eurydice theme has now been fully sounded in the author’s own life—with the refinement of this new pair of ill-fated lovers now presented as parents, indeed as potentially pregnant with further issue. And in what follows from this dreadful concatenation of erotic fruitfulness and sudden demise, combined with Thorne’s subsequent motherless upbringing and exposure to the vicissitudes of a patriarchal world, the symbolism of Orpheus’s illicit look is lent its fully death-dealing force as the author must deal with the mixed messages of her religious upbringing: she has been taught to respond to the desiring regards of men with the light of Christ, so as to distract them from her physical form, while preparing herself at the same time for a life of biological service as an obedient wife and mother, all under the distraught but invasive eye of her faith- and grief-addled father.

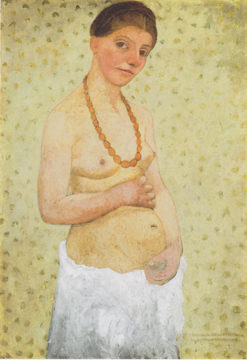

When Thorne subsequently discovers the work of Modersohn-Becker, who took to signing her name simply “PB” after leaving her husband, Otto Modersohn, but felt unwilling to return to her “maiden” name either, the author is impressed both by the promise of the painter’s brief but productively emancipated life as an artist and by the famous “Selbstbildnis am 6. Hochzeitstag” (Self-Portrait at Sixth Wedding Anniversary, 1906). In that painting, Modersohn-Becker depicts herself naked—a premiere in the annals of nude painting, in which the artists had been exclusively male, and female models had never portrayed themselves—; furthermore, the painter also shows herself pregnant, although in fact at the time she was neither together with her husband, nor was she expecting. (In a final irony, Modersohn-Becker would in fact ultimately die from complications due to childbirth at the age of 31, having become actually pregnant not long after completing the self-portrait.)

Paula Modersohn-Becker was thus one of the very first female artists to return the male gaze so forthrightly, and surely the first to direct her artist’s eye at her own, naked form, as well as among the first to deploy pregnancy as a metaphor, standing for the artist’s fruitful fullness with her own creativity, rather than as the naturalistic fact of reproduction, to be borrowed as a symbol by her male colleagues. The German painter initiated a turn in the artistic tradition, as exemplified by Louise Bourgeois’s marvelous late “Pregnant Woman” series (2008), red gouache drawings of female torsos, pregnant, giving birth, and breastfeeding, on view now in a show curated by Jenny Holzer at the Kunstmuseum Basel: the female artist deploys the sign of her own putative corporeal functionality as a rhetorical and figurative gesture.

Thorne, for her part, although not the first female artist to rewrite the story of Orpheus and Eurydice, is in excellent company. Most recently, in the film Portrait de la jeune fille en feu (2019), writer and director Céline Sciamma has her female protagonists elaborate a new reading of the myth, one that restores agency to Eurydice by wondering whether she didn’t in fact herself call for Orpheus to turn and face her, thus becoming the manipulator of the gaze, rather than its object, or indeed victim—a radical revision of the classical power relationship. (And indeed Daniel Graf, in a brilliant essay, uses this very scene in Sciamma’s film to formulate a bold new theory of the role of art in a democracy.) And, in a commissioned modern production this season at the Opernhaus Zürich, Stefan Wirth adds a new work to an operatic tradition that began over five centuries ago with musical dramas based on the classical account of Orpheus and Eurydice by Peri and Monteverdi. Girl with a Pearl Earring, with a libretto by Philip Littell from Tracy Chevalier’s eponymous novel, although not obviously derived from the ancient myth, yet rewrites that story’s inauguration of the fatal and yet productive gaze of the male artist by imagining the collaboration of Vermeer’s female subject with her portraitist, in a transaction that has the object now acting as a subject in her own depiction; and the opera, true to the novel on which it is based, also features that subject’s survival of “her” painter, and her inheritance of some of the requisites of his trade.

Thorne, for her part, although not the first female artist to rewrite the story of Orpheus and Eurydice, is in excellent company. Most recently, in the film Portrait de la jeune fille en feu (2019), writer and director Céline Sciamma has her female protagonists elaborate a new reading of the myth, one that restores agency to Eurydice by wondering whether she didn’t in fact herself call for Orpheus to turn and face her, thus becoming the manipulator of the gaze, rather than its object, or indeed victim—a radical revision of the classical power relationship. (And indeed Daniel Graf, in a brilliant essay, uses this very scene in Sciamma’s film to formulate a bold new theory of the role of art in a democracy.) And, in a commissioned modern production this season at the Opernhaus Zürich, Stefan Wirth adds a new work to an operatic tradition that began over five centuries ago with musical dramas based on the classical account of Orpheus and Eurydice by Peri and Monteverdi. Girl with a Pearl Earring, with a libretto by Philip Littell from Tracy Chevalier’s eponymous novel, although not obviously derived from the ancient myth, yet rewrites that story’s inauguration of the fatal and yet productive gaze of the male artist by imagining the collaboration of Vermeer’s female subject with her portraitist, in a transaction that has the object now acting as a subject in her own depiction; and the opera, true to the novel on which it is based, also features that subject’s survival of “her” painter, and her inheritance of some of the requisites of his trade.

Thorne’s signal contribution to this evolution, meanwhile, is a progressive reappropriation of the trope of virginity, that liminal state privileged in its absence, and only once it has been erased by “successful” motherhood. Having herself feigned pregnancy to ward off the unwelcome male gaze, thus reenacting Modersohn-Becker’s gesture of stylized pregnancy as a symbolic emancipation, both as woman and as artist, Thorne returns, in the final pages of Eurydice, Alive, to a consideration of the “virgin” state in which she had begun, when she read Rilke as a young person “still below the surface of life”. Having suggested, in a fanciful philological excursus, that Eurydice’s name might be etymologized to mean “the wideness of what is”, Thorne bestows a new status upon her resuscitated heroine, and thus upon herself, the burgeoning artist whose own mother retraced the steps of the original, doomed Eurydice:

When Eurydice descends into Hades, she discovers a new virginity, but it is not what I had once imagined upon first reading Rilke beneath the warmth of my duvet. It is no longer a protective measure, or even a holding back, but a complete openness which closes her to anything less than the fullness of reality.

Our final glimpse of Thorne in this narrative is of a young writer enjoying the ecstatic freedom of simply being alive in a self-created reality, celebrating “the wideness of what is” as she struggles with the words that will become this very text while on a visit to Worpswede, where Modersohn-Becker and Westhoff had met and worked alongside one another in an artist’s colony. For our part, we may look forward to the further reality Thorne will bring to term out of such a paradoxically contained openness.