by Michael Liss

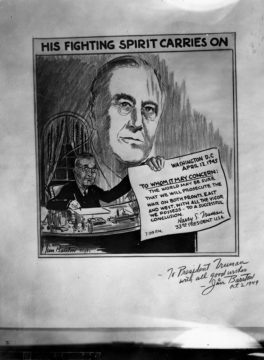

I have a terrific pain in the back of my head.

—Franklin Delano Roosevelt, April 12, 1945.

It was all so fast. Just moments earlier, FDR was sitting for an official portrait, reading the newspapers, writing a few notes. Now, after 12 years of turmoil, World War and Depression, he is gone, work unfinished. Within hours, his successor, Harry S. Truman, is sworn in, and, for the first time, is told of the Manhattan Project. The awesome moral responsibility for the use of nuclear weapons falls on his shoulders, and a bullseye appears on his back.

The fact is that Vice Presidents are pretty much non-entities, supporting actors in a one-man play, unless and until they suddenly become the most important person in the world. History shows us that this occurs far more often than simple mortality tables might suggest. By one estimate, being President is about 27 times more dangerous than being a lumberjack.

The authors of the Constitution understood this, but, after vigorously debating the extent of Executive Power and the interrelationship of the three branches of government, and creating the future monster known as the Electoral College, they flickered out a bit when it came to figuring out Presidential succession beyond the elevation of the VP. Instead, they kicked the can to Congress in Article II, Section 1, Clause 6, to declare which “Officer” would act as President if both the President and Vice President died or were otherwise unavailable to serve during their terms of office “until the disability be removed, or a President shall be elected.” Read more »