by Leanne Ogasawara

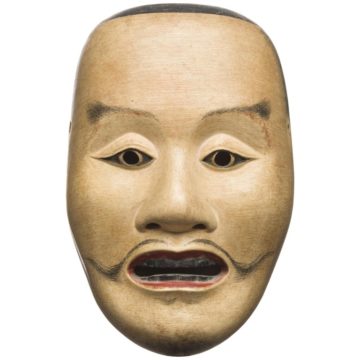

The masked actor walks slowly forward. Pausing, he ever so slightly tilts his head upward. The audience is astonished; for with that tiniest upward tilt of his head, the facial expression of the mask is transformed –and he now appears smiling. How had these mask carvers, now long dead, managed to create these works of art that appear so different depending on the angle they are viewed?

The Noh theater is often cited as being the longest continuously-performed theater tradition in the world—with masks considered to be amongst the finest ever created.

Attending a performance, the first thing you might notice is the way time itself immediately slows down and takes on a stretched-out quality.

You suddenly have time to notice all kinds of things.

Like how long it takes the actor to walk toward center butai stage from the curtain. Several years ago, I worked on a translation on the traditional Japanese walking style, Nanba aruki. Commonly associated with Edo period samurai dramas, the style is to walk with knees slightly more bent and to move the arms as little as possible—But if moved the right arm moves in tandem with the right leg, the opposite of modern styles of walking.

At first, it was surprising to realize that people might not have always have walked like we do now. But some people think this nanba aruki style is healthier since hips and shoulders move together, rather than opposed. Also, I learned that because the center of gravity is lower due to slightly bent knees with feet gliding on the surface, it is an effective way of moving through marshes or other tough terrain.

This is relevant today in Japanese martial arts and the tea ceremony, where we were taught to walk with our hands placed immovable on our thighs (or holding the utensils as carefully as possible without any unnecessary extra movements).

It is also at play in the famous ninja run.

It is also at play in the famous ninja run.

This knees-bent gliding style of walking, called suri-ashi in Noh– is radically slowed down in the performance. Some scholars have speculated that because Noh was influenced by the Shinto that there was god in everything in nature, even the ground was seen as a place where gods reside and therefore the slow and less-impactful sliding walking style was a gesture meant to not awaken these gods.

It must take the actor five full minutes to arrive at the center of the stage—slowly slowly gliding past the three pine trees moving toward the main stage. To the audience it appears “he’s only just walking slowly” but, in fact, the enormous effort to walk in that methodical manner raises his pulse to 170– and as much as up to 207 during particularly challenging walking scenes. Just donning the Noh mask and slowly walking across a short stage raises the actor’s pulse to that of a runner’s.

It’s kind of like walking across a glacier. Macfarlane in his book Mountains of the Mind described the way he would start off going 5 miles, thinking, “Oh, I’ll be on the other side in a few hours… only to be huffing and puffing still walking twelve hour later.”

To appreciate what is going on beneath the surface of that slow walking requires the audience to recalibrate its conception of time.

2.

2.

In my tea lessons, my sensei always encouraged an economy of movement.

“Do what feels most natural,” she would say. And “Try to be minimal.”

It never worked for me. I found I had better luck in my lessons when I did what felt most unnatural –instead of most natural. But that was due to all the preconceived notions I brought with me into the tea room.

My sensei would try to encourage me by saying I was no different from her incoming high-school students, who “also didn’t know how to walk across tatami mats” or “how to open the sliding door.”

It was so complicated, and every time I would be on the cusp of remembering the long set of procedures, the season would change and I would be back to square one. It was impossible for me to memorize anything because of this constant rotation of seasons in the tea room.

In Noriko Morishita’s lovely book, Every Day a Good Day: Fifteen Lessons I Learned about Happiness from Japanese Tea Culture, she talks at some length about how rather than memorizing the uncountable number of seasonal procedures, she only aimed to “be there.” And over the decades to gain a bodily know-how for natural moving and sitting in the tea room. This was something, she said, that could be absorbed over time.

And I suppose that is why I was there.

In tea, I learned to pay attention. Morishita comes to refer to chanoyu in her book, as a “ceremony of attention.” In my lessons, I was trained to notice the sounds of water boiling like “winds in the pines,” shush, shush, shush. Or to pay attention to the poem written on the hanging scroll reflected in the seasonal flowers arranged in the tokonoma.

Lessons seemed to last an eternity as it was the smoldering incense that kept the time.

Nowhere in my life did I experience time dilation like I did during a tea ceremony. Sometimes it was almost as if time itself had stopped completely. This different kind of time has always been something which has deeply attracted me, from the dance dramas in Java to tea ceremony and Noh theater in Japan.

Returning to California, time always feels flat, linear, and mundane.

This modern model of time probably originated in Aristotle’s Physics. In what is basically “clock time,” time is experienced as uniform and discrete “now-points.” It is atomized in the language of philosophers. Homogeneous and transitive, with the past as no-longer-now and the future as something which unfolds from the present moment.

But kind of like how we walk, so pervasive has this notion of time become that it almost sounds silly trying to describe it here. But I think it bears remembering that this is not the only notion of time available to us.

I am reading The Scent of Time: A Philosophical Essay on the Art of Lingering, by Byung-Chul Han and he talks about the way “the medieval calendar did not just serve the purpose of counting days. Rather, it was based on a story in which the festive days represent narrative resting points. They are fixed points within the flow of time, providing narrative bonds so that the time does not simply elapse.”

I am reading The Scent of Time: A Philosophical Essay on the Art of Lingering, by Byung-Chul Han and he talks about the way “the medieval calendar did not just serve the purpose of counting days. Rather, it was based on a story in which the festive days represent narrative resting points. They are fixed points within the flow of time, providing narrative bonds so that the time does not simply elapse.”

He says our current conception of time, which he calls “meagre time,” is a time without scent. It lacks that which endures, that which creates stable bonds across large stretches of time.

Picking up on Heidegger, he makes extensive use of the terms ‘slow’ and ‘slowly’. Of the importance of lingering in order to engage in a life of contemplation, instead of relentless activity that aims to fill time. I have never fully trusted people who constantly tell you how busy they are, which is a kind of Americanism in a way. Haste, franticness, restlessness, nervousness and a diffuse sense of anxiety determine today’s life. Instead of leisurely strolling around, one rushes from one event to another. According to Byung-Chul Han, haste and restlessness characterize our modern time. Frenetically busy and anxious, our focus is becoming more and more scattered.

Anna Sherman, in her wonderful books The Bells of Tokyo, explores Japanese notions of time. She is puzzled, she says that while “English has a single word for ‘time’, Japanese has a myriad.” She learns that some terms reach backward into the ancient literature of China–uto, seisō, kōin. “From Sanskrit,” she says, “Japanese borrowed a vocabulary for vastness, for the eons that stretch out past imagination toward eternity: kō. Sanskrit also lent a word for time’s finest fraction, the setsuna: ‘particle of an instant.’”

And from English, the Japanese took ta-imu. Ta-imu is used for stopwatches and races.

To have so many expressions for different kinds of time hints at richer possibilities for experiencing time.

From Walter Benjamin, I learned that around 1840 in Paris, it was briefly fashionable to take turtles for a walk in the arcades. These turtle walkers were the celebrated flâneurs of the city– and not only did they walk their turtles like the cabbage man of Kashmir walks his cabbages, but the Paris flâneurs always let the turtles set the pace.

Turtle steps, turtle steps…

There was also the poet Gérard de Nerval who had a penchant for lobsters– or at least for one lobster. It was his pet. He became famous for walking his lobster in the gardens of the Palais-Royal in Paris, promenading his crustacean about at the end of a long blue ribbon.

As word of this feat of eccentricity spread, Nerval was challenged to explain himself. To which he said: “I have affection for lobsters. They are tranquil, serious, and they know the secrets of the sea.”

- The Noh Mask 能面

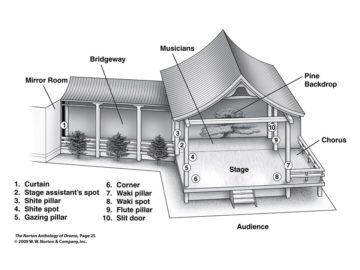

What we call Noh Theater today is an art form codified by actor and philosopher Zeami in the 15th century. However, the roots of Noh stretch much further back in time to the masked dances that traveled up and down the Silk Road and slowly found their way to Japan starting in the 8th century.

The now-extinct masked dance gigagku, for example, which has its origins in Central Asian or Indian dance, was brought to Japan by a Korean dancer as early as 612. (Images of masks here)

In Noh, not everyone on stage wears a mask. In fact, often it is only the principal actor, known as shite. The actor playing the shite aims to suppress his ego as much as possible. At the moment he places the mask on his face his entire personality is extinguished, and the actor becomes possessed by the god or ghost of the play. Spirit resides in the expressionless mask as the actor seeks with all his self to reflect this spirit to the audience.

In Jeffrey Dym (Sacramento State University) fantastic documentary on masks, Noh men – the spirit of noh, he suggests that in the early period, the masks were created as stand-ins for statues of Shinto or Buddhist gods. There is evidence, he says, that the original folk masks were created in the image of the statues so that the deities could come out of the temple and walk around outside. I once read that the tradition of promenading religious statues is relatively rare in the world—with India, Japan, Italy, and Spain being well-known examples.

The extremely slow pace of singing, walking, dancing, and storytelling on stage, enables the audience to detach itself from the ordinary clock-time to enter a type of ceremonial or sacred time, thereby allowing the masks to exert power over the human imagination.

4.

Personal Side-Note on Masks

Personal Side-Note on Masks

I hesitate to bring up philosopher Slavoj Žižek but like Heidegger and Barthes, he has sometimes turned his attention to Japan in order to gain a critical distance to his own preconceived notions:

The usual cliché now is that Japan is the ultimate civilization of shame. What I despise in America is the studio actors’ logic, as if there is something good about self-expression: do not be oppressed, open yourself up, even if you shout and kick the others, everything in order to express and liberate yourself. This is a stupid idea — that behind the mask there is some truth. In Japan, even if something is merely an appearance, politeness is not simply insincere. […] Surfaces do matter. If you disturb the surfaces you may lose a lot more than you accounted for. You shouldn’t play with rituals. Masks are never simply mere masks. Perhaps that’s why Brecht became close to Japan. He also liked this notion that there is nothing really liberating in this typical Western gesture of removing the masks and showing the true face. What you discover is something absolutely disgusting. Let’s maintain the appearances.

I remember when I complained to my Japanese husband after we moved to the countryside that every time I answered the door, the person standing there would pause, mouth falling open before saying, Ah, gaijin da! (A foreigner, heaven forbid!)

“Well, what do you want them to say?” Tetsuya said. Then, after a pause, he continued:

“If you are wearing a police uniform they will respectfully call you omawari-san (police officer) and if you want them to know you are the wife of the house, put your apron on….”

When I recovered from my initial surprise, I tried this out (I didn’t have a police uniform but did have a large collection of aprons) and sure enough, without missing a beat, the visitor would address me in Japanese as okuusan–honorable wife– and we would conduct whatever business had brought them to my doorstep naturally in Japanese. I just had to speak the language and identify myself as belonging in some understandable manner, I supposed.

While at first it was strange and off-putting to be identified by a role (or mask), still there was a simplicity is these things. Don’t you think? For these tasks that we throw ourselves into, in the end, they do have tremendous significance in much the way Zizek suggests. That is to say, because we throw ourselves into these tasks, they are almost always inherently worth doing.

Talking about this once with a scholar of Chinese philosophy, he said

Regarding Zizek’s quote, I guess the “Western” idea that there is an “essence” behind our “superficial” roles owes a lot to Platonic/Christian dualism that is largely absent from Buddhist and Confucian thought.

This is probably true….And sometimes it feels in America that I am in some kind of Danielle Steel novel– as if I only could throw off my many masks I could get to the essence of my true self. And then I come to my senses– and try and enjoy the view from the glacier instead!

5.

Snow in a silver bowl銀梳裏盛雪

Snow in a silver bowl銀梳裏盛雪

Yūgen 幽玄is the word most oft-used in describing Noh.

Part of the group of aesthetic terminology from Japanese that has made itself known in English as part of the self-help industry, like wabi-sabi, “Zen,” kintsugi, ikigai, ichigo-ichie, Yūgen is a word the Japanese themselves use to advertise their culture. This below is from Shiseido:

Yūgen is a word that has no translation in English, but it is a feeling we will all have felt. It has been loosely summed up as “an awareness of the universe that triggers emotional responses too deep and powerful for words”, but has also been called “mysterious grace”, “subtle profundity” and the “beauty of the unseen”.

I have felt myself thinking Yūgen when gazing at the nigh sky from the top of Mauna Kea—as thousands and thousands of stars were visible. It was so vast and profound to really look at the stars lighting up the Milky Way.

I have also felt this when looking into a bowl of tea served in a black raku bowl. The jade color whipped matcha appeared to be sizzling against the darkness. Mysterious and alive, as if there was a dragon in that teabowl.

Words fail as time seems stretched. Whether the ancient light from stars now dimmed or the feeling of falling into a sacred space where the world appears inside a teabowl or a masked actor becomes a long-dead poet or a god.

Zeami said that Noh should be like snow in a silver bowl. For that is Yūgen.

++

Thank you, Sally, for the chat about Zeami!

The other day, I stumbled upon this amazing Youtube video (below) of Rick Emmert performing the Noh play Hagoromo in collaboration with Javanese dancers set to the music of the gamelan. The collaborative dance is so unusual not just because of its Javanese-Japanese collaboration but also it is the Javanese dancers who wear the masks and Rick (the shite) is mask-less. The chanting is classical Javanese court style and yet… I would say it is the noh play that really creates the mood and atmosphere of this.

I only wish I could have been there. For more on Hagoromo, please see my Substack Hagoromo 羽衣 “Doubt is for mortals. In heaven, there is no deceit.” And for more on yugen, my substack Snow in a silver bowl.

Collaboration: bedhaya hagoromo

To read:

- Japan through a Slovenian Looking Glass: Reflections of Media and Politic and Cinema (Slavoj Zizek)

- Every Day a Good Day: Fifteen lessons I learned about happiness from Japanese tea culture, by Noriko Morishita, Eleanor Goldsmith (Translator) Susan Blumberg-Kason’s review here.

- The Scent of Time: A Philosophical Essay on the Art of Lingering, by Byung-Chul Han

- Anna Sherman’s The Bells of Old Tokyo

- My essay on time and the tea ceremony in Entropy Magazine: FOOD AND COVID-19: WIND IN THE PINES

- My essay on time in 3QD CIRCLES IN TIME