[This is the eighteenth in a series of essays, On Climate Truth and Fiction, in which I raise questions about environmental distress, the human experience, and storytelling. All the articles in this series can be read here.]

Early in the story of The Walking Dead — the enormously popular, post-apocalyptic, television series — sharpshooting everyman, Rick Grimes, finds himself cast as leader to a group of beleaguered survivors, who must navigate the malignant chaos of a world suddenly overtaken by zombies. Every comfort, convenience, and civic structure of modern American life has collapsed. The threat of death lurks beyond every hillock or behind any tree. Ordinary people are left to fend for themselves against overwhelming forces, with nothing but guns (and the odd pickaxe or crossbow) for aid. And sentimental attachments to other people only leave individuals more vulnerable to attack. In this world that has slipped the grip of civilization, Grimes works to keep a strain of justice and mercy aloft within his desperate band.

Early in the story of The Walking Dead — the enormously popular, post-apocalyptic, television series — sharpshooting everyman, Rick Grimes, finds himself cast as leader to a group of beleaguered survivors, who must navigate the malignant chaos of a world suddenly overtaken by zombies. Every comfort, convenience, and civic structure of modern American life has collapsed. The threat of death lurks beyond every hillock or behind any tree. Ordinary people are left to fend for themselves against overwhelming forces, with nothing but guns (and the odd pickaxe or crossbow) for aid. And sentimental attachments to other people only leave individuals more vulnerable to attack. In this world that has slipped the grip of civilization, Grimes works to keep a strain of justice and mercy aloft within his desperate band.

But torn away from the cogency of his ordinary, 21st-century life, and cast into unrelenting danger and uncertainty, even Grimes’s kinder impulses are slowly ground away by his unabating experiences of horror and loss. His moral compass spins erratically. By the fifth season of The Walking Dead, the line separating Grimes from the threats he’s fought for years to hold at bay has worn distressingly thin. In fact, much before this, the show’s storylines and characters have already notably shifted their attention from the horrors of the zombies to the horrors of relying upon one’s fellow dislocated human beings for refuge and assistance in an ongoing crisis. Confronting the atrocities committed by the living profoundly changes Grimes and every member of his crew, as they also become more adept killers. Yet, uncannily, the social world they inhabit together doesn’t change much at all.1

New narratives or mythologies grasping for new understandings of their changed environment, moral quandaries, or identities have not begun to emerge. None among them bothers much about making a reliable living or teaching the children or searching for meaning. Oddly, they remain wholly fixated upon their enemies and armaments. Seemingly lacking in dreams, imaginative hunger, or pragmatic creativity, they don’t begin to re-conceive society in ways that take shape in collaboration with whomever and whatever is left. They remain, throughout, an eternally ragtag cadre of survivalists hoping or despairing for the world only as it was, rather than as they might make it.

American zombie tales regularly feature this functional collapse of modern civilization and the subsequent slide of civil society into relentlessly violent confrontation. Visions of our post-collapse future as a battlefield of all against all, with storylines centering questions of individual survival, leadership, moral rectitude, or heroism seem increasingly common. In fact, preoccupation with these themes isn’t limited to worlds beset by zombies; it’s widely shared across contemporary post-apocalyptic stories, all of which seem to be growing in popularity. I’m not the first to suspect that the rise in the appeal of these tropes might reflect a genuine cultural anxiety about the potential collapse of our present global civilization.

Civilizational collapse is not an easy thing to imagine; it asks us to extend ourselves beyond almost our entire known world. Still, it bears asking what leads so many storytellers to presume that without modern, Western-hegemonic civilization there can be no civilization—only chaos and barbarity. American writers, in particular, apparently find it difficult to conjure a post-collapse future where guns aren’t the most important tool, ammunition isn’t magically limitless, and killing the enemy (or even one’s allies) isn’t a person’s primary occupation on an ordinary day.2 Consider hit films of the past decade—The Quiet Place, Bird Box, The Road, Mad Max, and others—in which humanity has been beset by aliens or plague or some other, often unspecified, civilization-ending event. On some level, these stories seem to say, forget the zombies/aliens/plague/unnamed agents of catastrophe—for we are the monsters; without modern civilization to contain and police us, all is brutality and Hobbesian terror. Removed from modern conveniences and state structures, it seems, we readily slide back to some brutish primordial state.

Perhaps these stories are our modern-day answer to Grimms’ fairy tales, projections of our collective cultural nightmare—in our case, of losing control of Nature and ourselves in it, of witnessing the dissolution of our “social contract.” Such nightmares, grounded in underlying worldviews that our humanity is separate from and superior to Nature, can keep us holding onto the folly that the present civilization must be continued at any cost—especially if that cost is “merely” a future for the least empowered among us—for beyond it lies the lethal wilderness of our inner dragons. But such Lord of the Flies assessments of the human material that keep surfacing are unimaginatively ethnocentric. And if we fear the collapse of modern civilization, it’s worthwhile to understand what collapse could actually mean, beyond the unexamined projections of our worst nightmares.

What Actually Happens When Societies Collapse

While we fictionally imagine apocalypse, collapse has become a loaded term in serious discussions about the future of our capitalist-consumerist global civilization. As the possibility of collapse begins to feel more vivid to many of us, others more stringently deny its relevance as a historical process. Thus the Rapanui civilization didn’t collapse; the Roman Empire, the Mayan states, the early Mesopotamian states didn’t collapse. It’s not as if all those people simply died, we’re reminded, or that nothing of their culture survived to be inherited by later societies. They merely faded and morphed into something new. So there’s no such thing as civilizational collapse, only decline.

But, like most things, collapse isn’t usefully understood as a binary or static concept. Studies of the collapse of complex societies—those with larger populations that are socially and economically diversified and stratified, yet politically integrated through centralizing institutions, as in kingdoms, nations, or empires—reveal that not every case is identical in magnitude or effect; much depends on the proximate triggers, the sociocultural substrate, the environmental context, and how people respond. Nor does collapse occur evenly across all parts of a society. It produces random and unexpected outcomes, pockets of resilience and novel social adaptations. It’s a process that typically plays out over decades, even if one can identify a swift, triggering incident. For example, the catastrophic explosion of a nearby volcano dealt a sudden and devastating blow to the ancient Minoans of Crete, covering much of their island with ash and inundating it with a disastrous tsunami. But the consequent collapse of Minoan civilization occurred over the following generation or two, ultimately fading behind the concomitant rise of Mycenaean arrivistes from the Greek mainland, who took advantage of the Minoans’ weakened condition to impose their own power and displace the Minoans on Crete.

But, like most things, collapse isn’t usefully understood as a binary or static concept. Studies of the collapse of complex societies—those with larger populations that are socially and economically diversified and stratified, yet politically integrated through centralizing institutions, as in kingdoms, nations, or empires—reveal that not every case is identical in magnitude or effect; much depends on the proximate triggers, the sociocultural substrate, the environmental context, and how people respond. Nor does collapse occur evenly across all parts of a society. It produces random and unexpected outcomes, pockets of resilience and novel social adaptations. It’s a process that typically plays out over decades, even if one can identify a swift, triggering incident. For example, the catastrophic explosion of a nearby volcano dealt a sudden and devastating blow to the ancient Minoans of Crete, covering much of their island with ash and inundating it with a disastrous tsunami. But the consequent collapse of Minoan civilization occurred over the following generation or two, ultimately fading behind the concomitant rise of Mycenaean arrivistes from the Greek mainland, who took advantage of the Minoans’ weakened condition to impose their own power and displace the Minoans on Crete.

While the collapse of any society isn’t uniform or instantaneous, it does occur over a shorter timeframe than the rise of that society to its peak. By that yardstick, collapse is relatively abrupt, in contrast to a decline. When complex societies collapse, centralized power devolves to more regionalized power. Elites loose significant wealth and status; sometimes they’re completely felled, their lineages dissipating into oblivion. Monumental works cease; official levers of power and communication wither; economic diversity shrinks. Patterns of residence may shift dramatically, due to some combination of mass migration and mass death. Stories are lost, even whole languages or writing systems. These periods are sometimes identified as “dark ages” or “intermediate periods” of history. But what this characterization misses is the subaltern vantage—for what those at the center of empire experience as collapse, those at the peripheries may experience more as liberation. As much as stories die out, new ones also arise. So that, in fact, when we look at historical examples of collapse, we see that despite the severe difficulties such episodes create for many people, they can’t be simplified as a time of unmitigated horrors the way our popular myths would have it.

Classist Ellen Morris describes, for example, the collapse that ensued in Ancient Egypt, when a spate of great floods along the Nile River caused prolonged and widespread famines, toppling the pharaohs of the Old Kingdom. With centralizing authority gone, lesser elites up and down the Nile valley vied with each other for power.3 Cities and small settlements across the shattered empire had to rely upon their immediate neighbors for aid and sustenance. Local militias, bandits, criminals, and foreign raiders terrorized people in the streets and in their fields. Cemeteries filled up faster than before, due to violence as much as famine. Yet cities, towns, and villages did carry on. Despite the trenchant hunger and degrees of mayhem, people were busily figuring out new ways to get by as smaller, but still functioning, societies. Some non-elite families, relieved of empire’s heavy tax burden, now had more spending power and could compete for status previously denied them. The former nobility, reduced to relative penury, bemoaned the fact that servants now wore precious stones and spoke unabashedly to their superiors. New styles proliferated in clothing, ceramics, writing, religious and artistic expression. Social hierarchies weren’t totally leveled but the old structures of power were challenged and changed—in ways that proved both good and bad for individuals and ultimately changed their stories, reshaping their future expectations of monarchy.

Perhaps an even greater remixing of status was experienced in pre-Classical Greece, when the world of the Mycenaean warlords crumbled into the Aegean Dark Age. According to archaeologist Ian Morris, massive population shifts occurred as urban settlements shrank and some regions of Greece were entirely abandoned.4 Those who tilled the land and tended the herds of the great Mycenaean palaces decamped, coalescing into myriad tiny hamlets, more locally self-reliant yet still productively farming and plying some trades, without the yoke of their former masters. Of course, though the warlords had fallen, violence continued to stalk the Peloponnese in new permutations. But the previously stark social distinctions of wealth and rank faded from the burials of their dead. And even as the Greeks’ collective memory of the Mycenaean period morphed into legends of heroes and battles and odysseys, over the next five-hundred years, it also seeded strands of cultural resistance to tyranny. Perhaps it’s this that would later flower in Athenian experiments with democracy.

So while history shows that the collapse of complex societies results in a breakdown of law and order and the disruption of official trade networks and markets, leading to increased privation and hardship for many, we don’t see the wholesale annihilation of any and all civic or community structures, such as we’re given to imagine in our apocalyptic fantasies. Functional social organization doesn’t require centralized authority. It doesn’t depend upon sophisticated scientific knowledge or plumbing or energy grids. When such things are taken away, we’re not cut morally adrift to devolve into the beasts of our zombie-apocalypse nightmares. Rather, in the midst of the ensuing uncertainties, we reinvent functioning social worlds within our changed circumstances. Social identities shift, or dissolve and reconstitute anew. Vestiges of traditions mapping older or regionally based ways of life, social structures, and institutions may also emerge to become foundations for new sociopolitical or economic organization. Wherever civic structures can still be found—whether through resilient local governance, materially supportive bonds of kinship, trade networks, political alliances, or something else—these may serve as nodes for maintaining selective cultural continuity, cohesion, and sustenance. Such a dynamic is observed in Lebanon today, in the wake of that country’s devastating economic collapse.

Indeed, as journalist Rebecca Solnit reminds us in A Paradise Built in Hell, in times of acute crisis, there are at least as many people pulling together as are pulling apart. Resourceful people organize and lead. Those most severely affected by crisis seem to lean toward cooperation, sharing their energy and pooling their resources, broadly awakening a palpable spirit of pro-sociality. And while there are always problematically selfish or “antisocial” individuals among us, most societies don’t preferentially reward sociopaths with leadership roles (as ours does), nor does the challenge they present necessitate a wholesale devolution to mutually antagonistic bands, as our popular myths suggest. Human societies—particularly non-state societies—have always found stories that normalize sharing and social cohesion, permit broad personal autonomy, and provide strategies for reckoning with with antisocial individuals. I imagine that even suburbanites-turned-foragers wandering the zombie-infested, American countryside of our apocalyptic imaginings would begin to re-discover how. It is absolutely essential to acknowledge this likelihood—without the zombies—even to foreground it. For if barbarity is the only post-collapse future we can imagine, then it’s the one we’ll aim to fashion—building bunkers, stockpiling weapons, hoarding food, fixating on enemies and armaments—whether we wish to or not. For we can only ever reach toward that which we first imagine; never what we don’t.

In short, collapse need not be conceived as an End of History nor reduced to a story of unmitigated human depravity. In the words of anthropologist Joseph Tainter,

“What may be a catastrophe to administrators (and later observers) need not be to the bulk of the population. It may only be among those members of a society who have neither the opportunity nor the ability to produce primary food resources that the collapse of administrative hierarchies is a clear disaster. Among those less specialized, severing the ties that link local groups to a regional entity is often attractive. Collapse then is not intrinsically a catastrophe. It is a rational, economizing process that may well benefit much of the population.”5

Notably, those lacking the ability to produce food includes primarily the urban poor—hundreds of millions of people today. Collapse leaves too many people vulnerable to starvation, crime, dislocation, war, and social disorientation. Of course, all of these things are already experienced in our world today. And while, in a collapse scenario, these disasters would surely begin to afflict a wider cross-section of people, anthropologist Norman Yoffee observes that both collapse and any subsequent societal regeneration are modes of change that can ultimately be understood in terms of familiar social dynamics.6 That is: despite the disruptions, societies remain recognizable as societies. The key, I think, is to understand the collapse of complex societies as rapid social change—or transition—toward simplification or more localized, smaller-scale societies, rather than as the end of society or the void of civil humanity that many of us learn to imagine through our contemporary fables.

Collapse leads to social transformation; how that plays out depends on the conditions and context of the collapse. So, while collapse is the end of a world, it’s not usually the end of the world.

The Looming Collapse

What—apart from zombies and alien invasions—causes complex societies to collapse? In Tainter’s analysis, collapse is an economic adjustment that results from the growing costs associated with growing social and technological complexity—eventually, the civilizational bubble bursts.7 Environmental and systems’ scientist Donatella Meadows instructs us that, in fact, any complex system growing exponentially will eventually collapse; no simple intervention can prevent it.8 At best, a properly timed series of systemic corrections might hope to achieve a managed decline and equilibration, rather than more precipitous collapse. Centralizing complexity is ultimately a self-limiting phenomenon. History bears this out, given that every complex society ever built has fallen.

What—apart from zombies and alien invasions—causes complex societies to collapse? In Tainter’s analysis, collapse is an economic adjustment that results from the growing costs associated with growing social and technological complexity—eventually, the civilizational bubble bursts.7 Environmental and systems’ scientist Donatella Meadows instructs us that, in fact, any complex system growing exponentially will eventually collapse; no simple intervention can prevent it.8 At best, a properly timed series of systemic corrections might hope to achieve a managed decline and equilibration, rather than more precipitous collapse. Centralizing complexity is ultimately a self-limiting phenomenon. History bears this out, given that every complex society ever built has fallen.

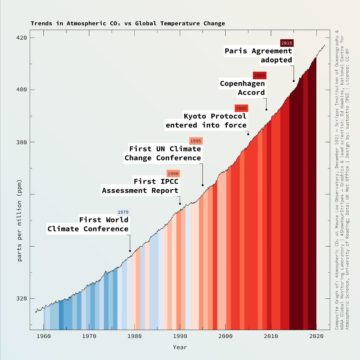

So what does this mean for our modern world? After all, we live in an exponentially growing, complex society. Today, the challenges and costs of managing urban and industrial pollution, mitigating global warming, recovering from the catastrophes of our changing climate, maintaining agricultural productivity in an eroding biosphere, and battling pandemic continue to mount every year and will only increase more steeply into the future—just as models of complex systems predict. The present trend of rising costs and continued growth is quite plausibly approaching its inflection point. And though we’re constantly reminded that “it’s not too late” to stop global warming with solar panels and windmills, there’s little to suggest that we’ve not already missed our window for the dramatic actions necessary to manage a humane degrowth of the global economy, an equitable and systematic reduction of overall energy use and consumption, that might slow collapse into decline and equilibration.

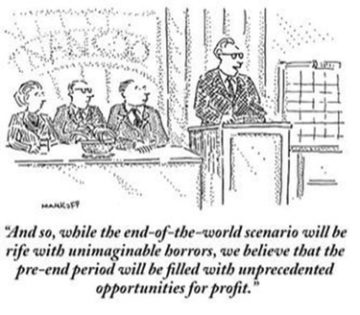

Nor are the necessary actions even now being genuinely considered. Regrettably, this very fact illustrates the several, interrelated social, cultural, and psychological dynamics that allow complex societies to collapse, rather than engineer a gentler decline. For one, politically influential elites are buffered from the damages of environmental overshoot until it’s too late to effectively respond. After all, they’re not among the species going extinct. They aren’t even breathing the foul air or drinking the poisoned water near the refineries and mines. They aren’t collapsing in farm fields under the rising heat, going hungry due to drought or flood, working longer hours to catch fewer fish, splashing and spraying greater amounts of noxious chemicals to grow the same quantity of grain, or sending their children deeper underground to dig up more cobalt. Unaffected by the fundament crumbling away far beneath them, not only do the elites do nothing to prevent collapse, they may actually work to prevent its potential remedies—because the remedies, of course, include dispossessing them of their disproportionate wealth.

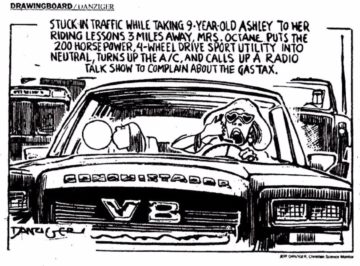

But non-elites enable collapse too. They too want what the elites have, after all; they want what the present system is known to provide. And for all of us—elites and non-elites alike—the experience of past abundance or predictability biases us, or lulls us, into the expectation of future abundance or stability. This kind of ignorance or denial, sometimes shading into willful blindness, keeps individuals engrossed in the dominant illusion factory—religion, pop culture, media circus, propaganda, or whatever carries the day—encouraging them to not look up, as it were, and to disregard the actual trajectory of the larger system in which they live, even as it palpably tips toward collapse. Of course, civilizational restructuring is always difficult once a society gets locked into a particular track of development. All of its material and sociocultural infrastructure then carry it farther along the rails it builds as it goes. And the more complex a society, the more tightly its members are bound up within its self-referential realities, the more blithely they continue to lay the tracks in the same direction. All of this creates a material barrier to the adoption of new paradigms or possibilities of thought and behavior. As stresses mount, people who are persuaded society is on the right track will double-down on their present beliefs and practices in the expectation that these are what will solve society’s problems, even when these are the very source of those problems.

But non-elites enable collapse too. They too want what the elites have, after all; they want what the present system is known to provide. And for all of us—elites and non-elites alike—the experience of past abundance or predictability biases us, or lulls us, into the expectation of future abundance or stability. This kind of ignorance or denial, sometimes shading into willful blindness, keeps individuals engrossed in the dominant illusion factory—religion, pop culture, media circus, propaganda, or whatever carries the day—encouraging them to not look up, as it were, and to disregard the actual trajectory of the larger system in which they live, even as it palpably tips toward collapse. Of course, civilizational restructuring is always difficult once a society gets locked into a particular track of development. All of its material and sociocultural infrastructure then carry it farther along the rails it builds as it goes. And the more complex a society, the more tightly its members are bound up within its self-referential realities, the more blithely they continue to lay the tracks in the same direction. All of this creates a material barrier to the adoption of new paradigms or possibilities of thought and behavior. As stresses mount, people who are persuaded society is on the right track will double-down on their present beliefs and practices in the expectation that these are what will solve society’s problems, even when these are the very source of those problems.

The climate and the biosphere are perhaps the two most fundamental systems upon which our civilization is inalienably dependent. Today, the biosphere is collapsing in what may prove to be the Sixth Great Mass Extinction event, caused by humans having annihilated habitats, obliterated non-human populations, and distributed unimaginably vast quantities of poison and waste across the planet. At the same time, our climate has been wildly destabilized by the rapid injection of greenhouse gases, resulting from humans having made sweeping and destructive changes to the Earth’s land- and seascapes and having burned great lakes’ and mountains’ worth of fossil fuels. As collapsologists Pablo Servigne and Raphaël Stevens timidly sum it up, considering our ecological and social limits, as well as the dynamics of complex systems,

“Today, we are sure of four things: (1) the physical growth of our societies will come to a halt in the near future; (2) we have irreversibly damaged the entire Earth system (at least on the geological scale of human beings); (3) we are moving towards a very unstable, ‘non-linear’ future, where major disruptions (internal and external) will be the norm; and (4) we are now potentially subject to global systemic collapses.”9

The looming collapse, upon whose precipice all of humanity presently stands, promises to be of a greater magnitude and deeper consequence than any previous civilizational collapse. Its potency results from its ecological overshoot having exceeded that of any past society, as well as its planetary scope. Such a monumental degree of potential collapse can perhaps only proceed from a society of exceptional complexity, like our own, maintained through unprecedented flows of energy and materials supplied by centuries of accelerating environmental degradation, which have eroded the carrying capacity of the planet. This extreme degree of ecological overshoot has only been achieved through the installment of layers upon layers of technology and social hierarchy working in tandem to delay the consequences of overexploitation and overgrowth, allowing us to most efficiently steal the planet’s future productivity for short-term gain, while simultaneously separating the high-living, decision-making minority from the realities of the land and lives that sustain them.

The looming collapse, upon whose precipice all of humanity presently stands, promises to be of a greater magnitude and deeper consequence than any previous civilizational collapse. Its potency results from its ecological overshoot having exceeded that of any past society, as well as its planetary scope. Such a monumental degree of potential collapse can perhaps only proceed from a society of exceptional complexity, like our own, maintained through unprecedented flows of energy and materials supplied by centuries of accelerating environmental degradation, which have eroded the carrying capacity of the planet. This extreme degree of ecological overshoot has only been achieved through the installment of layers upon layers of technology and social hierarchy working in tandem to delay the consequences of overexploitation and overgrowth, allowing us to most efficiently steal the planet’s future productivity for short-term gain, while simultaneously separating the high-living, decision-making minority from the realities of the land and lives that sustain them.

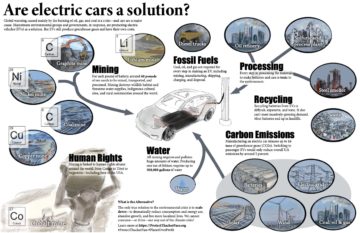

New technologies have proliferated to address the mounting problems created by the previous technologies—yet without ever adequately addressing the root problems of overpollution and overexploitation. Social and economic tiers have mounted to facilitate the rising complexity of all the complex subsystems of extraction, production, distribution, consumption, and technology creation, to do all the increasing amounts of work and wastage that keep it afloat. These hierarchies are further reinforced by our system’s rewards for greater efficiency of hoarding, control, and domination of people and planet. And such extraordinary layers of Earth-alienating technology and socioeconomic hierarchy have only been possible due to the unique fund of concentrated energy that came to us in the form of fossil fuels.

But now the living world is exhausted. Pollution builds up. Cheap fuel runs low—and isn’t being replaced nearly fast enough by any alternative, nor can it be without further accelerating overexploitation and overpollution. The layers of technology and society are stretched and squeezed beyond their limits to facilitate more and more and more. Collapse seems inevitable. The open questions are when, how, and what follows in its wake?

Collapse and Regeneration

So we are left with this painfully unwelcome but eminently likely future. How will it feel? How do we navigate it? How might we mitigate it? Many of us are grappling with such questions, lacking sufficiently cogent, honest, and humane narratives to help us look beyond the breach. For those who feel anxious or despairing, I believe it’s important to acknowledge what our gut is telling us. Not to acknowledge our fright and despair prevents us from changing our paradigms. And if we can’t change our paradigms, our choices will only reproduce and extend the problem, rather than allow us to discover new paths. Yet each of us, in our own lives, in the lives of our communities and our shared world, must prepare to discover something new.

Of course, if complex societies always eventually fail, we might ask, how does it matter what we do today? It matters because the dynamics and results of collapse are neither binary nor static. It matters because the conditions of the disintegration determine so much of what’s possible both during and afterward. How we receive refugees today and into the near future will set the conditions for how things break down, how much suffering prevails, how well community regrouping and reinvention can proceed or new narratives find purchase. What we choose to create, inherit, and carry forward to navigate the calamity could help to cushion (or worsen) the fall for many. Multiple correct interventions might yet even steer us some meaningful bit closer toward decline than collapse. Helpful initiatives include mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions; forays into transformative agriculture and regenerative farming; exploring alternative farmable food sources, vegetarian aquaculture or polyculture, and more localized food production; reductions of private-car transport infrastructure in favor of pedestrian, cyclist, and mass-transit services; reducing consumption of goods and energy through recycling and downscaling. If such projects are designed and undertaken as part of an overall strategy for degrowth—which, regrettably, excludes perhaps most of the initiatives presently underway—they could help to reign in some degree of global warming, feed and house more people awhile longer, save more living species and maintain more pillars of ecosystem integrity.

Of course, if complex societies always eventually fail, we might ask, how does it matter what we do today? It matters because the dynamics and results of collapse are neither binary nor static. It matters because the conditions of the disintegration determine so much of what’s possible both during and afterward. How we receive refugees today and into the near future will set the conditions for how things break down, how much suffering prevails, how well community regrouping and reinvention can proceed or new narratives find purchase. What we choose to create, inherit, and carry forward to navigate the calamity could help to cushion (or worsen) the fall for many. Multiple correct interventions might yet even steer us some meaningful bit closer toward decline than collapse. Helpful initiatives include mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions; forays into transformative agriculture and regenerative farming; exploring alternative farmable food sources, vegetarian aquaculture or polyculture, and more localized food production; reductions of private-car transport infrastructure in favor of pedestrian, cyclist, and mass-transit services; reducing consumption of goods and energy through recycling and downscaling. If such projects are designed and undertaken as part of an overall strategy for degrowth—which, regrettably, excludes perhaps most of the initiatives presently underway—they could help to reign in some degree of global warming, feed and house more people awhile longer, save more living species and maintain more pillars of ecosystem integrity.

And every bit of wilderness and biodiversity we can still preserve intact and unpoisoned, every fraction of a degree we can forestall from global heating will allow the biosphere to stabilize and regenerate that much faster. Adapting to the future Earth will surely prove challenging enough for many of today’s species, including our own, but it needn’t be reduced to the worst possible case. Whatever seeds of community and however much awareness of ecologically sensitive practices we’re able to plant today may become nodes of resilience in an uncertain tomorrow. If today we begin to genuinely reflect upon what is worth carrying forward, we might move in more promising directions. Voluntarily accepting degrowth of the human enterprise, in exchange for its resilience and continuance alongside the non-human world we cherish—and need—requires a profound change in how we see our place in the world and what we expect from it. It requires nothing less than social and personal transformation. But fighting against what the privileged among us would experience as civilizational decline will likely only lead us to choices that make the impacts of collapse much worse for all.

We are on the cusp of the end of a world. But not necessarily at the end of the world. For if we are able to imagine it, something new might yet be made.

****

“Complex societies, it must be emphasized again, are recent in human history. Collapse then is not a fall to some primordial chaos, but a return to the normal human condition of lower complexity.”10 —Joseph A. Tainter

[Part 19: What We Talk About When We Talk About the Future. All essays in this series can be read here.]

Notes:

1 The social world of The Walking Dead characters doesn’t change much at least up through season 5, a few years into its storyline. That was as much as I could stomach of zombie gore and the constant fighting, in the absence of much else. But the series goes on for well over a hundred television episodes and webisodes, plus multiple spin-off series, continuing in the same vein, as far as I can tell.

2 A notable exception to this trope can be seen in the zombie apocalypse film, Cargo (Netflix, 2018). Perhaps because this film is set in Australia and features Australian Aboriginal characters, who have their own way of understanding and dealing with both the zombies and the apocalypse, it offers a completely different approach to the situation. Another example of alternative, post-apocalyptic storytelling is Snowpiercer (the ongoing Netflix series, not the film), in which the apocalypse is caused by a climate geoengineering project gone wrong. While the characters do frequently fight and vie for power (and viewers must forgive some major plot holes), the story centers on the microcosm of their functioning society of survivors as they try to imagine and make a better world.

3 “Lo, Nobles Lament, the Poor Rejoice”: State Formation in the Wake of Social Flux, by Ellen Morris. In After Collapse: The Regeneration of Complex Societies, edited by Glenn M Schwartz and John J Nichols. The University of Arizona Press, 2006.

4 The Collapse and Regeneration of Complex Society in Greece, 1500–500 bc, by Ian Morris. In After Collapse: The Regeneration of Complex Societies, edited by Glenn M Schwartz and John J Nichols. The University of Arizona Press, 2006.

5 Page 266, The Collapse of Complex Societies (New Studies in Archaeology) by Joseph A. Tainter. Cambridge University Press, 1998.

6 Notes on Regeneration, by Norman Yoffee. In After Collapse: The Regeneration of Complex Societies, edited by Glenn M Schwartz and John J Nichols. The University of Arizona Press, 2006.

7 The Collapse of Complex Societies (New Studies in Archaeology) by Joseph A. Tainter. Cambridge University Press, 1998.

8 Thinking in Systems: A Primer by Donella H. Meadows. Chelsea Green Publishing, 2008.

9 Page 89. How Everything Can Collapse: A Manual for Our Times by Pablo Servigne and Raphaël Stevens Translated by Andrew Brown. Polity Press, 2020.

10 Page 485, The Collapse of Complex Societies (New Studies in Archaeology) by Joseph A. Tainter. Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Images

- Apocalypse-chic. The designers, Yanko Design, claim “This jacket designed to survive an apocalypse is made of the same material used to coat an Apollo mission spacecraft.” Screenshot of Yanko Design website. Fair use.

- A partially reconstructed room in the ancient Minoan Palace of Knossos on the island of Crete. The palace was in use between approximately 1700–1400 BCE. The archaeologist who guided the reconstruction in the 1920s took liberties, so it’s not clear how well this represents the original look of the palace, but there’s no doubt the palace was very large and extraordinarily grand for its day. Image by Usha Alexander.

- Disconnected and entitled elites. Image by Mankoff.

- Disconnected and entitled semi-elites. Image by Danziger.

- Chart showing the rise in the concentration of atmospheric carbon dioxide (in parts per million) since 1960 and how the rate of accumulation has changed in response to agreements made at the major international climate summits. To change the slope of this curve requires the economy to shrink. If that doesn’t happen in a managed program of degrowth, it will happen through civilizational collapse. Image by Ed Hawkins, U of Reading. Creative Commons.

- Chart showing the the environmental costs of producing electric cars. Image by Protect Thacker Pass. Creative Commons.