by David Kordahl

Note: This piece is an accidental addendum to my column of March 2021, “The Limits of Conspiracy Debunking,” though it can be read separately.

Sometimes, we’re surprised. Though everyday surprises can be comedic, the surprises that we register collectively are more often tragic. My parents both remember the assassination of John F. Kennedy as one of the most shocking events of their childhoods. I suppose the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on September 11, 2001, constitute the most shocking of mine. Both the JFK assassination and the 9/11 attacks have attracted conspiracy speculation ever since they occurred. And there are good reasons for this, I contend, even if no conspiracies were involved.

Collective feelings of surprise, of widespread shock, reflect a vague feeling that such events were unlikely, though their very unlikeliness makes their odds hard to calculate. In such cases, alternative explanations—“conspiracy theories,” if you’re feeling ungenerous—seem attractive because they change our estimated likelihoods for surprising events. After these events, it’s natural enough to ask, Why didn’t I see that coming? We might consider, with some shame, whether our expectations should have included wider possibilities, so we might have been less surprised.

After such shocks, the prophets who forewarned disaster gain legitimacy. People retrospectively consider alternatives that accommodate their prior surprise. This rethinking serves to change their subjective odds for the likelihood of the original event. But that’s a problem, if we’re interested in any sort of self-consistency, since this retrospective modulation of odds is only reasonable if we actually should not have been surprised.

This may all sound circular, but there’s a solution at hand. If unique events can be reclassified as non-unique, we can move away from seeing events as being unprecedented, and statistics will once again apply. Returning to shocking events, JFK might be rolled into the category of “political assassinations,” and 9/11 into the category of “political terrorism,” and we might then think through the odds by examining trends in those categories. Read more »

The perfect, so the saying goes, is the enemy of the good. Don’t deny yourself real progress by refusing to compromise. Be realistic. Pragmatic. Patient. Don’t waste resources and energy on lofty but ultimately unobtainable goals, no matter how noble they might be; that will only lead to frustration, and worse, hold us all back from the smaller victories we can actually achieve.

The perfect, so the saying goes, is the enemy of the good. Don’t deny yourself real progress by refusing to compromise. Be realistic. Pragmatic. Patient. Don’t waste resources and energy on lofty but ultimately unobtainable goals, no matter how noble they might be; that will only lead to frustration, and worse, hold us all back from the smaller victories we can actually achieve. My eyes traced the 1500-mile-long arc of the Aleutian Range. Running down the Alaskan Peninsula, the land on either side of the mountains is mainly wilderness and wildlife refuges. Even more astonishing was the complete absence of roads. As a Californian that is hard to fathom.

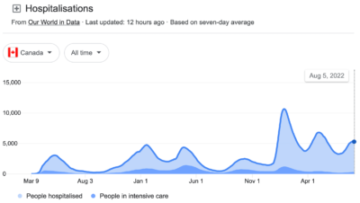

My eyes traced the 1500-mile-long arc of the Aleutian Range. Running down the Alaskan Peninsula, the land on either side of the mountains is mainly wilderness and wildlife refuges. Even more astonishing was the complete absence of roads. As a Californian that is hard to fathom. A mandate isn’t necessarily tyrannical. It’s a rule that, in any good government, is devised to protect the people from harm so we can better live and work together. We must monitor legislation to ensure we stop laws that can harm people, but we also need to get involved when harm comes from a

A mandate isn’t necessarily tyrannical. It’s a rule that, in any good government, is devised to protect the people from harm so we can better live and work together. We must monitor legislation to ensure we stop laws that can harm people, but we also need to get involved when harm comes from a

It’s 1980, I’ve just had my first proper kiss, and the newspapers are announcing the death of love.

It’s 1980, I’ve just had my first proper kiss, and the newspapers are announcing the death of love.

In 1998 when Amartya Sen got the Nobel Prize it was a big event for us development economists. Even though the Prize was announced primarily for his contributions to social choice theory (in particular, his exploration of the conditions that permit aggregation of individual preferences into collective decisions in a way that is consistent with individual rights), the Prize Committee also referred to his work on famines and the welfare of the poorest people in developing countries. Even this fractional recognition of his work on economic development came after a long neglect of development economics in the mainstream of economics. The only other development economist recipients of the Prize had been Arthur Lewis and Ted Schultz simultaneously decades back.

In 1998 when Amartya Sen got the Nobel Prize it was a big event for us development economists. Even though the Prize was announced primarily for his contributions to social choice theory (in particular, his exploration of the conditions that permit aggregation of individual preferences into collective decisions in a way that is consistent with individual rights), the Prize Committee also referred to his work on famines and the welfare of the poorest people in developing countries. Even this fractional recognition of his work on economic development came after a long neglect of development economics in the mainstream of economics. The only other development economist recipients of the Prize had been Arthur Lewis and Ted Schultz simultaneously decades back. In June 1945, the American military appointed twenty-nine-year old Pat Lochridge mayor of Berchtesgaden, the tiny fairytale Bavarian town near the Austrian border crowded by Alps, where three thousand feet up, Hitler built his Eagle’s Nest retreat. “It is the intention of the Allies that the German people be given the opportunity to prepare for the eventual reconstruction of their life on a democratic and peaceful basis,” wrote the Allies at Potsdam.

In June 1945, the American military appointed twenty-nine-year old Pat Lochridge mayor of Berchtesgaden, the tiny fairytale Bavarian town near the Austrian border crowded by Alps, where three thousand feet up, Hitler built his Eagle’s Nest retreat. “It is the intention of the Allies that the German people be given the opportunity to prepare for the eventual reconstruction of their life on a democratic and peaceful basis,” wrote the Allies at Potsdam.  Physicists writing books for the public have faced a longstanding challenge. Either they can write purely popular accounts that explain physics through metaphors and pop culture analogies but then risk oversimplifying key concepts, or they can get into a great deal of technical detail and risk making the book opaque to most readers without specialized training. All scientists face this challenge, but for physicists it’s particularly acute because of the mathematical nature of their field. Especially if you want to explain the two towering achievements of physics, quantum mechanics and general relativity, you can’t really get away from the math. It seems that physicists are stuck between a rock and a hard place: include math and, as the popular belief goes, every equation risks cutting their readership by half or, exclude math and deprive readers of a deeper understanding. The big question for a physicist who wants to communicate the great ideas of physics to a lay audience without entirely skipping the technical detail thus is, is there a middle ground?

Physicists writing books for the public have faced a longstanding challenge. Either they can write purely popular accounts that explain physics through metaphors and pop culture analogies but then risk oversimplifying key concepts, or they can get into a great deal of technical detail and risk making the book opaque to most readers without specialized training. All scientists face this challenge, but for physicists it’s particularly acute because of the mathematical nature of their field. Especially if you want to explain the two towering achievements of physics, quantum mechanics and general relativity, you can’t really get away from the math. It seems that physicists are stuck between a rock and a hard place: include math and, as the popular belief goes, every equation risks cutting their readership by half or, exclude math and deprive readers of a deeper understanding. The big question for a physicist who wants to communicate the great ideas of physics to a lay audience without entirely skipping the technical detail thus is, is there a middle ground? Sughra Raza. Self-portrait in Reflected Morning Light, August 2, 2022.

Sughra Raza. Self-portrait in Reflected Morning Light, August 2, 2022.

If philosophy is not only an academic, theoretical discipline but a way of life, as many Ancient Greek and Roman philosophers thought, one way of evaluating a philosophy is in terms of the kind of life it entails.

If philosophy is not only an academic, theoretical discipline but a way of life, as many Ancient Greek and Roman philosophers thought, one way of evaluating a philosophy is in terms of the kind of life it entails.