by Rafaël Newman

More poetry, my response to loss.

John Weir

It’s 1980, I’ve just had my first proper kiss, and the newspapers are announcing the death of love.

It’s 1980, I’ve just had my first proper kiss, and the newspapers are announcing the death of love.

Well, not quite. But that’s how it would come to feel in retrospect: amid all the rumors, the myths, the half-truths, the superstitions, the warnings. The awful, racist, homophobic “jokes”. The abrupt, unheralded appearance in “family” media of discussions of practices previously not even acknowledged, let alone written about. The grainy, horror-film portrait of the deceased Québécois flight attendant said to be “Patient Zero,” stylized a Typhoid Mary for our times by the tabloids (all due, of course, as much to a misreading as to a witch hunt: the “0” noted in statistics, when Gaëtan Dugas’s infection was reported by the CDC, would eventually turn out to have been an “O”, for “out of state”). And then the wasting. And the protests. And the deaths. And the funerals.

It was during this same period, in the early 1980s, that John Weir arrived in Manhattan, from rural New Jersey by way of Kenyon College, to spend the next decade and a half (for starters, before eventually moving to Brooklyn, where he now lives) in one of the world’s great centers of gay life and culture, soon to become one of the world’s great centers of gay death and resistance. Weir was to live through those first terrible years of AIDS himself, and in 1989 he published The Irreversible Decline of Eddie Socket, an almost unbearably light-hearted account of the vicissitudes of a young man in New York during this period, and of his eventual death of the syndrome; it won the 1990 Lambda Literary Award for Best Gay Debut Novel. In 2006 there followed What I Did Wrong, a roman à clef recounting the demise of Weir’s best friend, the “semifamous gay author” David Feinberg, afflicted by the same illness, and the repercussions in the protagonist’s later life of his agonizing, transfiguring death. Both books have recently been re-issued by Fordham University Press, in recognition of their germinal status as contemporary literature and as records of a period in the recent past whose repercussions we are still feeling (on which more later).

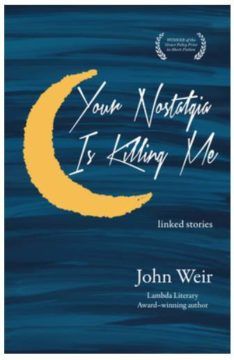

Weir’s latest work, published this year and the winner of the Grace Paley Prize in Short Fiction, is Your Nostalgia Is Killing Me, “linked stories” written between 1997 and 2020 in “East Village; Montrose; Hell’s Kitchen; Flushing; Fishtown; & Gowanus” (as a postscript informs the reader, with a nod to Joyce’s itinerary during the writing of Ulysses). AIDS is as central to the new collection as to the novels—sections have titles like “AIDS Nostalgia” and “Long-Term Survivors”—but Weir also revisits his searingly awful schooldays in the 1970s, tainted by brutal homophobia, and crafts vignettes of his relationship with his formidable mother, and of his life as a now middle-aged gay man in a present-day New York in which people are living with HIV (or dying of it, but only because they “went off their meds….People who were lucky enough to get AIDS meds nonetheless sometimes stopped taking them. Because they were depressed. Because they were isolated and alone. Because they were bored, because they were broke, because they hadn’t planned to still be here by now.”) The new book is thus a continuation of a project of literary activism embarked upon in the late 1980s—a participant observer’s response to an ongoing crisis, his distress, grief, and anger (as well as his spot-on acerbic humor) mediated through an artist’s sensibility—and is in this sense indeed an artifact both literary and political.

Of course, the outbreak of AIDS and its horrific consequences for his own community, among others, and in particular the sluggish, indifferent initial response by political authorities, have moved Weir to more straightforward activism as well, with such groups as ACT UP and Queer Nation, and in the drive to boycott the 2014 Winter Olympics in Moscow by publicly pouring Russian vodka down the drain. One action in which Weir was involved lives on in the virtual world. On January 22, 1991, during “Operation Desert Storm,” Weir and fellow protesters interrupted Dan Rather on the CBS Evening News by dashing in front of the cameras and chanting “Fight AIDS, not Arabs” for a few seconds before their arrest, an intervention that earned him, alongside heroic notoriety, the stern reproof of his television executive father.

Weir is to this day also an engaged chronicler of (and resourceful intervener in) contemporary US politics, on social media, particularly Facebook; indeed, the new book is dedicated to “5,000 Facebook friends and 3,011 followers, at last count”. (Full disclosure: I am one of these.) And it is on that platform that he has recently lamented the reception of his new collection exclusively as “historical document,” even as he acknowledges and underscores its function as a record of political protest alongside its significance as a work of literature: although the book’s intended political function is in part, paradoxically, to protest against the sentimentalization of AIDS in retrospect. “Funny that I had a hard time getting mainstream hetero attention when my first novel was published in 1989, funny that now, 30+ years later, I have a hard time getting mainstream homo attention”: because of his age, he remarks wistfully; but also

…because my book, which covers a time period from 1975 to 2015, more or less, and which spends a lot of time in the 1970s (high school! alas!) and the 1990s (AIDS! alas! ‘Just when you thought nothing could be worse than high school. . .’): the book’s being read as, you know, ‘historical document,’ which…

And just to say—and I mean, read it however you want—but: part of the point of the book is to intervene against the treatment of the first 15 years of the Global AIDS Crisis, 1981 to 1996, roughly, as a Theme Park—‘AIDS World!’ —that we can duck into from time to time when we want to know what it was like Back in the Day.

Sure, I want to show what some people’s lives were like in 1992. One of the book’s impulses, though, is to show how the homophobic culture that permeated and disfigured US life for more than a century: is still disfiguring lives. In spite of ‘It Gets Better.’ In some ways, because of ‘It Gets Better.’ There has always been a cause/effect relationship between ‘acceptance of homosexuality and gender non-conformity’ and ‘violent state-mandated reaction against homosexuality and gender non-conformity.’ We are certainly seeing this now, and not just in Florida.

But here’s the thing: seems to me that AIDS nearly always overwhelms anything else in a narrative. I think there is still so much stigma around AIDS, that if you drop it into a book, it cancels whatever else is happening. Certainly that was true in 1989—I realized, writing my first novel, that I couldn’t write about AIDS without making it central to the story. But that was when hardly anyone was writing about AIDS—and you all know the history of media and government and medical neglect of AIDS.

Now, though, it seems to me—other writers may have a different experience!—that if you write about the first 15 years of the Global AIDS Crisis, you’re condemning yourself to being treated as ‘particular,’ not ‘universal.’ You’re a souvenir. You’re quaint. Argh, I loathe the notion that a story needs to be ‘universal’ in order to appeal to the widest possible readership! ‘This story is about a dying fag, but it has universal appeal!’ Said no one. And anyway, why does a story need to be ‘universal?’

Isn’t the requirement that a story have ‘universal’ appeal a way of saying that it needs to feel like it’s about cisgenderstraightwhitepeople? The ‘universal’ thing is sexist racist ableist homophobic, etc., no? It’s used by critics and book review editors to excuse them from reading anything that is outside their immediate personal experience.

A book has sentences in it. Sentences matter! They carry content, yes, but there are a lot of different ways of saying a thing, and I’m always surprised when readers let content distract them from what’s going on at the level of style.

Yes, why indeed does a story need to be “universal”? Apart from the fact that The Iliad, the wellspring of Western “universal” narrative, is itself a “story about a dying fag” (pace Foucault), surely it is in fact the plausibly particular nature of a literary account—the way it offers me, the reader, access to a reality not my immediate own—that renders it valuable as narrative. That and, of course, its style, which is inseparable from its content or plot: because, as Weir maintains, “Sentences matter!”

And he should know, since he is by his own account susceptible to the hypnotic appeal of certain sentences (he has confessed to being “addicted” to those of Joan Didion) as well as himself the crafter of some dazzling examples. Here he is, in “It Gets Worse,” the final story in the collection and his response to the current happy-clappy bromide, retrospectively responding to the vicious taunting at the center of a circle of his sixth-grade classmates with a meditation on the etymology of his own name, and of the epithets (“faggot,” “fay,” “queer”) hurled at him:

Wyrd is Old English for ‘destiny’ or ‘fate’; and faie is Middle English for ‘fairy,’ or ‘fay’ or ‘fey,’ from the Old English faege, meaning ‘fated to die soon.’ A ‘faggot’ is a bundle of sticks thrown on a pyre to burn witches, and ‘faggoting’ is a decorator’s term for something you do with lace. ‘Queer’ is Germanic, from the root thwerh-, meaning ‘twisted,’ and the Old Norse thverr, which means ‘to thwart.’

So I’m twisted, thwarted and thwarting, fairy-like but fateful, not just silly but lethal, not just deadly but fated to die, kindling for fire, powerful and burning, but also inconsequential, dainty as threads pulled tight around delicate lace. And I’m the star.

Here he is in that same story, conjuring up the “American pastoral” of his boyhood home in northwestern New Jersey with an unflinching eye for the beauty of the ordinary that owes as much to Philip Larkin as to Philip Roth:

Up-thrusting sawtooth solitary stone walls of crumbling churches. A burned-down house and its outbuildings, horse barns and hay barns, charred, vacant, filled with dog turds and trash from the 1950s. Clogged ponds in cement beds. Railroad tracks that run to the Musconetcong River but don’t cross it, stone pylons for their vanished trestles looming over the river bank. Abandoned cars in open fields, ’57 Chevys with shattered windshields and spring rotting seats. Dead bodies of gutted deer left behind by hunters, poachers. Private family cemeteries up in the woods, overgrown with weeds and trees, big rocks for headstones. Rock walls lining fields that have long since returned to forest, dogwood, skunk cabbage, walking fern, shadbush, pitcher plants that drown bugs, rain-soaked mossy logs, poison ivy, poison oak.

And here he is, in the volume’s penultimate, eponymous “linked story,” one of two recounting his haunted love affair with a beautiful, difficult man living with HIV, recalling the first decade and a half of AIDS, that period now in danger of fossilization as “AIDS World!”:

The agony of that age, twenty-five years ago. The crisis we lived through, at the same time, in the same city. Shit smears on white sheets, bones in sight under skin. The litany of weird diseases only birds got. The trauma of that time.

Here, in all of these passages, is true poetry, in the midst of despair at human folly and perversity, and of grief at the loss of life, and of love. And indeed, for all of his political engagement, Weir’s is not the discursive “objectivity” of the Joan Didion he reveres, what Hilton Als, citing Didion herself on Hemingway, calls her “way of looking but not joining”; for Weir’s irony is too vivid, his commitment to the literary too strong, his lyricism too present for the dispassion of New Journalism.

And yet, in these lyrical stories, Weir is certainly also given to direct socio-political commentary. Consider his identification, in response to a lover’s history of abuse at the hands of men, of an epidemic of “masculinity in America” accompanying the epidemic of HIV. Consider his complex analysis of the fear, indeed hatred of men that subtends a contemporary gay culture obsessed with hyper-masculinity, and contemptuous of any sign of softness—of femininity!—in the male body: and of how this toxic neurosis among gay men grows, paradoxically, out of the constant, ineradicable misogyny that is always also a part of “straight” homophobia, and about which Weir has written explicitly in his Facebook posts. Consider his account of the group rituals of heterosexual hazing, of the abuse poured on the “effeminate” boy by his prospectively “straight” peers, for whom “faggot” is a “safe word”: an analysis of the function of the insult in the shaping of the male psychology every bit as theoretically sophisticated as are the sociological constructs of Didier Eribon. And finally, consider Weir’s unstinting analysis of the way that he himself has internalized this pathology, whereby the homo-social, and indeed the phallocratic, coexists with a murderous hatred of men who have sex with men: as he writes in “Kid A,” a melancholy and soulful meditation on the dangerous loneliness of American masculinity, “I’m gay because I hate, not women, but men. I’m terrified of men, which means that I can’t resist them. I want to know how it feels to be a man. I don’t want to touch them, I want to be them.” (Here he is echoing the bitter formulation of his own 1980s protagonist, Eddie Socket, who identifies the bad faith at the heart of corporate, homophobic, misogynistic America: “…it’s okay to like dicks… It’s America. Everyone in America is supposed to like dicks, as long as it sells the product. Just don’t take your dicks with your legs up over your head.”) “Kid A” ends as the “camera” pans away from the porn cinema in Queens where the narrator has just had an assignation with Rico, a stranger, in a “buddy booth,” to take in the environs and to elaborate a joyfully pessimistic position on the American project:

And if I could have talked to Rico, I would have said, with guy-like sentimentality, not embarrassed, “Man, I love New York.” Wreckage and disaster. I love looking at this intersection of highways and trains and planes taking off overhead and cars crashed and the river stagnant below and thinking, This is all we can do, this is the best we can ever do; we get off the boat from faraway places and build across the new land a redeemer nation of what? Sewage, slop, waste, rot, rusted steel, the gaping awful failure of a century. Face-to-face with man’s capacity for wonder, and we make ourselves, in Flushing, a mess.

Here, prefaced by an acknowledgement that this very region of New York is the setting for a pivotal scene in The Great Gatsby, Weir renders explicit the terrible lesson of Fitzgerald’s account of American self-making for our present day, the way that the “Great American novel” is the record of both a dream and a nightmare.

Ultimately, for all of its urgent reflections on contemporary socio-politics, Your Nostalgia Is Killing Me is a work of literature: a work steeped, furthermore, in the Anglo-American literary tradition. Weir is an associate professor of English and creative writing at CUNY and an assiduous and eclectic reader, and he manages the Ninja-level feat of combining an occasionally telegraphic colloquial tone (“Which: fine.”) with serious literary erudition, to produce a realism that is also intensely allusive and intertextual. (There is a fine joke in “Kid A” about students hearing a “rumor” that their instructor is “intertextual” and petitioning him to offer a course in postmodernism: the narrator wonders whether the rumor isn’t true, as he scribbles poems for a young man with whom he is besotted on the last page of a book by Roland Barthes.) The authors who serve as Weir’s literary touchpoints eventually become familiar to the habituated reader: Didion, of course, alongside Auden, Blake, Crane, Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Yeats… There is a risk to this style, of course, although Weir virtually always sticks his landing. Perhaps the sole not entirely successful story in the collection, “Katherine Mansfield,” about a doomed bicoastal love affair between an impoverished New Yorker and a wealthy music star in LA, suffers from a surfeit of literary references, beginning with the irony of the title and continuing through a series of snappy but faintly condescending jokes by a Mandarin at the expense of a vapid pop culture; indeed, the main story threatens to engulf the secondary narrative, a wistful account of straight/gay misunderstanding less encumbered by allusion, which however emerges to overtake the primary story and make of it a frame narrative for its more affecting content.

And of course, at the “meta” level, Weir has always been aware of this risk. Eddie Socket, the eponymous hero of Weir’s first novel whose biography borrows selectively from his creator’s, has a habit of reciting apposite snippets of verse, prose, and Broadway lyrics, and then asking his (usually irritated) interlocutor, “Who am I quoting?” (For the record, Weir is demonstrably aware of the proper accusative inflection of the interrogative pronoun; his commitment to vernacular verisimilitude simply outweighs grammar.) Eddie is in this sense the ancestor of the author of “Katherine Mansfield,” flaunting rather than harnessing his erudition. But in the final paragraph of the final chapter of The Irreversible Decline, entitled “The Art of Losing,” in the aftermath of Eddie’s death, the narrator’s voice takes over, in anticipation of the more seasoned and restrained protagonists of the new stories, and performs a fully earned, extended, un-“referenced,” heart-wrenching allusion to Elizabeth Bishop’s celebrated 1976 villanelle, “One Art,” which begins:

The art of losing isn’t hard to master;

so many things seem filled with the intent

to be lost that their loss is no disaster.

and continues, resolute in the face of a terrible grief, which is unspoken but can be sensed in the choked sob of its final, parenthetical imperative:

—Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture

I love) I shan’t have lied. It’s evident

the art of losing’s not too hard to master

though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster.

In Your Nostalgia Is Killing Me, Weir is still attempting to master this art, which is perhaps “not too hard,” but doesn’t come overnight either. His preferred method is writing, and poetry; the problem is, as he reveals in the two linked stories about his lover Scott, writing about a person is also a way to lose them; and “I don’t want to lose people anymore, even if only in writing.” After decades spent consoling and caring for dying friends and lovers, he despairs at his inability to do any more than simply be by their side, loving them.

But after all, what can we lay persons do but this? The medical response continues. The most recent International AIDS Conference, held in Montreal, brought news of encouraging progress in treating HIV, although of course Sub-Saharan Africa lags behind the rest of the world, along with other regions in which stigma prevents groups at risk from seeking help, and members of the “general” population fear association with those groups. Meanwhile, the current response to monkey pox may well be encountering the specter of the same bigoted resistance that slowed the initial treatment of AIDS. As for the rest of us, we can continue to protest, and to raise funds, and to contribute, and to write, even if that last activity may mean losing the ones we love a second time. Because remember: the choice isn’t to “love one another or die,” the imperative is to “love one another and die.” (Who am I quoting?)

Because: love and death. What else is there in life?

In memory of Robert Tobin (1961—2022)