by Marie Snyder

A mandate isn’t necessarily tyrannical. It’s a rule that, in any good government, is devised to protect the people from harm so we can better live and work together. We must monitor legislation to ensure we stop laws that can harm people, but we also need to get involved when harm comes from a lack of legislation. A good mandate is put in place when harm can be prevented in an enforceable way. For instance, despite the fact that skin cancer costs many lives each year, and suntan lotion can prevent these deaths, using suntan lotion isn’t mandated. It would be nearly impossible to enforce its use. Seatbelts, on the other hand, have been mandated for decades. In the states, traffic collisions take about six times as many lives as skin cancer*, so seatbelts potentially save more lives than sun lotion. They’re also much more easily noticeable and enforceable.

A mandate isn’t necessarily tyrannical. It’s a rule that, in any good government, is devised to protect the people from harm so we can better live and work together. We must monitor legislation to ensure we stop laws that can harm people, but we also need to get involved when harm comes from a lack of legislation. A good mandate is put in place when harm can be prevented in an enforceable way. For instance, despite the fact that skin cancer costs many lives each year, and suntan lotion can prevent these deaths, using suntan lotion isn’t mandated. It would be nearly impossible to enforce its use. Seatbelts, on the other hand, have been mandated for decades. In the states, traffic collisions take about six times as many lives as skin cancer*, so seatbelts potentially save more lives than sun lotion. They’re also much more easily noticeable and enforceable.

I was just 11 years old, when I was first forced by my mum to strap myself to a car with a 2″ vinyl band with metal clips that held me tight against the seat. It felt like wearing a straight jacket, and I protested the infringement on my freedom. I wasn’t the only one; in many places “resistance was the norm” to seatbelt laws. Mum was avoiding fines of $240 from our Conservative Premier Bill Davis (about $1,200 now), and she was further cajoled by ads on TV showing the aftermath of people thrown from a car. Children weren’t kept from these gruesome images, sometimes shown at school assemblies. Such was the level of care we could expect back in the 1970s.

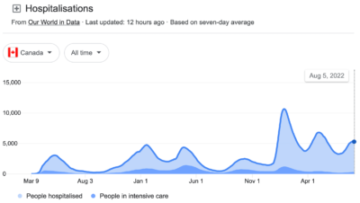

Kids today are being similarly traumatized, it’s suggested, as they’re made to feel suffocated by polypropylene or silicone masks that can cause sweating and sometimes acne. Well, they were, but now they’re free to breathe the unfiltered air in buildings everywhere in many countries despite the elevated chance of someone nearby carrying an infectious disease, which, in some areas, kills more than ten times as many people as car accidents.* Covid hasn’t finished with us. In Canada, recent hospitalization valleys are higher than previous peaks!

While we’re very aware of the potential for ongoing trauma and disability from a traffic accident, Covid discussions often ignore the people who survive but are forever impacted by the disease, experiencing chronic “LongCovid” symptoms months later. That affects 20% or 30% of Covid cases, some previously mild or asymptomatic. We’re lacking the government-funded PSAs that educated us all on dangers on the road, particularly people for whose experience with a mild case has convinced them it’s all overblown. It’s interesting we don’t see that dismissiveness from people lucky to walk away unharmed from a car crash.

Disturbing images of collisions lodge in our minds (see this old ad for a mild version, and this montage for some news footage), and memorable slogans were easily repeated by parents and friends:

- “There are a million and one excuses for not wearing seatbelts. Some are real killers.”

- “Even dummies wear seatbelts”

- “Click it or ticket.”

- “Buckle up for safety!”

They featured analogies that stick: an accident at 100 kph is like falling from a 10 story building. Or they depicted the tragic aftermath with a paralyzed teenager openly ostracized by his old friends, showing teens how much they’ll miss out on if they’re not careful.

We wouldn’t think of putting our children in a car without a seatbelt in place. But in many countries, we’re convinced it’s safe to have them in schools without a mask, allowing them to catch consecutive cases despite repeated infections doubling the risk for death, blood clots, and lung damage, and tripling the risk of ending up in the ICU. Why were masks such a fleeting tool despite N95s being so effective at preventing transmission** of this virus and further vaccine-evasive mutations?

Years after seatbelts laws, as a new mum I was pleased with anti-smoking legislation that restricted smoking to part of restaurants, until I realized that decision to try to appease both smokers and non-smokers realistically did little to keep my baby from inhaling smoke from a neighbouring table. It took another step to completely ban smoking in restaurants and other public spaces so people were able to avoid breathing in toxins while they ate. There’s always dissent on big issues, but it’s the government’s place to stand firm in protecting citizens with laws around seatbelts, smoking, gun control, and, hopefully, climate change. But Covid doesn’t give us the luxury of time to try to please everybody before finally reimposing mandates.

Earlier in the pandemic we all saw tragic footage of people intubated, their family members in tears outside the hospital saying goodbyes over the phone. Ongoing reminders of the reality of Covid might be all that can alter our behaviour: vignettes that show how LongCovid can affect us like Alzheimer’s, or involve debilitating pain enough to provoke people toward suicide, or show a healthy teen being spoon fed, no longer able to perform basic activities in this “living death,” with familiar slogans: “Wear a mask: the life you save may be your own.”

The analogy between seatbelts and masks falls short, though, because seatbelts mainly save our own lives, and wearing a mask can reduce the chance of others getting Covid. We need to be reminded of the 31% of Omicron cases that are completely asymptomatic. It spreads well because it’s sneaky! Smoking is a better analogy to wearing a mask might, as is drunk driving, since they both affect others. The current rhetoric in my area is that wearing a mask or not wearing one are equally valid choices, but that’s like saying driving drunk or sober are equal choices even though one clearly has a much greater potential to cause harm. Australia’s PSAs on drunk driving are clear and to the point: “If you drink then drive, you’re a bloody idiot.”

We could be so bold, except there’s an unspoken impression that we aren’t supposed to question anyone’s judgment about masking in indoor public places. Worse, in some cases the message implies a non-mask default, like this event’s messaging: “Be respectful of each other’s choices. There are all sorts of reasons that people would want to wear a mask.” As this Slate article explains, “One-way masking is being proposed as a sufficient alternative to universal masking for immunocompromised. This adds a scientific veneer of legitimacy to lifting mask mandates at a time when U.S. COVID numbers are still far too high and more than 2,000 people are dying daily.” Imagine the difference if this was the dominant message instead: “Remember that viruses are in the air and masks can protect us. We’re much more protected as more of us wear them. Show you care with a mask!” People hated seatbelts but eventually caught on, preventing less than a tenth of the destruction to life and livelihood currently being caused by Covid. Why the grave difference with masks? We know that Covid harms children despite shifting from “schools are safe” to “getting it is inevitable” in the blink of an eye. In my neck of the woods, face coverings that are worn by medical professionals all day and habitually by children in many countries, raise concerns far surpassing any worry of getting or spreading a highly contagious fatal or disabling virus.

Some suggest the rise of individualism and competitiveness has made us care less about our effect on others. The more sensitive in the lot experience moral injury affected by the pain from a collective madness. The world feels crazy in its callousness as we’re asked to accept more and more people choosing not to wear masks despite the potential harm to others in the room. Taking precautions that affect society are seen as a lifestyle choice that must be tolerated. Principles of inclusion are vital for things we can’t control, but we cross a line when we demand acceptance for harmful behaviours that are easily manageable. As assistant professor of art Maggie Mills wrote recently, “Death and suffering have been normalized to such a horrific extent that the vulnerable are now expected to remain ‘civil’ when asking not to be disposed of so that others can keep social plans intact. The moral vacuum of the current moment is shocking.” The notion of living with it by ignoring it is rhetoric devoid of any plan that glorifies individualism to keep us from finding strength in collectivism.

Removing mask mandates is ableist and ageist in nature, asking us to accept greater risks and less public accessibility for a third of people who have some type of underlying condition and for those over 60, rather than be mildly inconvenienced. In the 1980s and 90s rules changed to make buildings more accessible. Equal access became a necessity, not just a perk. Now we have policies that actively prevent people at risk from accessing grocery stores, pharmacies, libraries, arenas, schools, and universities. Instead of legislating cleaner air and mandating masks, we’re supposed to assess our own risk without concern for the risk we bring to others and without any tracking of cases to make personal assessment remotely feasible. This also neglects to recognize the disability caused by Covid, which will create an even greater need for accessibility in future. We accept that it’s a public responsibility to clean water, monitor food safety, and devise traffic rules. We accept limitations around driving drunk. So it’s curious that we’ve shifted responsibility to individuals to choose to mask in order to protect themselves and others. We’ve removed a very simple and effective protection from a growing danger.

Why would leaders do anything to reduce the likelihood of people masking? Have we really just stopped caring about one another? Here are some other possibilities:

Illusion of Control: When things are too scary, we convince ourselves that, if we just don’t do that one thing, then we’ll be safe. It’s similar to victim blaming when we insist that a sexual assault happened because of clothing choice. We’ve very quick to say ‘not it,’ labelling monkeypox a gay disease when it’s been shown to be airborne and affecting children. People are struggling to avoid acknowledging the hazards, but the virus isn’t as frightening if we take measures to prevent transmission.

Keeping the Peace: We’re being placated. Without masks, then we can’t trace the spread, and then it’s nobody’s fault. We stopped any concerns with finger pointing or guilt from infecting others by removing all masks to prevent the possibility of tracing it back to us when a baby gets sick or a teenager has to drop out of school because they can’t get out of bed. We stopped the potential guilt from not masking instead of stopping the virus. But masks are a clear sign of adherence to one side or another in a growing divisiveness which can also affect the peace, and mandates can reduce divisiveness by preventing this overt identifier of allegiances if we all have to wear one.

Symbolism of Disease: Masks make the situation palpable when we’d like to forget it. They remind us we need to be on guard when we’d rather relax. The mask is a symbol of vulnerability; people who openly prevent catching it are painted as fearful, and some are embarrassed to get Covid or are shocked to be asked to test before coming over as if they couldn’t possibly be diseased. These associations need a dramatic reframing as it’s the virus that’s the problem, and masks are the solution.

Avoid Liability: If masks are a personal choice instead of mandated, then catching the virus is on you, not on your employer. It’s far less costly to businesses and governments if we’re told to buy our own masks, if we like, instead of changing building codes to ensure better ventilation and adding masks to employee safety standards, requiring someone to ensure compliance or else face a lawsuit. But this should be treated no differently than any other safety standard. Leaders should be shamed for skirting responsibility for protecting citizens.

Profits: In the short term, removing masks seems antithetical to boosting the economy when it’s adversely affected by excessive absences and But, most abhorrent, long-term, allowing health care and education sectors to collapse might be the first step in a privatization scheme. In 1982, Milton Friedman advised, “Only a crisis–actual or perceived–produces real change. When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around” (xiii-xiv). And then he helped usher in the neoliberal free market policies by promoting predatory ideas that put more money in the pockets of the few rather than humane ideas that promote the health and well-being of the many. This very real crisis fell into the hands of far-right governments and donors who can allow it to decimate public services until we’re begging to pay for private options from companies owned by them or their friends and family. Many have been convinced that masks somehow cause learning loss and mental health issues, when disruption to learning happens when we don’t have safe schools, and mental health problems in youth are directly tied to the rate of Covid cases. How have we bought into the ridiculous idea that wearing a mask could be more detrimental in schools than experiencing rotating illnesses in classes, permanent disabilities, and the loss of loved ones?

As more and more people experience deaths or know someone who suffered a severe illness or who are managing a chronic case, the more difficult it will be to keep people operating in denial of the scope of this situation or under the illusion that it’s over. The only way to slow the spread of a disease with so many asymptomatic carriers is to stop the virus at the source with mask mandates. I don’t think we’ve lost the capacity for empathy, but we are being led down a path that encourages us to allow harm instead of provoking us to act against it. We need to return to collectivist communities, recognize our own agency, rewrite the narrative driving anti-mask rhetoric, and curtail the insidious move towards privatizing public services that put profits over people.

Masks save lives. Masks show you care. Strap one on for safety!

______

* I used American stats, but my province of Ontario has very similar ratios albeit with far fewer numbers. American fatalities in 2021: 7,180 from skin cancer; 42,915 from traffic collisions (more than any year since 2005), and 462,414 from Covid.

** Studies showing that masks are effective in reducing transmission: BMJ, Applied Physical Sciences, Science, Swiss Medical Weekly, JAMA, Science, Applied Physical Sciences, PLOS ONE, Brookhaven National Laboratory, and CDC. Studies showing that mask mandates more effectively reduce transmission: CBC, BMJ, Infectious Diseases, Ontario Public Health, American Family Physician, Health Affairs, PNAS, JAMA, and CDC.