by TJ Price

F-1: blueprint

The house, then, and its rooms. Viewed from the outside, it is nothing extraordinary: situated at the top of a hill, its single-level structure is unassuming. The front lawn is studded with the acorns of oaks and maples, themselves with none of their lowest branches reachable from the ground. There is a small flower garden in the center, ringed with stones yanked from the surrounding woods like teeth, and the façade of the house is guarded by unkempt rhododendrons even on the brittlest of winter days. The long driveway bristles with forsythia on one side, golden and inviting in the early spring.

It is not a place I visit anymore, except for in memory and in dream, both of which are unreliable navigators, though I imagine it cannot help that the map I’ve given them is outdated. When I left the house and its rooms for the last time, I did not know I would not be returning, otherwise I would have taken more careful note of its territory.

A house has multiple forms of ingress and egress, though only some are doors. This house had a front door—rarely used, except for Halloween trick-or-treat (and even then, only a handful of times before we started leaving the porch light off)—a back door, which was reached via a small porch, and a sliding-glass door through which was the kitchen, gained access to by means of a deck. There are more doors than there are rooms in the house, but there are more windows than doors, and some rooms have neither. The most common entry-point, however, was through the garage, past the stairs to the cellar, and into the kitchen.

The garage also held a secret door: a mouth which was heralded only by its dangling, uvula-like pullcord. Once tugged, out unfolded a set of creaky, hinged steps, leading up to a squarish hole in the ceiling. This, the attic, whose floor was more like a ribcage, spanned with planks that sprouted off in either direction from the main beam. Between them billowed pink, filamentous clouds of fiberglass insulation. I remember thinking the first time I saw up into that space how visceral it seemed, and from a very young age internalized the image, believing my own chest—and perhaps that attic of my own body, the skull—to be crammed with the same stuffing. Besides that, there wasn’t much in the attic. It was a hollow space, fit only for adventurous rodents and the odd avian inhabitant. Perhaps it is thematically appropriate that the place hovering over all of our heads for so long—the skull of our house’s body—was largely empty. Read more »

The Hanle Dark Sky Reserve is a spectacular spot in Ladakh, in the north of India. It’s surrounded by snow-capped mountains, and at 14000 feet, it’s well above the treeline. So the mountains and the surroundings are utterly barren. Yet that barrenness seems only to enhance the beauty of the Reserve.

The Hanle Dark Sky Reserve is a spectacular spot in Ladakh, in the north of India. It’s surrounded by snow-capped mountains, and at 14000 feet, it’s well above the treeline. So the mountains and the surroundings are utterly barren. Yet that barrenness seems only to enhance the beauty of the Reserve.

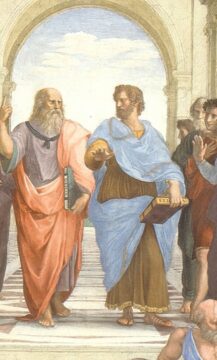

A bit of information is common knowledge among a group of people if all parties know it, know that the others know it, know that the others know they know it, and so on. It is much more than “mutual knowledge,” which requires only that the parties know a particular bit of information, not that they be aware of others’ knowledge of it. This distinction between mutual and common knowledge has a long philosophical history and has long been well-understood by gossips and inside traders. In modern times the notion of common knowledge has been formalized by David Lewis, Robert Aumann, and others in various ways and its relevance to everyday life has been explored, most recently by Steven Pinker in his book When Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows.

A bit of information is common knowledge among a group of people if all parties know it, know that the others know it, know that the others know they know it, and so on. It is much more than “mutual knowledge,” which requires only that the parties know a particular bit of information, not that they be aware of others’ knowledge of it. This distinction between mutual and common knowledge has a long philosophical history and has long been well-understood by gossips and inside traders. In modern times the notion of common knowledge has been formalized by David Lewis, Robert Aumann, and others in various ways and its relevance to everyday life has been explored, most recently by Steven Pinker in his book When Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows.

Sughra Raza. Departure. December 2024.

Sughra Raza. Departure. December 2024.

In recent years chatbots powered by large language models have been slowing moving to the pulpit. Tools like

In recent years chatbots powered by large language models have been slowing moving to the pulpit. Tools like

One of my New Year’s resolutions was to read one of the “classics of fiction” each month this year. I’m happy to report that I’m on pace to succeed.

One of my New Year’s resolutions was to read one of the “classics of fiction” each month this year. I’m happy to report that I’m on pace to succeed.

As AI insinuates itself into our world and our lives with unprecedented speed, it’s important to ask: What sort of thing are we creating, and is this the best way to create it? What we are trying to create, for the first time in human history, is nothing less than a new entity that is a peer – and, some fear, a replacement – for our species. But that is still in the future. What we have today are computational systems that can do many things that were, until very recently, the sole prerogative of the human mind. As these systems acquire more agency and begin to play a much more active role in our lives, it will be critically important that there is mutual comprehension and trust between humans and AI. I have

As AI insinuates itself into our world and our lives with unprecedented speed, it’s important to ask: What sort of thing are we creating, and is this the best way to create it? What we are trying to create, for the first time in human history, is nothing less than a new entity that is a peer – and, some fear, a replacement – for our species. But that is still in the future. What we have today are computational systems that can do many things that were, until very recently, the sole prerogative of the human mind. As these systems acquire more agency and begin to play a much more active role in our lives, it will be critically important that there is mutual comprehension and trust between humans and AI. I have