by Chris Horner

A choice of ‘cultural things’ I enjoyed in 2022 and which you might like, too. Some were from well before this year, but discovered by me in ’22. Novel, non fiction, concert, recording, exhibition. Here we go:

- Novel: The Odd Women – George Gissing.

This is the kind of novel which when read makes you wonder why it isn’t better known and more widely celebrated. The late 19th century saw a wave of plays and novels dealing with ‘the New Woman’ – the educated, worryingly independent, vote-seeking, bicycling women of the late Victorian/Edwardian age. Examples include Victoria Cross’s Anna Lombard (1901), Ella Hepworth Dixon’s The Story of a Modern Woman (1894) Many of these were predictable rubbish: marriage or death solves everything. Exceptions among plays are Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler, Shaw’s Mrs Warren’s Profession, and among novels HG Wells’ Ann Veronica (1909), but it’s the Gissing that is really the winner among novels. Gissing avoids most of the cliches and stereotypes and produces a narrative that is genuinely absorbing and a set of themes and characters one remembers long after the book is put down. Gissing is an odd fish: he has real empathy for the plight of the poor and the rejected (both here and in The Nether World and his more famous New Grub Street), but has an ‘official’ conservative ideology which, when he lets it, blocks him from being able to imagine how the agency of working class or (as here) mainly lower middle class women might work for their liberation. In this he isn’t alone: many great novelists have said more through their literature than their ‘official’ beliefs ought to allow them to do (think of Dostoyevsky) In The Odd Women, he largely lets his imagination take him places his philosophy could never encompass. The book emerges as a fascinating account of the situation of the ‘superfluous’ women of the 1890s – and shows how they either succumbed to or overcame the world that seemed to have no place for them.

This is the kind of novel which when read makes you wonder why it isn’t better known and more widely celebrated. The late 19th century saw a wave of plays and novels dealing with ‘the New Woman’ – the educated, worryingly independent, vote-seeking, bicycling women of the late Victorian/Edwardian age. Examples include Victoria Cross’s Anna Lombard (1901), Ella Hepworth Dixon’s The Story of a Modern Woman (1894) Many of these were predictable rubbish: marriage or death solves everything. Exceptions among plays are Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler, Shaw’s Mrs Warren’s Profession, and among novels HG Wells’ Ann Veronica (1909), but it’s the Gissing that is really the winner among novels. Gissing avoids most of the cliches and stereotypes and produces a narrative that is genuinely absorbing and a set of themes and characters one remembers long after the book is put down. Gissing is an odd fish: he has real empathy for the plight of the poor and the rejected (both here and in The Nether World and his more famous New Grub Street), but has an ‘official’ conservative ideology which, when he lets it, blocks him from being able to imagine how the agency of working class or (as here) mainly lower middle class women might work for their liberation. In this he isn’t alone: many great novelists have said more through their literature than their ‘official’ beliefs ought to allow them to do (think of Dostoyevsky) In The Odd Women, he largely lets his imagination take him places his philosophy could never encompass. The book emerges as a fascinating account of the situation of the ‘superfluous’ women of the 1890s – and shows how they either succumbed to or overcame the world that seemed to have no place for them.

2. Television: Severance (Apple TV+)

This is the dystopian story of Mark, an employee of Lumon Industries who agrees to a “severance” program in which his non-work memories are separated from his work memories – and he is employed with a team of other office workers who have had the same operation. Wonderfully designed and written with great acting from the entire cast (you can get all the details at the click of a mouse, so I won’t list names here: a series like this is a group effort), the nature of labour time, the emptiness of of ‘free time’ and the question of how the human, the technological and the corporate relate in capitalism are all brilliantly conveyed. In many ways it reminded me of JG Ballard’s novels and short stories (his Super Cannes, especially).

This is the dystopian story of Mark, an employee of Lumon Industries who agrees to a “severance” program in which his non-work memories are separated from his work memories – and he is employed with a team of other office workers who have had the same operation. Wonderfully designed and written with great acting from the entire cast (you can get all the details at the click of a mouse, so I won’t list names here: a series like this is a group effort), the nature of labour time, the emptiness of of ‘free time’ and the question of how the human, the technological and the corporate relate in capitalism are all brilliantly conveyed. In many ways it reminded me of JG Ballard’s novels and short stories (his Super Cannes, especially).

3. Non fiction: This Life Martin Hagglund.

This book manages to make an engaging an original philosophical case for a kind of political existentialism in clear and accessible language. Hagglund discusses why our nature as mortal beings defines who and what we are – our finitude – and then goes on to outline what he regards as the political stance that one ought to take in the light of that – democratic socialism, understood here as the overcoming of capitalism. We need to free ourselves from the hours spent servicing an economic and political behemoth that wastes the planet and our brief lives.

This book manages to make an engaging an original philosophical case for a kind of political existentialism in clear and accessible language. Hagglund discusses why our nature as mortal beings defines who and what we are – our finitude – and then goes on to outline what he regards as the political stance that one ought to take in the light of that – democratic socialism, understood here as the overcoming of capitalism. We need to free ourselves from the hours spent servicing an economic and political behemoth that wastes the planet and our brief lives.

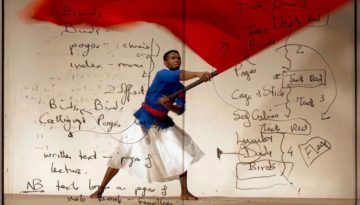

4. Exhibition: William Kentridge (Royal Academy, London)

I’ll keep this brief as the majority of readers won’t get to see this exhibition. None the less, it’s worth being alerted, since his work is shown globally, and you shouldn’t miss him if you get the chance. He is, I guess, South Africa’s most famous living artist. His work includes etching, drawing, collage, film and sculpture to tapestry, theatre, opera, dance and music. He developed his early work during the apartheid regime and his amazing large-scale productions and animations have since been widely shown: rooms of 4-metre wide tapestries, his signature charcoal trees and flowers, and the breath-taking three-screen film, Notes Towards a Model Opera. There is humour, politics, melancholy and sheer amazement for anyone who immerses themselves in a major show like this. Catch him if he appears anywhere near you.

I’ll keep this brief as the majority of readers won’t get to see this exhibition. None the less, it’s worth being alerted, since his work is shown globally, and you shouldn’t miss him if you get the chance. He is, I guess, South Africa’s most famous living artist. His work includes etching, drawing, collage, film and sculpture to tapestry, theatre, opera, dance and music. He developed his early work during the apartheid regime and his amazing large-scale productions and animations have since been widely shown: rooms of 4-metre wide tapestries, his signature charcoal trees and flowers, and the breath-taking three-screen film, Notes Towards a Model Opera. There is humour, politics, melancholy and sheer amazement for anyone who immerses themselves in a major show like this. Catch him if he appears anywhere near you.

5. Movie: Drive My Car Directed by Ryusuke Hamaguchi after a short story by Haruki Murakami.

This is the film of the year – something that brings together all the elements that make a great movie. It’s a long film (180 minutes) but it earns every second of its running time. The first hour of the film is in effect a prologue that one has to experience in order to understand the actions and feelings of the characters later on: perhaps surprisingly, this is very effective. The cinematography alone ought to make it an award winner, but the story – about love, grief and self acceptance – is so well conveyed as to be quite memorable. An actor/director mourning the sudden death of his wife and beginning to come to terms with her various betrayals, bonds with the young woman who is hired to drive him during a residency in Hiroshima, where he is involved in the production of Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya. An online like this cannot do it any justice: you have to see it

This is the film of the year – something that brings together all the elements that make a great movie. It’s a long film (180 minutes) but it earns every second of its running time. The first hour of the film is in effect a prologue that one has to experience in order to understand the actions and feelings of the characters later on: perhaps surprisingly, this is very effective. The cinematography alone ought to make it an award winner, but the story – about love, grief and self acceptance – is so well conveyed as to be quite memorable. An actor/director mourning the sudden death of his wife and beginning to come to terms with her various betrayals, bonds with the young woman who is hired to drive him during a residency in Hiroshima, where he is involved in the production of Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya. An online like this cannot do it any justice: you have to see it

6. Music: Mahler, Symphony No 7 – Berlin Philharmonic orchestra, conducted by Kirill Petrenko.

This was a concert in the Royal Albert Hall (part of the London Proms), in September. The same orchestra and conductor can be seen and heard in this piece on the orchestra’s streaming website and Petrenko conducts the it with a different orchestra (the Bayerische Staatsoper) on CD. All are worth your time as Petrenko has the ability to move the players to quite exceptional levels of brilliance. Symphony no 7 is supposed to be a problem work, with questions of the tone of the final movement in particular giving many performances a real problem – is it meant seriously or is it ironic? The symphony as a whole is imbued with the sense of dream and nightmare, apparitions, horrors and bliss. Impending fragmentation seems threaten it. Schoenberg loved it for that, I think, and it can be seen as marking the beginning of modernism in music.

This was a concert in the Royal Albert Hall (part of the London Proms), in September. The same orchestra and conductor can be seen and heard in this piece on the orchestra’s streaming website and Petrenko conducts the it with a different orchestra (the Bayerische Staatsoper) on CD. All are worth your time as Petrenko has the ability to move the players to quite exceptional levels of brilliance. Symphony no 7 is supposed to be a problem work, with questions of the tone of the final movement in particular giving many performances a real problem – is it meant seriously or is it ironic? The symphony as a whole is imbued with the sense of dream and nightmare, apparitions, horrors and bliss. Impending fragmentation seems threaten it. Schoenberg loved it for that, I think, and it can be seen as marking the beginning of modernism in music.