by Akim Reinhardt

Last week marked the 20th anniversary to the start of America’s recently concluded second Gulf War. It’s also been nearly 33 years since the much shorter first Gulf War, a.k.a. Desert Storm (1990–91). Unlike the “great” wars, these haven’t merited Roman numerals.

My own Roman numerals now begin with an L. I am oldish. One of the advantages is that I can conjure fairly clear, adult memories of things that happened quite a while ago. Not just the fragmented, highly impressionistic snapshots leftover from childhood, but recollections of complex interactions and evolving ideas. As a professional historian, I know that some healthy skepticism is called for; such memories are not always reliable and cry out for corroboration. However, as we look back on the Gulf Wars, I’m not interested in reciting history so much as thinking about what they have meant to me. Me: a lifelong American who has never been in the military, but has friends who served in both Gulf Wars, some of whom still struggle with it; me as someone who felt mildly conflicted about the first Gulf War and opposed it meekly, but who spoke out more stridently against the second one.

I was 22 years old when George Bush the elder cast his thousand points of light over Baghdad. I used that war as an excuse not to dodge the draft (there was none), but to dodge work. When the bombs began falling, I called the hospital where I clerked the midnight shift hanging x-rays on alternators, and told them I was taking a personal day, or rather a night, to stay home and watch the news; I had family in Israel, against whom Saddam Hussein was launching batteries of SCUD missiles. It was barely the truth. I do have some very distant family in Israel, but they migrated there from Poland a century ago, I’ve never communicated with any of them, and know nothing of them other than the surname they share with my mother’s family. I used them as an excuse to stay home and watch television, like most Americans. Read more »

My favorite bookstore closed this month. Well, my favorite bookstore in Zurich, where I live. Also it hasn’t actually closed, it’s only changing hands. But

My favorite bookstore closed this month. Well, my favorite bookstore in Zurich, where I live. Also it hasn’t actually closed, it’s only changing hands. But

The season finale of

The season finale of  Two weeks ago, outside a coffee shop near Los Angeles, I discovered a beautiful creature, a moth. It was lying still on the pavement and I was afraid someone might trample on it, so I gently picked it up and carried it to a clump of garden plants on the side. Before that I showed it to my 2-year-old daughter who let it walk slowly over her arm. The moth was brown and huge, almost about the size of my hand. It had the feathery antennae typical of a moth and two black eyes on the ends of its wings. It moved slowly and gradually disappeared into the protective shadow of the plants when I put it down.

Two weeks ago, outside a coffee shop near Los Angeles, I discovered a beautiful creature, a moth. It was lying still on the pavement and I was afraid someone might trample on it, so I gently picked it up and carried it to a clump of garden plants on the side. Before that I showed it to my 2-year-old daughter who let it walk slowly over her arm. The moth was brown and huge, almost about the size of my hand. It had the feathery antennae typical of a moth and two black eyes on the ends of its wings. It moved slowly and gradually disappeared into the protective shadow of the plants when I put it down. Philosopher Harry Frankfurt is best known for his article-turned-manuscript On Bullshit, in which he distinguishes between lying and bullshitting. Most of us are raised to condemn liars more than bullshit artists, but Frankfurt makes the claim that we’ve all got it backwards. His argument is philosophical, rather than scientific, which means observable evidence is hard to come by, but recent political events have filled the gap.

Philosopher Harry Frankfurt is best known for his article-turned-manuscript On Bullshit, in which he distinguishes between lying and bullshitting. Most of us are raised to condemn liars more than bullshit artists, but Frankfurt makes the claim that we’ve all got it backwards. His argument is philosophical, rather than scientific, which means observable evidence is hard to come by, but recent political events have filled the gap.

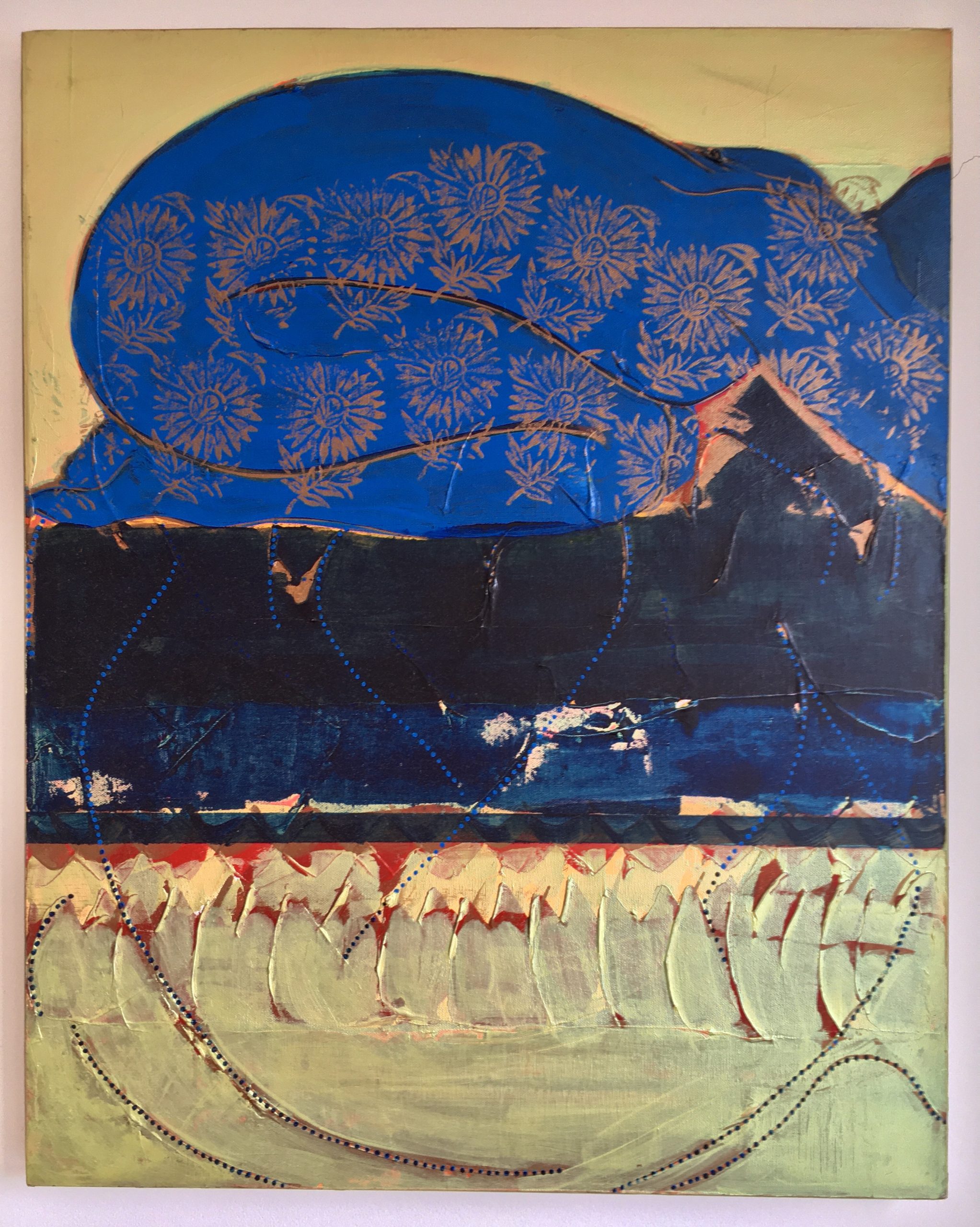

Sughra Raza. Untitled. Cambridge, 1999-2000.

Sughra Raza. Untitled. Cambridge, 1999-2000. Having

Having

On the night of July 13, 1977, the old god Zeus roused from his slumber with a scratchy throat. Reaching drowsily for the glass by his bedside, his arm knocked a handful of thunderbolts from the nightstand. Swift and white, they rattled across the floor to the mountain’s, his home’s, precipitous edge: off they rolled and dropped to plummet through the dark. That night, great projectiles of angular light splashed against and extinguished New York City’s billion fluorescent eyes.

On the night of July 13, 1977, the old god Zeus roused from his slumber with a scratchy throat. Reaching drowsily for the glass by his bedside, his arm knocked a handful of thunderbolts from the nightstand. Swift and white, they rattled across the floor to the mountain’s, his home’s, precipitous edge: off they rolled and dropped to plummet through the dark. That night, great projectiles of angular light splashed against and extinguished New York City’s billion fluorescent eyes.

When we speak about identity, we usually have in mind the various social categories we occupy—gender categories, nationality, or racial categories being the most prominent. But none of these general characteristics really define us as individuals. Each of us falls into various categories but so does everyone else. To say I’m a straight white male puts me in a bucket with millions of others. To add my nationality and profession only narrows it down a bit.

When we speak about identity, we usually have in mind the various social categories we occupy—gender categories, nationality, or racial categories being the most prominent. But none of these general characteristics really define us as individuals. Each of us falls into various categories but so does everyone else. To say I’m a straight white male puts me in a bucket with millions of others. To add my nationality and profession only narrows it down a bit.

There are two possible attitudes towards Scripture. One is to regard it as the direct and infallible word of God. This leads to certain problems. The other one, equally compatible with devotion, is to regard it as the recorded writings of men (it almost always is men), however inspired, writing at a specific time and place and constrained by the knowledge and concerns of that time. This invites deeper study of what was at stake for the writers, the unravelling of different narrative strands and voices, and discussion of whatever message the Scriptures may have for our own times. I expect that most readers here will adopt the second approach, while those who adopt the first are not to be dissuaded by mere rational argument, so why am I even discussing it?

There are two possible attitudes towards Scripture. One is to regard it as the direct and infallible word of God. This leads to certain problems. The other one, equally compatible with devotion, is to regard it as the recorded writings of men (it almost always is men), however inspired, writing at a specific time and place and constrained by the knowledge and concerns of that time. This invites deeper study of what was at stake for the writers, the unravelling of different narrative strands and voices, and discussion of whatever message the Scriptures may have for our own times. I expect that most readers here will adopt the second approach, while those who adopt the first are not to be dissuaded by mere rational argument, so why am I even discussing it?