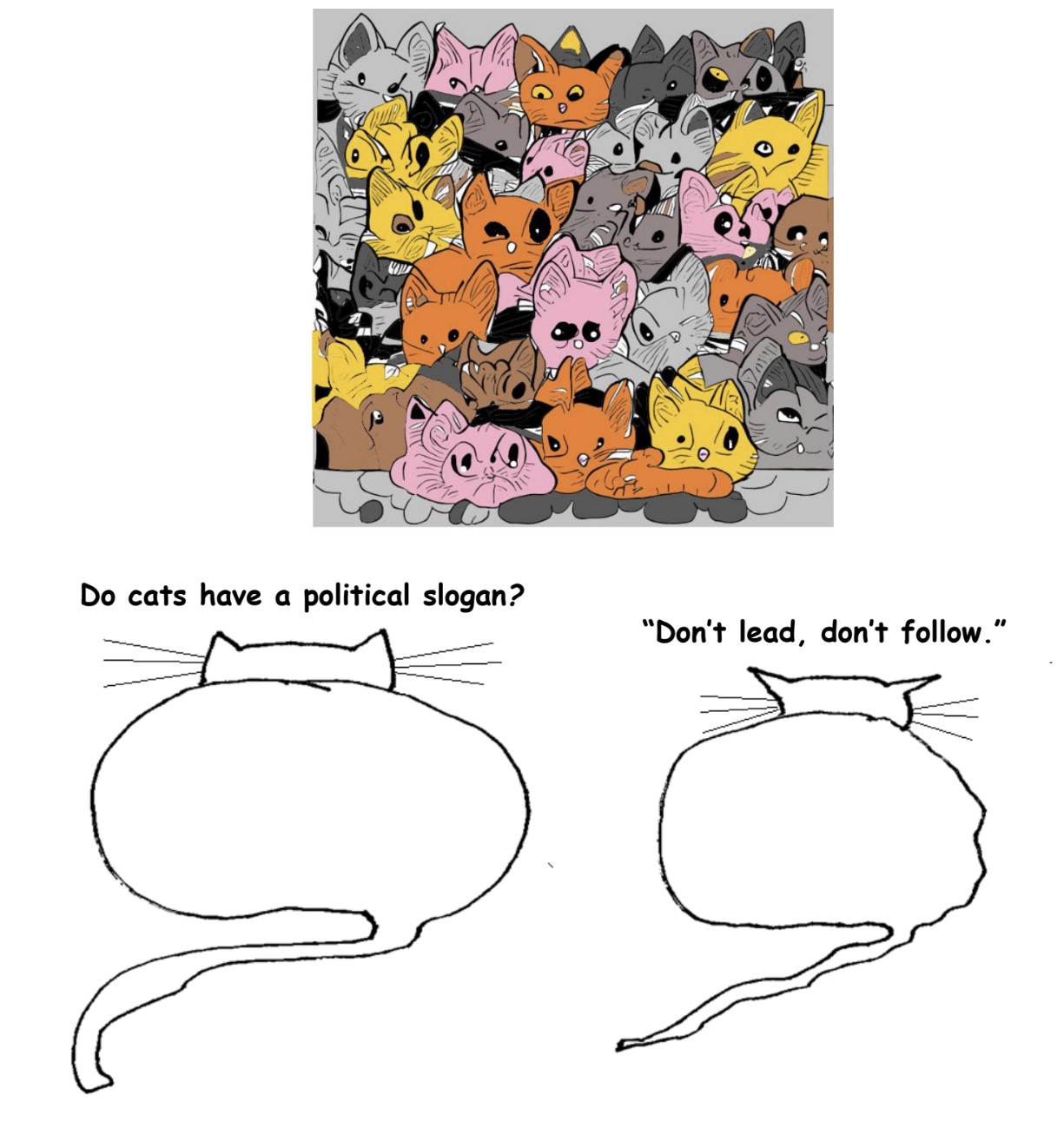

by Hirsch Perlman

Instagram: ecce_cattus

Sales: paxfeles.com

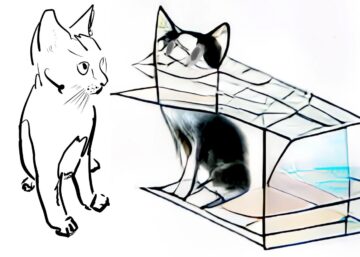

Ten months ago Artificial Intelligence helped lift me out of a stubborn pandemic depression. Specifically, an AI image generator’s results from the prompt Schrodinger’s Cat; the name of the physicist’s thought experiment in which, under quantum conditions, a cat in a box could theoretically be both dead and alive at the same time—that is until the box is opened and an observation is made.

Ten months ago Artificial Intelligence helped lift me out of a stubborn pandemic depression. Specifically, an AI image generator’s results from the prompt Schrodinger’s Cat; the name of the physicist’s thought experiment in which, under quantum conditions, a cat in a box could theoretically be both dead and alive at the same time—that is until the box is opened and an observation is made.

I wondered if and how AI would render a cat both dead and alive, or if it would just depict the box. And what other elements of the thought experiment it might create.

The results from the prompt were scribbles in need of completion, hallucinations of cats shimmering in and out of being. Tentative half formed felines hovering like sentence fragments lacking syntax and punctuation.

Sometimes it looked like the AI was capturing itself the nanosecond before I pressed the return key. It was as if I’d stumbled on AI picturing its own quantum state.

Starting with the AI scribbles, I redraw, combine, add to, and regurgitate never ending variations of cats in ambiguous spaces, ambiguous boxes. Boxes become cats or cats become boxes. What’s cat and what’s space is fluid, confused and melded- the cat deformed, carrying a bemused, malcontent, or often indifferent affect.

They’re allegorical mirrors: cat/cat and cat/box could be artwork/viewer, left brain/right brain, self/not-self, conscious/unconscious, tame/feral, or adaptive/maladaptive. Cats can mime any manner of relationship.

I’d found a deep digital rabbit hole. Read more »

I recently read the wonderfully ambiguous sentence, “The love of stone is often unrequited” in Jeffrey Jerome Cohen’s book Stone: An Ecology of the Inhuman. It inspired me to write love letters to stones.

I recently read the wonderfully ambiguous sentence, “The love of stone is often unrequited” in Jeffrey Jerome Cohen’s book Stone: An Ecology of the Inhuman. It inspired me to write love letters to stones. Nabil Anani. Life in The Village.

Nabil Anani. Life in The Village.

.

.

I simply can’t seem to stop writing the same essay over and over. This is, I admit, not a great opening to a new essay. If all I do is repeat myself, why bother reading something new from me? Fair enough. You’ve heard it all before. But allow me one objection, which is that many writers write the same novel repeatedly, many filmmakers create the same movie multiple times, and these are often the best novelists and filmmakers. Now, I don’t mean to put myself in this category, but I can take solace in the fact that the greats do the same thing I seem to be fated to do.

I simply can’t seem to stop writing the same essay over and over. This is, I admit, not a great opening to a new essay. If all I do is repeat myself, why bother reading something new from me? Fair enough. You’ve heard it all before. But allow me one objection, which is that many writers write the same novel repeatedly, many filmmakers create the same movie multiple times, and these are often the best novelists and filmmakers. Now, I don’t mean to put myself in this category, but I can take solace in the fact that the greats do the same thing I seem to be fated to do.