by Eric Bies

But—let’s be honest—to me he’s Dad.

But—let’s be honest—to me he’s Dad.

It’s just the sentence seems better how I have it up there in the title, more satisfying given its slight alliterative lilt, more interesting, rhythmically, to frustrate what otherwise would render as absolute sing-song.

My father is full of stories.

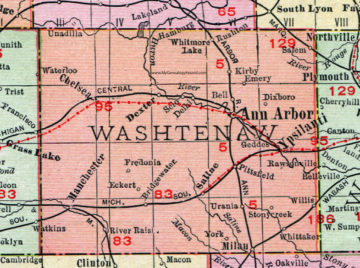

He grew up on a modest farm in a city—a town? a village?—what Wikipedia informs me is an unincorporated community, boasting “no legally defined boundaries or population statistics.”

In January of 2024, Dad’s dad will turn a hundred and three—if I were Julius Caesar I’d say CIII—a rather remarkable number and a very respectable age for a member of our species.

Dad’s dad doesn’t often figure in Dad’s stories. This is because Dad’s stories have everything to do with being five or six years old in the early sixties, running free on a modest farm in an unincorporated community whose citizenry we can’t call numberless but simply unnumbered.

Suffice to say where Dad grew up was and remains right on the perilous edge of what soft-palmed suburbanites like myself rarely shy from dubbing Nowhere.

It’s an exceedingly picturesque Nowhere—the kind of place people like me go to be turkeys, tracing the mazes and lanes of green corn to stand open-mouthed and drooping-combed beneath unassailable stretches of blue—and there’s nowhere I can picture Dad’s stories springing from but there.

When I was a boy Dad told me what it was like when he was a boy.

He talked and I gathered that danger was never far off—because, well, look: Dad had to grab the potatoes Grandpa (his) had forked up from the soil before the fork came menacingly down once more for more.

Dad fell from the treehouse and landed—wham!—flat on his back in a little red wagon.

Dad slipped from the seat of the tractor and would have gone under the tire, tall as a man, had his uncle not noticed he’d slipped.

Dad took aim with his air-powered pellet rifle, squeezed the trigger at a tree, and saw the pellet boomeranging back to land in the space between his eyes.

Dad was doused, working the fields, with DDT.

Which time he really almost did die.

But Dad’s stories have everything to do with making do.

And Dad’s stories have everything to do with the imagination.

After all, one was constantly being reminded of something.

There was God in the crosses on steeples, rock music fizzing and spilling from the radio, Gordie Howe on the cover of Sports Illustrated.

There was even the storied pelt of that land’s last wolf—a vast ratty ragged thing, hanging from a nail in the barn—shot down, I think, by Dad’s mom’s dad.

Dad, for his part, took shots at other critters.

The barn, for instance, was filled with bats. They roosted in the rafters. Sometimes they dropped down into the air and, in the dozens, perhaps the hundreds, cooked up a black cloud high above the bales of straw. One day Dad took aim with his air-powered pellet rifle, squeezed the trigger at the cloud, and—

But Dad never called it a cloud, did he? I’ve embroidered for effect. Disappear, therefore, cloud. Let it be (more so) as it was:

Bang!

The other bats bent their eights into figure nines. But one, just one, well, it froze. It hung there, painted into the fabric of the air for something smaller than a second, daintily did a little spin, and plummeted to earth.

I’m sure I haven’t heard him tell the story in twenty years. And I can’t say how many times I’ve heard it: maybe twice, maybe more. However many, when I did, I’m sure I asked to hear it again.

Years later I can hear him tell it the way he’d tell it. I can smell the manure. I think I can even see his feet leave the ground in a surge of some kind of triumph, crystalizing the incalculable, and I feel myself surging up toward the rafters with him.

Dad has other stories, a whole trove of them, though many, for me, have assumed the contour of a continuum.

Like how he hunted muskrats and sold their fur, tapped sap from maples to make syrup, pushed pucks around frozen ponds, and ruffled the nuns at school.

And though Mom, who grew up in a big city, likes to joke about how she tamed the country right out of him, he still lets fly the occasional impossible slang.

“Dad, what’s cattywampus mean?”

“Uneven,” he’d say. “Off; askew.”

And so I wonder now whether such exchanges weren’t the germ of my own inclination for stories, words. I did not grow up in a bookish household. Dad read the newspaper every morning from cover to cover, and Mom made a molehill out of the mountainous Sunday supplement, but books were few and far, and it’s something of a headscratcher how I ever entered into their textual pleasures. School, of course, was only an unclever impediment to happiness. By the time I entered ninth grade, having ceded every last bit of my attention to video games and cartoons, assigned readings had grown accustomed to remaining unread. (Even by the time I had turned things around, grades-wise, and was studying philosophy at UCLA, not to mention reading for pleasure, I continued to neglect homework, opting for the peculiar anonymity known only to those who have found themselves stalking the abandoned stacks of the Young Research Library at 9pm on a Sunday, where poems by Ezra Pound, essays by Guy Davenport, and novels by Thomas Bernhard beckoned.) When teaching irony to my students I myself stand as a handy example: Mr. Bies, who failed the first semester of freshman English, now teaches freshman English. In a way, perhaps because I’ve decided I must, I give thanks to the set of circumstances that enabled me to care so little for school when I was in it. There are no do-overs, and who wants one? Mom and Dad always said I could be anything I wanted to be, as long as it wasn’t illegal or immoral. College was an expectation but a vague one. I would go on to meet strange people who professed to having dreamt of attending this or that university since the age of six. I never took the SAT, am a slow learner, sometimes pretend to know more than I do. On the whiteboard hanging from a wall of the cubicle at the office where I worked out of school I wrote, one week in, ἄνδρα μοι ἔννεπε, μοῦσα, πολύτροπον, ὃς μάλα πολλά. To some nontrivial degree I am the stories my father fell to telling me. It’s time I started telling my own.