by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

From the very beginning of our marriage, my husband and I have spent an enormous amount of time side-by-side, silently looking at paintings. Mainly the Old Masters. We have many shared hobbies —and the older we get, the more these shared interests and passions tie us together. Even after ten years, I still love the way he appears in front of a masterpiece. He is totally awake. Sometimes we might talk a bit, hold hands, and exchange a smile, but mainly we stand there quietly soaking it all in.

That is perhaps why he immediately agreed to my plan to drive almost eight-hundred miles roundtrip in one day to see an ink painting from Japan.

“Well, I guess it isn’t that far to go….” He said, grabbing his phone to check the distance between our house in Pasadena and the museum in San Francisco, where the Asian Art Museum’s The Heart of Zen exhibition had opened to much fanfare.

“It’s a once in a lifetime chance,” I said.

“You always say that.” He looked amused and then asked, “How is it possible in twenty years in Japan you missed seeing this painting anyway?”

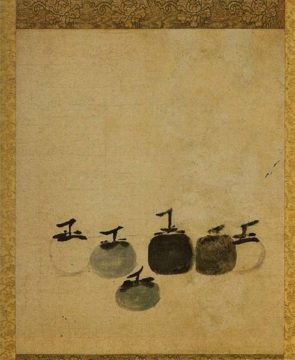

I had already told him countless times that in Japan, many masterpieces are kept away from public view, only trotted out once in a blue moon, when thousands of people line up to view it. And the 13th century painting Six Persimmons is not even kept in a museum. Painted with ink on paper by the Chinese Chan (Zen) monk Muqi, Persimmons is safeguarded in a Rinzai-sect Zen temple in Kyoto. Daitokuji temple only rarely displays the acclaimed picture—usually just once a year for a single day. And until 2019, it had never once been shown outside the temple even in Japan.

And so, I had missed it. Every single year.

But now—miraculously—it had crossed the ocean to be put on display for three weeks in San Francisco.

Six Persimmons is not only one of the most famous paintings in Japan, it is also a work venerated specifically in the tea ceremony. Over the years, I had seen reproductions of the picture in tea rooms more times than I cared to admit. Displayed always in autumn, the painting is usually said to represent a perfect expression of wabi-sabi. And of Zen Buddhism. Hence the title of the exhibition.

Occasioned by this special event, I decided to re-read Leonard Koren’s wonderful little book Wabi-Sabi: For Artists, Poets, and Philosophers. I must have it read four or five times. A delightful meditation on a key notion in both Zen and Japanese aesthetics, the book unpacks one of Japan’s “untranslatable” terms.

“The closest English word to wabi-sabi is probably rustic,” Koren explains. This is not a bad match, since rustic evokes the simplicity and unadorned quality of wabi-sabi. I’ve also heard wabi-sabi described in English as “an acceptance of beauty in something that is transient and imperfect.” And what, I ask you, is more humble and imperfect than those six persimmons?

After all, Muqi was not painting peonies. Or pine trees.

Persimmons lack all the cultural associations and symbolism of cherry blossoms or flying geese; things so celebrated in the arts of East Asia.

The humble and imperfect little persimmons capture something of the Zen imperative to slow down, quiet the mind, and allow the ordinary world to show up as it is.

A painting I had long hoped to see, it had alluded me for two decades. So, how wonderful it was to finally see it with my husband, just days before out ten-year wedding anniversary…!

2.

And so, we drove six hours one way by car to see it. I wish we could have stayed the night but it wasn’t possible, so we only had an hour in front of those six shining persimmons. Drifting in and out of focus, the two on the right and the two on the left floated side-by-side, pressed sweetly against each other, just like my husband and I were standing right there too, in front of them. Only the smallest persimmon was not perfectly lined up with the rest. Positioned in front, it is painted from a different perspective, from above. From that vantage point, we stood marveling at the curl of the leaves and the wonder of the stem.

Standing on the left and then on the right—and finally very close to the picture, you could see how each piece of fruit is a different size and a different shade—some more ripe than others. And all this is evoked in nothing but black sumi ink. The six persimmons seem to be hovering there in the bottom third of the painting—above which is nothing but empty space.

You might imagine them placed on a table, or perhaps lined up on a window ledge. Or maybe like I do, you picture them bobbing on the surface of water, like apples.

As Gary Snyder writes in his poem “Mu Chi’s Persimmons,” they are “the perfect statement of emptiness/ no other than form”

Dashed in fluid brushstrokes on highly absorbent paper, the persimmons appear like tiny rotating planets in the vast vacuum of empty space. In motion, floating, turning, levitating, and drifting. Lost in space?

It turns out that not much is known about the artist Muqi. But thanks to the fact that he signed some of his work “The monk from Shu [Sichuan], Fachang [his artist’s name], respectfully made this,” (蜀僧法常瑾制), we know he was born in Sichuan. Moving to the Southern Song Capital of Hangzhou, he began to study Zen Buddhism under a renown master.

He also presumably learned to paint.

Not particularly appreciated in the land of his birth, Muqi’s art would have been lost to history had not his posthumous career taken off in Japan.

It would be many years after the painter’s death when some of his ink paintings started arriving in Japan. This happened during the upheaval of the fall of the Southern Song and beginning of the Yuan dynasty, when religious exchanges between Zen temples in Japan and China began increasing. Many of Muqi’s works arrived carried in the bags of Chinese monks coming to Japan to teach. Or perhaps brought back from China in the trunks of Japanese monks. Persimmons arrived in the 15th or 16th century. From the hands of a monk into those of a great tea ceremony family in Osaka, the Chinese hand-scroll was then cut and then mounted as a hanging scroll for the tearoom. Adorned with precious brocade around the edges, it was then donated to Daitokuji temple, where it remains today.

It is interesting that a work so revered in Japan, received less praise in the land of its origin. But this re-valuing of simple and rustic items from abroad has happened several times in Japan. Six Persimmons is being referred in the US media as “Japan’s Mona Lisa”, but there is a similar story about another work of art, which is also often referred to as “Japan’s Mona Lisa.” This is a teabowl called the Kizaemon, which is a designated National Treasure.

In Japan, a National Treasure is a ranked cultural property, as determined by the Agency for Cultural Affairs (a special body of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology). The implication is that the nation’s government and people are putting resources behind the object’s protection, preservation, and study.

Of the eight teabowls registered as National Treasures in Japan, the Kizaemon is considered by tea practitioners to be the greatest work of all. A Japanese masterpiece.

And yet, like Muqi’s Persimmons, the Kizaemon was not made in Japan.

I will never forget the day I first saw a copy of the Kizaemon during my tea ceremony lessons. Focused on the intricate rules I had yet to master, I hadn’t looked at the bowl until the end of the practice, during the ritual appreciation of the tea utensils. At this stage my teacher would walk us through the points, or “places to appreciate” of each utensil.

I felt my head spinning. To call it a humble rice bowl would have been an understatement, for the teabowl was completely lopsided! Misshapen in the kiln, it stood up straight and steady enough, but the walls were warped. It had a lovely high foot, but numerous cracks and holes in the cheap glaze exposed the dark clay beneath. And to make matters worse, the bowl was ridged with ringed indentations from the potter’s wheel—there was nothing smooth or fine, no evidence of technical mastery.

I was trying so hard to delight in all things Japanese. But this ugly bowl?

The Kizaemon was first “discovered” by the Shogun’s army during an invasion of Korea, launched by the late 16th century shogun Hideyoshi Toyotomi. It was probably just an old rice bowl in a peasant’s house. But the shogun’s soldiers had been given strict instructions: bring home anything of beauty you find in your plundering. And this bowl fit the bill perfectly. It’s rustic simplicity and humble appearance embodied that supreme principle of Japanese tea ceremony aesthetics, that of wabi-sabi.

And so, this bowl made its way back to Japan – changing hands for greater and greater sums of money until it became priceless – a “treasure of the nation.”

Years later, I would finally get to see the real bowl, in a big exhibition of National Treasure ceramics held at the Tokyo National Museum. As I inched my way closer to it, the crowds became dense, and a great hush descended. Some people were crying. As it came into view, I felt its tremendous charisma. I was gobsmacked. And yes, I cried.

What a rags-to-riches story!

3.

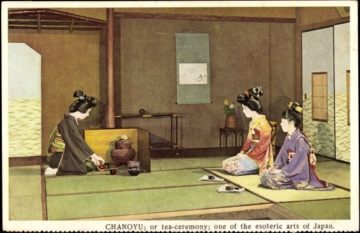

It is the tea ceremony that truly unites these two objects—ink painting and teabowl. Called chanoyu (or sado), tea ceremony has itself been informed by many different philosophies and traditions. But none more than Zen Buddhism.

Walking into a Japanese tearoom, the first thing one does after bowing and greeting the other participants is to go sit in front of the alcove. Called the tokonoma, the alcove is the place where art objects are displayed. Tea guests will go and sit at the alcove before taking their seat, often bowing first to the hanging scroll and then to the flower arrangement.

As Leonard Koren writes in his book Wabi-Sabi,

A perfunctory part of the tea ceremony as it exists today is paying formal attention to each object included in the ritual.

This is what is happening, when the ceremony begins and ends with the time set aside for formal attention paid –not just to the hanging scroll and the teabowl– but to the flowers and even to the charcoal used to heat the water. What was once a spontaneous occurrence, he explains, is now rigidly scripted. And yet by doing this, the hope is that students will be forced to slow down and pay attention –to be able to “see” those everyday occurrences like flowers or the smell of incense, and to bear witness to the everyday things in front of us (if only we slow down to notice them).

This is what the expression from Zen Buddhism ichi-go ichi-e (one time, one encounter) is trying to capture. Because every moment is a heightened moment. A perfect unfolding of “now:” And surely that is the miracle of the persimmons.

Humble, rustic, and a celebration of the blessings of the everyday, the timeless image reminded me of one of my favorite poems in the world—which is a great expression of the sabi in wabis-sabi:

Tao Yuanming’s poem, Plucking chrysanthemums by the eastern fence:

飲酒詩 陶淵明

結盧在人境 而無車馬喧

問君何能爾 心遠地自偏

採菊東籬下 悠然見南山

山氣日夕佳 飛鳥相與還

此還有真意 欲辨已忘言

Drinking Wine (#5)–Tao Yuanming

I’ve built my house where others dwell

And yet there is no clamor of carriages and horses

You ask me how this is possible– (And so I say):

When the heart is far, one is transported

I pluck chrysanthemums under the eastern fence

And serenely I gaze at the southern mountains

At dusk, the mountain air is good

Flocks of flying birds are returning home

In this, there is a great truth

But wanting to explain it, I forget the words

(my trans)

It is in nature where we can find truth. To be untrammeled and easily satisfied. Six persimmons: so unassuming and so charming. So simple and direct. And so perfect.

June 9, 2023, San Francisco — Dr. Jay Xu, the Barbara Bass Bakar Director and CEO, is delighted to welcome audiences to The Heart of Zen at the Asian Art Museum—Chong-Moon Lee Center for Asian Art & Culture, an exclusive showcase of two equally unmissable masterpieces: Persimmons (popularly known as Six Persimmons) and its companion Chestnuts. Cloistered in a Kyoto temple, Six Persimmons is a storied, centuries-old ink painting originating from China that was once considered the ultimate expression of Zen Buddhism. Designated as Important Cultural Properties in 1919, these exceptional artworks, rarely on public display, will be leaving Japan for the first — and perhaps only — time ever for this extraordinary special exhibition.

In tune with the seasonality of the late fall fruits they depict, and to safeguard these delicate works from light overexposure, first Six Persimmons and then Chestnuts will be presented individually, one at a time, for only three weeks each, Nov. 17–Dec. 10, and Dec. 8–31, respectively (there will be one weekend when both paintings are on display together, Friday, Dec. 8–Sunday, Dec. 10).

Notes:

The painting of Six Persimmons is designated one rank below that of National Treasure as Important Cultural Property. These treasured objects carry tremendous prestige, attracting large crowds to every viewing opportunity and subjects of countless books and documentaries. And they are not often permitted to leave Japan. But in this case, the Abbot of Daitokuji on a visit to San Francisco in 2017, when he gave a talk about the tea ceremony, offered to lend Persimmons, along with its lesser known paired painting, Chestnuts, to the city. The pictures will be on display in the museum for three weeks each –not at the same time, so looks like we will be heading back to San Francisco again this month—but hopefully not as a day trip!

- For more about second marriages and looking at paintings with my husband (but mostly about birds) please see my essay, in Aeon Magazine

- The great tea master Sen-no-Rikyu would write that “among the various properties and implements in the art of tea nothing is more important than a scroll [hanging in the tea room alcove usually with calligraphy by an awakened Buddhist.]” For more about the tea ceremony, see Dreaming in Japanese Wabi-Sabi.

- Leonard Koren’s jewel of a book, Wabi-Sabi: For Artists, Poets, and Philosophers

- Mu Chi’s Persimmons, by Gary Snyder (Poem in the New Yorker, 2008) video

There is no remedy for satisfying hunger other than a painted rice cake—Dogen 1242

- For more about the Kizaemon teabowl, please see my essay “Christopher Hitchens and the Korean Teabowl,” in Stanford archaeologist Patrick Hunt’s website Electrum Magazine: Why the Past Matters

- I cannot recommend this lecture about the exhibition enough (held at the Asia Art Museum in SF)

- And here is a lecture by the late great Berkeley professor James Cahill on Six Persimmons.