by Derek Neal

Alberto Moravia’s 1960 novel Boredom begins and ends with the narrator, Dino, describing his relationship to external reality. He does this, in the first instance, by describing a drinking glass, and in the second instance, by describing a tree. Here are Dino’s thoughts in the prologue:

“The feeling of boredom originates for me in a sense of the absurdity of a reality which is insufficient, or anyhow unable, to convince me of its own effective existence. For example, I may be looking with some degree of attentiveness at a tumbler. As long as I say to myself that this tumbler is a glass or metal vessel made for the purpose of putting liquid into it and carrying it to one’s lips without upsetting it—as long as I am able to represent the tumbler to myself in a convincing manner—so long shall I feel that I have some sort of a relationship with it, a relationship close enough to make me believe in its existence and also, on a subordinate level, in my own. But once the tumbler withers away and loses its vitality in the manner I have described, or, in other words, reveals itself to me as something foreign, something with which I have no relationship, once it appears to me as an absurd object—then from that very absurdity springs boredom, which when all is said and done is simply a kind of incommunicability and the incapacity to disengage oneself from it. But this boredom, in turn, would not cause me to suffer so much if I did not know that, although I myself have no relationship with the tumbler, such a relationship might perhaps be possible, that is, because the tumbler exists in some unknown paradise in which objects do not for one moment cease to be objects. For me, therefore, boredom, is not only the inability to escape from myself but is also the consciousness that theoretically I might be able to disengage myself from it, thanks to a miracle of some sort.” [emphasis mine]

And here is Dino in the epilogue:

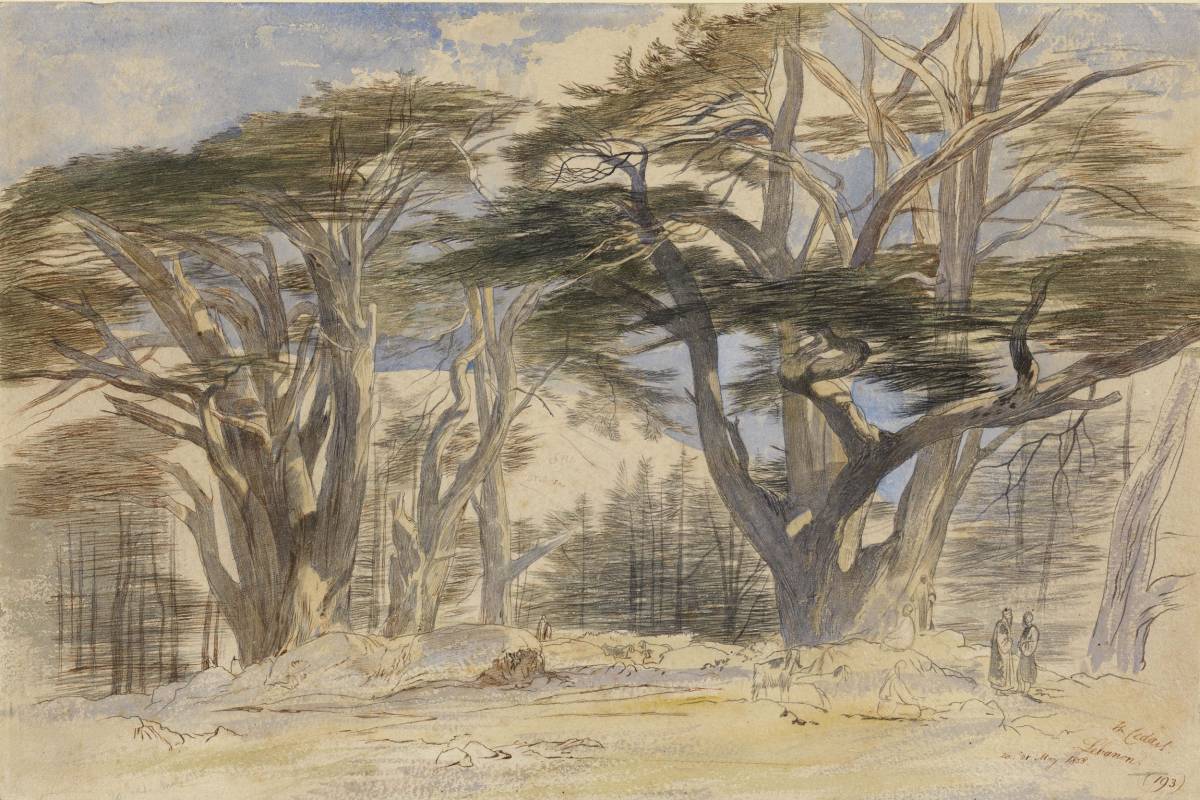

“As I have said, I spent hours gazing at the tree, to the great surprise of the nuns and the servants in the hospital, who said they had never seen a quieter patient than me. In reality I was not quiet, merely I was closely occupied with the only thing that truly interested me at that moment, the contemplation of the tree. I had no thoughts, I simply wondered when and how I had recognized the reality of the tree, had recognized, in other words, its existence as an object which was different from myself, had no relationship with me, and yet was there and could not be ignored. Evidently something had occurred just at the moment when I hurled myself off the road in my car; something which, to put it plainly, might be described as the collapse of an insupportable ambition. I now contemplated the tree with infinite complacency, as though to feel it different from myself and independent of me were the only thing that gave me pleasure…” [emphasis mine]

The change that occurs in the novel is one of consciousness.

In the beginning and throughout most of the story, Dino attempts to control and possess his external surroundings. He does this by “represent[ing] the tumbler to [him]self in a convincing manner,” meaning that he does not consider the real object but his mental representation of it. In doing this, he imagines the glass in terms of its role or function, which allows him to feel that he has a relationship or a connection to it, and thus that it is something he can understand and control. The glass is not grains of sand melted at a high temperature and cast in a rounded shape, closed at one end and open at the other; it is simply an object used for drinking. This attitude towards reality causes Dino to connect the existence of the “tumbler” with his own existence because Dino sees the glass as a means, not an end. If he cannot envision a purpose for the glass, it ceases to exist, which leads to him becoming trapped within himself; he cannot imagine a purpose for himself either but cannot escape his consciousness. In other words, he cannot believe in his own existence, yet he cannot deny its reality either. This culminates in the feeling of boredom for Dino, which is Moravia’s term for what has also been called the absurd, alienation, or meaninglessness.

This may seem like a lot of trouble to make over a glass, but Moravia simply uses the object of the glass to introduce his concept of boredom. He could have chosen anything, and indeed, once the narrative begins we find that Dino’s attitude towards the glass is also his attitude towards people; in particular, the character of Cecilia. Cecilia is Dino’s love interest, but she is wholly indifferent to him and in this way serves as a metaphor for reality. Dino’s attempts at controlling her—first through the physical act, then through money, and finally through marriage—reveal him to have a solipsistic worldview: Cecilia only exists in relation to him, not on her own. He tries to “represent” her just as he does with the glass; he gives her money so that he can cast her in the role of prostitute, then he proposes to her so that she can play his wife. He cannot imagine her outside of a role that society allows for her, so he never regards her as what she actually is: an autonomous human being.

In an essay on Boredom, Nicola Chiaromonte characterized Moravia’s novels in this way: “all Moravia’s work arises and is written as the result of the decision to accept the state of boredom as a fact; he stops at boredom and is incredulous of any further revelation. Therefore, he does nothing but reiterate that the daily world, the so-called natural and normal world which most people accept as the ultimate reality, is indeed the only reality, in that no other reality is given. Yet it is also a world of boredom, a dead world in the full sense of the word, a world that shuts us off from, rather than leads us into relation with, reality.”

This description may be true of the majority of Moravia’s work, but it seems as if Chiaromonte has skipped the epilogue of Boredom, which expresses a completely different sensibility. Indeed, in this section the world that Moravia describes is not dead but fully alive. Another world, another reality is possible: a spiritual one. This is not to say that the external world has changed, but that Dino’s consciousness is wholly different at the end of the novel than at the beginning.

In regarding the tree, he says that he “had recognized…its existence as an object which was different from myself, had no relationship with me, and yet was there and could not be ignored.” This is in contrast to the prologue, where he fixates on the idea that, even though he has no connection to the tumbler, “such a relationship might perhaps be possible, that is, because the tumbler exists in some unknown paradise in which objects do not for one moment cease to be objects.” In reading the epilogue, we might think that Dino has entered into the paradise that he’s been searching for, but this is not the case. He still has no relationship with the tree; however, instead of fighting against this by constructing a mental representation of an object to create a relationship (imagining the tumbler’s function as a container for drinks), he accepts the object as it is—in this case, the tree—which allows the tree to exist on its own terms. Dino gives up his “insupportable ambition,” which allows him to see the tree as an end, not a means. In this way, Dino can banish boredom and his overbearing self-consciousness.

This is true in regard to his relationship with Cecilia as well. Dino says that “as soon as I began to think about Cecilia again, I was aware of the same thing happening to me as when I gazed at the tree through the window.” He continues: “I was sure that Cecilia, in her own economical, inexpressive way, was happy, and I was astonished to find that I was pleased. Yes indeed, I was pleased that she should be happy, but above all I was pleased that she should exist, away there in the island of Ponza, in a manner which was her own and which was different from mine and in contrast with mine, with a man who was not myself, far away from me. I was here in the hospital I repeated to myself from time to time, and she was at Ponza with the actor, and we were two different people and she had nothing to do with me and I had nothing to do with her, and she was apart from me, and I was apart from her. And finally I no longer desired to possess her but to watch her live her life, just as she was, that is, to contemplate her in the same way that I contemplated the tree outside my window. This contemplation would never come to an end for the simple reason that I did no wish it to come to an end, that is, I did not wish the tree, or Cecilia, or any other object outside myself, to become boring to me and consequently to cease to exist. In reality, as I suddenly realized with a feeling almost of surprise, I had relinquished Cecilia once and for all; and, strange to relate, from the very moment of this relinquishment, Cecilia had begun to exist for me.”

At the end of the novel, Dino reaches a state of what Susan Sontag refers to, in an essay on Robert Bresson’s cinema, as “spiritual balance.” In describing Bresson’s “spiritual style,” Sontag writes that “the form of Bresson’s films is designed to discipline the emotions at the same time that it arouses them: to induce a certain tranquillity in the spectator, a state of spiritual balance that is itself the subject of the film.” I was astonished when I read these words. To think that a film or a work of art is not about what happens in the narrative or even how it happens, but how the way in which it happens creates an effect on the viewer/reader, is a fascinating notion. It is obvious in its simplicity—why else would someone engage with a work of art if it did not induce some effect upon them—but it is one that is rarely articulated, perhaps because it is difficult to express the effect a work of art has upon us without resorting to cliché or seeming overly subjective, thus invalidating one’s assessment.

I read Sontag’s essay after reading Paul Schrader’s essay on “transcendental style,” and I have begun to think about how the spiritual or transcendental style that they discuss in film could be applied to literature. Last month I wrote about Schrader’s conception of “boredom as an aesthetic tool” and proposed that the cultivation of boredom may be a necessary step on the path to transcendence. After reading Sontag’s essay, I am even more convinced of this. Sontag notes that “Reflective art is art which, in effect, imposes a certain discipline on the audience—postponing easy gratification. Even boredom can be a permissible means of such discipline.” In Boredom, we have an entire novel dedicated to this idea.

Dino is bored, immensely bored throughout the majority of the story, and as the novel is written in the first person, the reader begins to become bored as well. This is Moravia’s way of preparing us for the transcendence of the epilogue: for the reader to experience and understand the spiritual state that Dino enters at the end of the novel, we too must identify with his boredom. Only then can we leave the mental world that shuts us off from reality, as Chiaromonte says, and be lead into relation with reality.

In describing “transcendental style,” Schrader outlines a plot divided into three parts. The first part is boredom, which creates a “crack in reality.” The second part is a “decisive moment,” which assists the resolution of the story. The third part is transcendence, or Sontag’s “state of spiritual balance.” Schrader’s recent “man in a room” trilogy can easily be interpreted in this way; so too can Boredom.

The majority of the novel, as we’ve said, is devoted to the experience of boredom. This allows the reader to see a “crack in reality;” in this case, the superficiality of post-war Italian society, the emptiness of a life devoted to money; the hypocrisy of the aristocracy. The decisive moment is at the end of the narrative, when Dino veers off the road in an apparent attempt at suicide. Dino, instead of continuing to live in the false world, decides that death is preferable. His acceptance of death leads to a paradoxical result: he is finally able to live. This is, perhaps, the message of all great spiritual, philosophical, and religious traditions.

Moravia makes this interpretation of his work explicit in an interview from 1961 with French journalist Pierre Dumayet. Dumayet, referring to Moravia’s concept of boredom, asks, “isn’t there a solution to this apparently natural need to possess, according to you?”

Moravia responds: “Yes, there is a solution. It’s written in the conclusion. The solution, is the renunciation of the object and contemplation…You must give up on the object, so you begin to truly love it and then you contemplate it…Admitting the objective reality outside of ourselves, the person, the human person.”

Dino does this with Cecilia; he “relinquishes” Cecilia, and she begins to exist. He refuses to represent the tree, gives up his attempt at understanding it, and the tree begins to exist. He accepts death, and he begins to live.