by Daniel Gauss

When you walk through the gates to enter the B-52 Victory Museum in Hanoi, you immediately find the wreckage of what has been one of the most terrifying machines ever built: an American Boeing B-52 Stratofortress. Apparently, this wreckage largely came from Nixon and Kissinger’s “Christmas Bombings” of 1972.

When you walk through the gates to enter the B-52 Victory Museum in Hanoi, you immediately find the wreckage of what has been one of the most terrifying machines ever built: an American Boeing B-52 Stratofortress. Apparently, this wreckage largely came from Nixon and Kissinger’s “Christmas Bombings” of 1972.

The museum has the wreckage laid out to show the rough outline of a B-52, to give visitors some idea of how massive the plane was. It looks like a slain dragon lying there with gaping wounds. My friend Trang, a professor in Vietnam, marveled at the twisted gargantuan structure, wondering out loud what kind of country had the resources and will to make so many airplanes that were so large and destructive.

I witnessed visiting groups of Vietnamese who silently gathered around areas of the wreckage as there was an odd tranquility surrounding the dead beast. It had been dead for over 50 years and folks realized it would never rise again. Yet what lay mangled before us had once represented the apex of American power, when America unquestioningly thought it could win wars through sheer force and technological domination. This was the embodiment of what Theodore Roosevelt once called the “big stick” that we might sometimes use in our foreign policy.

The B-52 was never simply an airplane. It was a political instrument and a psychological weapon. Its very existence, capable of carrying nuclear weapons halfway across the world while being refueled in the air, gave the United States a terrifying aura during the Cold War.

Indeed, from 1961 to 1968, the U.S. Strategic Air Command (SAC) kept nuclear-armed B-52 bombers continuously airborne as part of Operation Chrome Dome. The B-52s flew routes over the Arctic, Atlantic and Mediterranean, staying within striking distance of Soviet targets. Crews flew 24-hour missions, with new crews taking over as others landed. Read more »

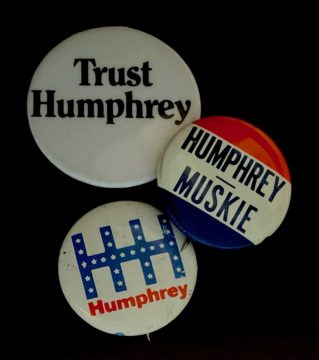

The broken-down jalopy that was Hubert Humphrey’s campaign wheezed its way out of Chicago and headed…anywhere but there. The Convention was an utter disaster. The only “bump” in the polls was a shove backwards, and Humphrey seemed to have nothing with which to shove back. He had no coherent message on the biggest issue of the day—Vietnam. He was working for an absolutely impossible boss, LBJ, who demanded complete loyalty and delighted in humiliating him. His campaign was broke…it literally didn’t have enough money to pay for orders of Humphrey buttons.

The broken-down jalopy that was Hubert Humphrey’s campaign wheezed its way out of Chicago and headed…anywhere but there. The Convention was an utter disaster. The only “bump” in the polls was a shove backwards, and Humphrey seemed to have nothing with which to shove back. He had no coherent message on the biggest issue of the day—Vietnam. He was working for an absolutely impossible boss, LBJ, who demanded complete loyalty and delighted in humiliating him. His campaign was broke…it literally didn’t have enough money to pay for orders of Humphrey buttons.