by Michael Liss

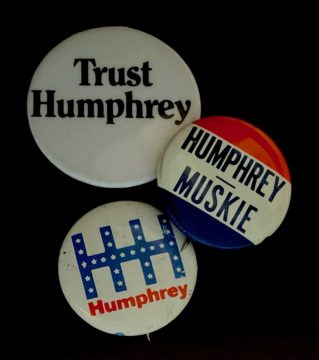

The broken-down jalopy that was Hubert Humphrey’s campaign wheezed its way out of Chicago and headed…anywhere but there. The Convention was an utter disaster. The only “bump” in the polls was a shove backwards, and Humphrey seemed to have nothing with which to shove back. He had no coherent message on the biggest issue of the day—Vietnam. He was working for an absolutely impossible boss, LBJ, who demanded complete loyalty and delighted in humiliating him. His campaign was broke…it literally didn’t have enough money to pay for orders of Humphrey buttons.

The broken-down jalopy that was Hubert Humphrey’s campaign wheezed its way out of Chicago and headed…anywhere but there. The Convention was an utter disaster. The only “bump” in the polls was a shove backwards, and Humphrey seemed to have nothing with which to shove back. He had no coherent message on the biggest issue of the day—Vietnam. He was working for an absolutely impossible boss, LBJ, who demanded complete loyalty and delighted in humiliating him. His campaign was broke…it literally didn’t have enough money to pay for orders of Humphrey buttons.

It didn’t end there. He was fighting the electoral realignment centrifuge that was ripping apart the New Deal Democratic coalition. The formerly Solid South was more than 20 years into its secession. The Party’s hold on the blue-collar family was being tested by the cultural appeal of George Wallace. Suburbanites were worried about the violence in big cities and wanted leadership to do something about it. In theory, they were moderates, supporters of the Civil Rights movement. In practice, many applied a NIMBY approach. The youth vote was inextricably connected to the anti-war vote; the war was inextricably connected to Johnson; and LBJ was inextricably connected to Humphrey.

All this the Humphrey team knew, with no clear path forward. Humphrey’s post-convention rallies were turning into disasters. He was booed and heckled, sometimes to the point of completely silencing him. His campaign understood that, to get his message out beyond the boos, they’d need to launch an advertising campaign, but they had no cash for it. The press soaked up and avidly reported every bit of negativity—including the uncomfortable truth that Humphrey didn’t even seem to know his own mind, so mealy mouthed he could be about anything controversial. About the only asset he had was the assistance of a real Kennedy man, Lawrence O’Brien. Few (if any) knew their stuff like O’Brien. He’d run JFK’s Senatorial campaigns in 1952 and ’58, had been White House Director of Legislative Affairs for both JFK and LBJ, and had served as Postmaster General until April of 1968, when he resigned to assist Bobby. Then, after RFK’s assassination, he moved over to help Humphrey. Later on, as DNC Chairman, he had the honor of having his office bugged by Richard Nixon’s plumbers.

Meanwhile, in the Park Avenue offices of the Nixon campaign, everything ran with the satisfying hum of a luxury sedan. Every detail was seen to. At the top was John Mitchell, Nixon’s law partner and future Attorney General. Money was gathered by Maurice Stans, and he produced it by the bushelful. Bob Haldeman was there, along with ad agency teams, image consultants, speech writers—and Roger Ailes. The candidate also had three Boeing 707s at his disposal. He named them for his daughters Tricia and Julie, and his son-in-law, David Eisenhower, grandson of the most popular man in America. David, who possessed the famous “Eisenhower Grin,” headed “Youth for Nixon” and apparently had a substantial number of avid followers in his own right.

The Nixon team built a meticulous campaign, each element carefully considered, each lesson learned from his 1960 loss to JFK applied. No Nixon promise to visit all 50 states, which had exhausted him with little electoral benefit. In 1968, he narrowed his attention to swing states he thought essential. He rested and kept up his tan with regular visits to Key Biscayne. His rallies and speeches were carefully stage-managed and rarely disrupted. Tickets to Nixon events involved screening—the advance team distributed more tickets than the number of actual seats, and security checked at the door. If you were a David Eisenhower type, you were in. A bit more hirsute and unkempt, or otherwise in a category of those who looked less likely to be a supporter, and you’d be told your ticket was counterfeit. A genuine Nixon strength—his grasp of policy—was parlayed into a series of soft-ball interviews with carefully chosen moderators and a pre-selected panel of “ordinary citizens.”

Several things stood out. Even though he was technically the challenger, this was not an insurgency. In certain ways, Nixon ran as if he were the incumbent. He refused to debate, not merely because of his memory of 1960’s disastrous “five-o’clock shadow” problem, but because he saw no reason to give the flailing Humphrey a stage on which he could look credible. On issues, he kept to platitudes, but in an interesting way. He identified a problem, blamed the current Administration for failing to deal with it, and said he would fix it, but not how. Just as he avoided debates, he also avoided any environment where he would be asked probing questions by people who understood policy and could do follow-ups. There was grumbling in the press about this, but Nixon’s machine was adroit at providing words devoid of substance.

Through August and almost all of September, Nixon’s variation on a “Front Porch” strategy worked as designed. A September 23rd poll by Harris had Nixon up by 8. One done for Gallup dated September 29 had him by 15. Kevin Phillips, one of his idea men (later the author of The Emerging Conservative Majority), thought he could win as many as 46 states. Nixon never was nearly that optimistic, but he was consolidating a coalition of traditional Republican voters, business, and those millions of “Forgotten Americans” who, by Nixon’s telling, worked hard, paid their taxes, and served their communities, their churches, and their country. Those folks, a Silent Majority, were rewarded by feckless (Democratic) politicians by being ignored, while danger awaited them both in Vietnam and at home. Nixon was there for them. He would bring Peace With Honor, and Law and Order, and a return to the happier days of the Eisenhower-Nixon Administration.

As things stood six weeks before Election Day, that looked very much like a winning hand. Still, Nixon was a worrier, and he could see things to worry about.

First, George Wallace was a wildcard. What had been initially thought of as another Dixiecrat campaign was turning out to be a lot more. His national poll numbers rose slowly but steadily to 21%. Obviously, he was strongest in the South, but his populist message had broader appeal than expected. Nixon’s team had to expect to lose some or all of the Southern states that Goldwater had taken in 1964: Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, and South Carolina. Would there be more leakage in the South, or would his alliance with Strom Thurmond help him through? What about Wallace’s impact in states he wouldn’t win, like the industrialized Midwest and North? How big was the outside-the-South Wallace vote, and from whom would it pull more? No one at the time could know for sure.

Second was structural to Nixon himself. He and his brain trust went for the higher-probability results—identify your voters, hold them, turn them out. See them, speak to them. Be aware that too much looking for new friends could alienate the ones you have (you can’t do outreach to Civil Rights activists and expect to keep Strom Thurmond in your corner). In times like 1968, where the country’s issues were great, don’t get experimental. The downside of this approach, what we would call a “base election,” was that it left little room for growth. This was exactly what happened: If you look at Nixon’s support on Election Day (43.42%) it was right where it was in poll after poll since August—never lower than an outlier Harris at 39%, never higher than a Gallup 45%. The Nixon people had constructed an ocean liner: stately, difficult to sink, but slow to maneuver.

The third was the dynamic between Humphrey and three Democrats—LBJ, Eugene McCarthy, and supporters of the late Robert F. Kennedy and the rest of the Kennedy network. It’s important to remember that Humphrey was the choice of the party bosses, and not the rank and file. There was residual affection for him because of his service to the party over the past two decades, but there wasn’t a happy groundswell for the Happy Warrior. By contrast, the McCarthy people and the Kennedy people had plenty of passion for their men. After they were mauled in Chicago, what passion they had for Humphrey was more of the negative type. He was, after all, Johnson’s humble servant, unwilling to cross his boss. That left him a relic, a creature of Party at a time when many of the most talented and energetic Democrats were followers of the two aspirational candidates, McCarthy and RFK. These people didn’t just fall into line—In fact, many of the most ardent boo-birds and hecklers Humphrey saw in September were angry McCarthy and Kennedy supporters.

Of course, there was a paradox here. The election wasn’t going to be Humphrey against McCarthy, or Humphrey against Kennedy. It was Humphrey against Nixon, and it was inarguable that Humphrey would deliver a lot more of their priorities. But this “lesser of two evils” rationale was something Democrats had never been good at. Labor Day passed, and there was no rapprochement and no real leadership towards a rapprochement. McCarthy had explicitly ruled out an endorsement as the Convention came to an end. At that point, he confounded everyone by essentially withdrawing from politics altogether—he went on a 10-day vacation to the South of France and then (and this is not a typo) reported in a literary style on the 1968 World Series for Life magazine. The phrase “Fall Classic” had a new twist.

Humphrey was in a box. For so long as he was bound and gagged by LBJ on the war he couldn’t reach out to the disgruntled wings of his party. Without them, he would be a certain loser, and certain losers take on an odor that discourages campaign contributions, so there would be no way to get his message out over the negative din. He had to do something big.

It’s not entirely clear that Johnson understood the more party-destroying aspects of his attitude toward Humphrey in early September, or, if he did, whether he cared. He was adamant “not to be the first President to lose a war” and prioritized it. It’s a paradox of American power that we can commit, without truly existential risk, enormous amounts of resources for extremely long periods of time. This sense of invulnerability convinces some political leaders to push their chips in, and keep them in. Then, they find themselves stuck in the mire, and so pass it on to the next guy to decide whether he wants to “take the loss.” Vietnam was Johnson’s Big Muddy. He held out for Peace With Honor to be obtained by exerting tremendous force. He insisted Humphrey back him. LBJ was a complex figure. He was getting advice from hawkish Generals who had an interest in continuing, but the mixing of his ego and his judgment blinded him to some things that would become obvious in the weeks to follow, at enormous cost.

Where did Nixon come into this? Vietnam and Law and Order were central to his planning. The two issues shared critical DNA—they were both emotionally charged and seemingly unsolvable before the Election. The patented Nixon style—point out the problem, blame others for it, claim he can fix it, but refuse to detail how he would do it—was perfect for an electorate wanting better. And Vietnam was perfect just the way it was—an untreated abscess splitting the Democratic Party in half.

A perfect Vietnam was Nixon’s real worry. It had to stay that way. No sudden breakthroughs in the Paris Peace Talks that promised a lessening of hostilities generally. And no letting Humphrey off the leash so he could join many of his fellow Democrats (and potentially swing voters) in calling for a halt to the bombing as an inducement for Hanoi to negotiate. Nixon, quietly, worked both sides of this in ways that did not reflect well on his character. He got closer to Johnson, sending Billy Graham to flatter him and even offer him a role on the world stage after his Presidency came to an end. And, using contacts that shouldn’t have been used, he kept a very close ear on what was going on in Paris, and in Saigon.

Up to late September, it was all working beautifully. Nixon was holding his base, and Humphrey wasn’t. The October 9th Gallup poll showed Nixon at 44%, Humphrey at 29%, and Wallace at 20%. Remember that polls are put in the field first before all the data is analyzed and then released, so these numbers were backwards looking by about 10 days, and thus showed voter preferences for the week ending September 28/29. Three key metrics: Nixon was losing just 4% of Republican voters to Humphrey and 8% to Wallace. Humphrey was losing 17% of Democrats to Nixon, and 20% to Wallace. Wallace led Nixon narrowly among Independents.

Yet things were about to change, in ways that Nixon feared. The first was that Humphrey, in his angst-ridden way, had reached the limit of his tolerance for heckling, engaging in self-correction, and perhaps even feeling a touch of Johnson-induced self-loathing. After a particularly gruesome day getting yelled at in Seattle, he decided he was finally going to challenge his President. He flew to Salt Lake City to meet with his staff and teed up the key question—if not now, when?

The team worked through the night. The back and forth, the self-editing, the double and triple checking, including with both George Ball (former Ambassador to the United Nations) and Averell Harriman (Johnson’s in-Paris primary negotiator) are worth several chapters of a book on their own, but the public didn’t see that part. Nor did it hear about Humphrey’s last-minute call to Johnson about the substance of Humphrey’s planned speech, and LBJ’s lack of enthusiasm. Nor about Nixon’s call to LBJ about 45 minutes before the speech was to air, asking whether LBJ was changing policy. Johnson wasn’t, and for good measure was angry enough to offer Nixon a line of counterattack.

What the public did see was a speech on September 30th in Salt Lake City where Humphrey told the nation that he would start substantive peace negotiations by unilaterally halting the bombing. He reserved the right to resume the bombing if the North Vietnamese failed to act in good faith at the negotiating table and on the ground. The speech was paid for by his campaign, having broken into every piggybank it had. The final draft had a run time of a bit more than 26 minutes. That left just enough time to include a fundraising pitch at the end, almost as an afterthought.

The Salt Lake City speech (you can find the text plus the markups and early drafts at the Minnesota Historical Society’s website) is not in the pantheon of great American speeches, but it was clear enough and effective. Humphrey was finally “his own man.” The public responded almost immediately—small dollar donations flowed in and, by October 10th, the campaign had banked a million dollars—not Nixon money, for sure, but significant for that time. Humphrey also made new friends (or reunited with old ones). He got endorsements from some anti-war figures, and less arms-length treatment from some Democratic electeds. The press pooh-poohed it, but couldn’t ignore that he’d set a new tone. Perhaps most importantly for Humphrey’s morale, his reception at rallies and with younger voters got a lot friendlier. The day after Salt Lake City, he traveled to the University of Tennessee and drew a cheerful, encouraging crowd. It was the first of many. The anti-war movement may not have had its champion, but at least it had a candidate.

Nixon was not happy. Besides putting a little wind in Humphrey’s sails, Humphrey’s new approach gave Nixon something he didn’t want—a clear difference on Vietnam, on which the voters could decide. This was not as bad as actual progress in the talks, but it placed additional pressure on him (which he resisted) to be more explicit on how he would end the war. Judging by his later conduct while in office, it is not clear that was his intention.

There was more to dampen Nixon’s mood. He and the race were about to get a second, completely unexpected and unplanned-for jolt—Vice Presidential problems. Humphrey’s choice, Ed Muskie of Maine, turned out to be a very good one. Muskie was calm, well-spoken, distinguished, and balanced. Muskie was an asset. Nixon’s man, Spiro Agnew, was less controlled, with less depth, and more likely to say something inappropriate. Still, it is not clear that this moved the needle much. But George Wallace’s pick was a lulu. On October 3rd, just five weeks before Election Day, Wallace held a press conference in Pittsburgh to introduce his Veep choice, retired Air Force General Curtis LeMay.

There are all kinds of explanations as to why Wallace did this. Part of this might have come from his reticence in running with anyone. He only selected a running mate because the majority of states required one to be on the ballot. An early choice, Kentucky’s Happy Chandler, who, as a former Governor and Senator might have added a bit of gravitas, was mysteriously vetoed by….someone who thought Chandler was insufficiently committed to segregation (he had also been Baseball Commissioner when Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier).

Chandler out, “Bombs Away LeMay” in. His first question from the press, “What would be your policy in the employment of nuclear weapons?” launched him into Dr. Strangelove territory. LeMay really liked nukes. Wallace himself tried to rescue him, but the General would not be rescued, and, in less than 10 minutes, any slim chance that the Wallace campaign might have had to attract rational people diminished substantially.

Wallace’s problem was a problem for both the main candidates, but it might have been a greater one for the Nixon campaign, particularly in the industrialized North and Midwest. That’s because a traditionally potent arm of the Democratic Party, the unions, had swung into action on Humphrey’s behalf with their membership. Meetings, pamphlets, even one-on-ones brought a message home that, whatever Wallace’s “cultural” pull, the fact was that Alabama ranked at or near the bottom on bread-and-butter metrics and issues that were important to working families. With Nixon still preaching traditional Republican economic orthodoxy, a significant number of union Democrats began to “return home.”

By Mid-October, three things were clearly happening: First, the Democratic Party machinery, even in its ragged state, was still able to raise money and get things done. Second, Humphrey, given a clean Vietnam issue to work with, and a friendlier environment generally, improved as a candidate. Third, Wallace’s support was gradually slipping away, and Nixon, while still leading, wasn’t getting new traction. The original Nixon “base” strategy was holding, but with the same structural defect in that it wasn’t set up to attract new voters. Accordingly, he stayed in the low 40s, and, with Humphrey gaining, the gap narrowed.

As prospects improved, so more Democrats, including prominent ones, joined the team. One big fish held out, Eugene McCarthy. He found reasons to say no, resisting his colleagues in the Senate and even his friends. Finally, someone with real leverage stepped in: A. Phillip Randolph, founder, in 1925, of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and a central player in the Civil Rights movement, took out a full page ad in The New York Times with the headline “An Appeal from Black Americans.” The ad was a letter from 31 people including Aretha Franklin, Jackie Robinson, Kenneth B. Clarke, and Dr. Martin Luther King Sr. It pulled no punches, asking Gene McCarthy whether he believed that Richard Nixon, who allied himself with Strom Thurmond, would resist the Wallace Movement. “You must know, as we do, that the election of Richard Nixon or George Wallace will produce a new era of social neglect at best, and repression at worse.” Four days later, just one week before Election Day, McCarthy relented and, in his strained, off-putting way, endorsed.

Time was running out for everyone, but the drama only intensified. A new factor, a possible gamechanger: the legitimate possibility of a breakthrough in Paris. The gist was that LBJ was getting a lot of signals—from the Russians, who were acting as intermediaries, from his own representatives, and from U.S. Intelligence—that the North Vietnamese were willing to accept the South Vietnamese at the peace talks, cease attacking them, and accept a demilitarized zone in return for cessation of the bombings. Johnson just needed to go first, to make it appear to the world that his actions induced their concessions, but they would follow right after to ratify a deal.

Johnson was briefing the three candidates, but with circumspection. By this time, he had come to realize that Nixon was no ally, especially after Nixon friend Senator Everett Dirksen called Johnson to say that Nixon was upset after hearing about possible diplomatic movement to help Humphrey get elected. On October 25th, Nixon told reporters about his suspicions, of course in the classic Nixonian “some people are saying…but I don’t believe…” way.

Johnson now had two enemies, the North Vietnamese and Nixon. He ordered intensified surveillance, while conducting diplomacy for the highest of stakes. On October 28th, Johnson decided to sign onto the plan. On October 29th, the Russians reaffirmed their willingness to participate. After midnight on October 30th, Johnson met with General Abrams, who flew in from Vietnam just for the face-to-face. Abrams advised him to proceed with the bombing halt. Johnson got word through French diplomats that South Vietnamese President Thieu would get a negotiating team to Paris in two days. The wheels were moving, and Johnson was to deliver a national address on October 31st announcing that there would be a cessation of the bombing on the following morning, November 1st. Talks were scheduled to commence November 6th, one day after the Election.

Shortly thereafter, LBJ received two calls, one informing him that a wired-in Democratic foreign policy expert had received word that John Mitchell was trying to stop the peace talks; the second, from Secretary of State Dean Rusk, that President Thieu suddenly needed more time to send a negotiating team to Paris.

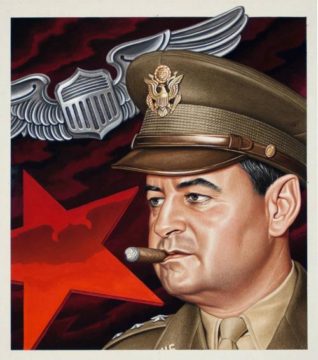

It’s likely that a fly in the Oval Office might have heard some of the juiciest, ripest, most pungent language ever. Johnson ordered more surveillance, and the results were deeply troubling. Bugs placed by U.S. intelligence indicated that Anna Chennault, born in Beijing, widow of the World War II hero General Claire Chennault of the famous Flying Tigers and a player in Republican politics (and fundraiser for Nixon), was acting as an intermediary between the Nixon Campaign, John Mitchell, South Vietnamese Ambassador Diem, and, through Diem, President Thieu.

Johnson went back to Dirksen, trying to send a message to Nixon to back off. He then called all three candidates to let them know he was speaking that evening to announce a permanent bombing halt and the immediate commencement of all-party talks in Paris. In some respects, it was already too late. It became clear that, after having indicated that they would, the South Vietnamese leadership had no intention of meaningfully participating. Johnson threatened to go without them, but they had already calculated the odds. They weren’t going to play because they had been told that they’d get a far better deal with Nixon as President. Johnson had a direct call with Nixon, but Nixon denied all. At this point, Nixon had played his hand perfectly, if dishonestly, and was not going to back off. Both men knew it. Three days before the election, there was Anna Chennault again, telling the South Vietnamese Ambassador to “Hold on. We are gonna win.”

It was clear to Johnson and his closest advisors what was going on. What they didn’t have was ironclad proof, and that set up the most profound of dilemmas. The allegation was radioactive. Every day, Americans were dying in Vietnam, over one thousand in both the months of September and October. Do you tell the voters or not?

This is the most curious part of the story. While a great many people, in the press, in the campaigns, in Washington, seemed to know part or most of what had gone on, few were willing to talk about it. For some, there was the tiniest smidgen of a doubt and the chance that they were putting too much weight on something that might only be inference. Others, particularly in the media, thought the decision to disclose, especially this close to the election, had to be made by the politicians.

So they all held back, if for different reasons. Johnson huddled with his advisors. National Security Advisor Walt Rostow was incensed and wanted the story out, but LBJ, Secretary of State Rusk, and Secretary of Defense Clark Clifford deemed it too corrosive to expose to the voting public, and too dangerous to American intelligence assets to have the extent of the surveillance disclosed. Johnson wouldn’t say anything. He passed the decision to Hubert Humphrey, who wouldn’t either.

Years later, in 2017, a key smoking gun was found in Bob Haldeman’s handwritten notes. Nixon to Haldeman: “Keep Anna Chennault working on SVN” and, speaking of the proposed talks, “Any other way to monkey-wrench it.”

The story didn’t break, and the election would be decided on other factors. It was going to be very close—the Humphrey team, seeing his momentum, just wanted one more day. They didn’t have it, and Nixon won by a slim but clear margin. Looking at the tallies, Nixon’s final popular vote edge was less than one percent, with Wallace settling at 13.52%. Nixon’s Electoral College margin was more convincing (301-191) but difficult to contextualize because of Wallace’s being on the ballot. One painful irony for Humphrey—no Mayor Daley came to the rescue. Nixon won Illinois and its 26 Electoral Votes.

In his Nixon, The Triumph of a Politician, 1962-72, Steven Ambrose—writing in 1989, before the disclosure of the Haldeman notes—rejects the idea that Nixon was directly involved in ruining Johnson’s Paris initiative. He does note something: Both men hosted election-eve nationwide telethons, Humphrey with Muskie; Nixon, without Agnew, but with the popular sports legend Bud Wilkinson. Roger Ailes produced Nixon’s. There came a moment when Nixon decided to take the opportunity to launch un-rebuttable comments about Johnson and the peace talks, calling them a political ruse that put American boys’ lives at risk. He punctuated it with the claim that he had heard a “very disturbing report” that, in just two days, “the North Vietnamese are moving thousands of tons of supplies down the Ho Chi Min Trail and American bombers are unable to stop them.” Ambrose’s comment: “He had heard no such report. He simply made that up.”

When talking about 1968, it seems somehow appropriate to give Ambrose the last word.

This is the fourth and final entry in the “1968” series. It has been a tremendous pleasure to write about, and even more to receive so many personal recollections in response.

Here are the links to the first three:

Part I, Darkness At The End Of The Tunnel

Part II: 1968 The Center Vaporizes

There are a lot of excellent books out there that cover 1968 far better than I have. A few, in no particular order, include: The Contest: The 1968 Election and the War for America’s Soul, by Michael Schumacher; Playing With Fire: The 1968 Election and the Transformation of American Politics, by Lawrence O’Donnell; for his extraordinarily acute eye, Garry Wills’ Nixon Agonistes: The Crisis of the Self-Made Man; and, for the authors’ dispassionate approach and different perspective, An American Melodrama: The Presidential Campaign of 1968, by three British journalists, Lewis Chester, Godfrey Hodgson, and Bruce Page.