by Brooks Riley

Though we are an aggregator blog (providing links to content elsewhere) on all other days, on Mondays we have only original writing by our editors and guest columnists. Each of us writes on any subject we wish, and the length of articles generally varies between 1000 and 2500 words. Our writers are free to express their own opinions and we do not censor them in any way. Sometimes we agree with them and sometimes we don’t.Below you will find links to all our past Monday columns, in alphabetical order by last name of the author. Within each columnist’s listing, the entries are mostly in reverse-chronological order (most recent first).

by Brooks Riley

by Carol A Westbrook

“Take two aspirin and call me in the morning” has been replaced by “Here’s a bottle of oxycodone. Don’t call me for a month.”

Two million Americans are addicted or dependent on opioid drugs. Last year, 72,000 of them died of overdoses, usually by accidentally taking too high a dose of an illicit drug. What has caught our attention is that these deaths are not the down-and-out, indigent drug addicts sprawled in dirty crack houses that are pictured on TV crime shows. They are our friends and family, teenagers and adults who unwittingly became addicted to medication that was legitimately prescribed to them by doctors.

Drug overdose deaths are rapidly increasing, as is apparent from the chart below, and are now the leading cause of deaths in adults under age 50. The cause of this epidemic is not drug pushers, or dirty needles, but the health care industry itself. It is the result of a series of well-meaning but misguided policy changes that appeared over the last twenty years that physicians such as myself were asked to implement in caring for patients with pain. Let me explain. Read more »

by Max Sirak

One of the things I love about sports is they’re a low-stakes environment in which to practice high-stakes skills. For most people, most of the time, the results of a sporting match don’t affect the long-term quality of their lives. This is what I mean by “low-stakes.” In the grand scheme and scope of our lives, the outcomes of games rarely matter. Which is what makes sports such a great place to practice skills that really can and do impact our lives for the better. This is what I mean by “high-stakes.”

One of the things I love about sports is they’re a low-stakes environment in which to practice high-stakes skills. For most people, most of the time, the results of a sporting match don’t affect the long-term quality of their lives. This is what I mean by “low-stakes.” In the grand scheme and scope of our lives, the outcomes of games rarely matter. Which is what makes sports such a great place to practice skills that really can and do impact our lives for the better. This is what I mean by “high-stakes.”

There are things we can all learn and hone in and through the context of playing or watching sports to help us build happier and healthier lives. Teamwork is one of them. Learning what it means to be part of a team, play well with others, and sacrifice individual accolades for the greater good are all lessons which can be gained and groomed via sports but apply to the larger fields of life.

The graceful handling of victory and defeat is another. Play or watch sports long enough, and you’ll eventually be given opportunities to encounter both ends of this spectrum. You’ll feel what it’s like to win and what sort of behaviors that warm feeling motivates. Likewise, you’ll also brush up against limitations and defeat and be given a chance to explore these colder consolations and the behaviors they motivate.

Working together, getting your way, or not are pretty obvious places where sports mirror life. No revelations here. Which is why I’d like to step away from the surface (whether hardwood, grass, water, ice, or clay…) and take some time to explore a more subtle realm, that of thought. Specifically, how the thoughts you think make you feel. Read more »

by Christopher Bacas

In the fall of 1970, I brought a Bundy tenor saxophone home from school. I was nine and in Mrs Farrar’s 5th grade class. To celebrate, my father slid an LP called “Soultrane”out of a blue and white cardboard jacket. The first sounds from the record player’s single speaker: a muscular folk song with rippling connective tissue that quickly spun free into endless cascades. Dad explained that it was my new horn, in the hands of John Coltrane. I didn’t know his name and nothing that day seemed possible, anyway.

In the fall of 1970, I brought a Bundy tenor saxophone home from school. I was nine and in Mrs Farrar’s 5th grade class. To celebrate, my father slid an LP called “Soultrane”out of a blue and white cardboard jacket. The first sounds from the record player’s single speaker: a muscular folk song with rippling connective tissue that quickly spun free into endless cascades. Dad explained that it was my new horn, in the hands of John Coltrane. I didn’t know his name and nothing that day seemed possible, anyway.

In the weeks before lessons began, I played. The mouthpiece looked better with the reed on top, tickling my upper lip, so it stayed that way. With the “Breeze Easy Method” book, I figured out the names and fingerings of most notes. I sounded out some songs. Certain combinations sounded good-a,c,d,e,g, adding d# and g# for seasoning. That became “my scale”.

In the first lesson, Holmes Royer, a man as elegant as his name, saw my set up and heard the squawks, he reached over and rotated my mouthpiece.

“Try this” he said, chuckling.

My pattern was set for life. I’d teach myself in marathon sessions and show up over-prepared but lacking some key skill; intonation, correct rhythms, steady tempo. My teachers must have chuckled often. Or cringed. Read more »

by Mary Kenagy Mitchell

Like Uncle Albert in Mary Poppins, I love to laugh. Luckily, I have some funny friends. The work of many talented professional comedians is as close as my phone. I go back to Arrested Development and The Office. And certain novels. I even find myself funny.

What I usually mean by laugh is that I smile enough to crease my cheeks and exhale quickly through my nose three or four times in a row. If something is really funny, I might make a sound in the back of my throat like a dog trying to bark with a muzzle on. This is not a courtesy laugh. I am genuinely entertained. I just don’t show it much.

Or sometimes nothing is exactly funny at all: I just mean I suddenly have perspective on myself. I laugh at myself because it took me so long to figure out that I turned out the way I did because I am a lazy person who was raised by compulsive workers. This laugh does not have a physical manifestation. It is only an idea of laughter.

At the other end of the spectrum, I occasionally I find myself laughing involuntarily, loudly, spasmodically, hard enough to bring tears, so hard that I couldn’t stop if I wanted to. Then, the smallest variation on the original joke starts the whole cycle again and I’m helpless. My eyes become damp. This laughter is a form of exercise. Read more »

by Joan Harvey

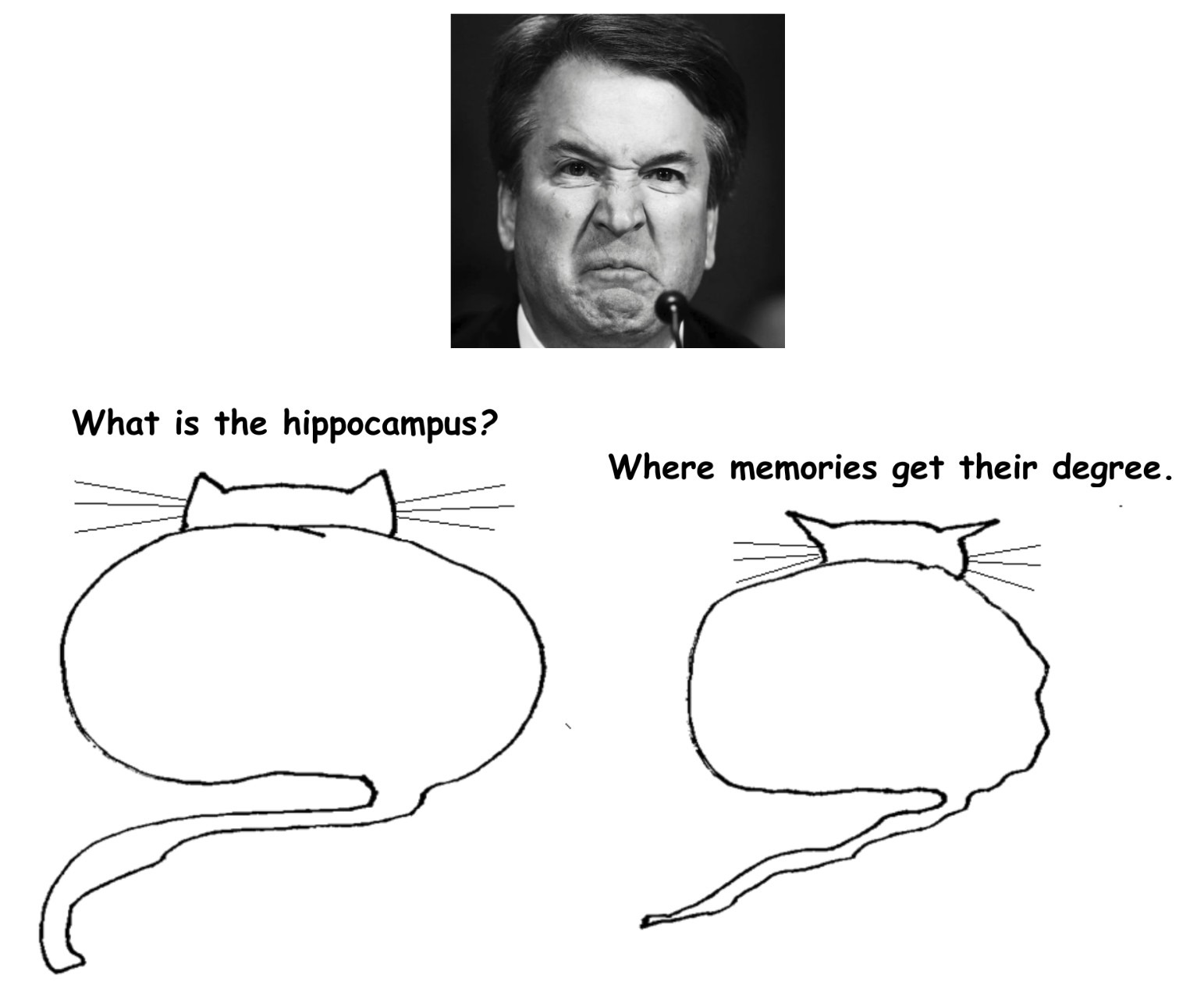

Somewhere on an island with sun and shade, in the midst of peace, security and happiness, I would in the end be indifferent to whether I was or was not Jewish. But here and now I cannot be anything else. Nor do I want to be. —Mihail Sebastian

Fascism is what happens when people try to ignore the complications. —Yuval Harari

These days, even in the somewhat remote hills where I dwell, near a very liberal, and mostly white town, one thinks often about the possibility of living soon in an authoritarian state. And this possibility becomes impossible to separate from the idea of identity—who is most at risk? Probably not me. But certainly many immigrants are already or could be in danger, whether Mexican or Muslim. Identity, as in the quote from Mihail Sebastian above, becomes an issue when it is forced on one. And, tangled up with identity is the difficult issue of identity politics, which is driving the right in a negative way, and splitting the left.

In his book The People vs Democracy, Yascha Mounk quotes sociologist Adia Harvey Wingfield: “In most social interactions whites get to be seen as individuals. Racial minorities, by contrast, become aware from a young age that people will often judge them as members of their group, and treat them in accordance with the (usually negative) stereotypes attached to that group.” (Mounk, 2018, p. 202) Perhaps that is why one book keeps leaping to mind during these times, Mihail Sebastian’s Journal: 1935-1944, though it was written in very different circumstances. Radu Ioanid in his introduction writes: “One of Sebastian’s fundamental choices was to consider himself a Romanian rather than a Jew, a natural decision for one whose spirit and intellectual production belonged to Romanian culture. He soon discovered with surprise and pain that this was an illusion: both his intellectual benefactor and his friends ultimately rejected him only because he was Jewish.” (Sebastian, 2000, p. xii)

When the entries in this journal begin, Sebastian is in his late twenties. His life is full of literary feuds, theater going, agonies over his work, women chasing him and women he chases, and his passion for music, music, music. There are Mozart sonatas on the radio, plans to go skiing, lovely descriptions of his “amatory sufferings,” intelligent reading of Proust. He often meets and dines and parties with friends. But as the Germans pick up steam, the anti-Semites in Romania are emboldened; because he is Jewish he’s no longer allowed to practice law, the plays he writes are not produced, he loses his job with the Writer’s Association, he has no money to pay the rent and soon he’s not allowed to live in his apartment anyhow. Read more »

by Guy Elgat

Recently, CNN sent their reporter to cover yet another Trump rally (in Pennsylvania), but this time reporter Gary Tuchman was assigned the more specific task of interviewing Trump supporters who were carrying signs or large cardboard cut-outs of the letter “Q” and wearing T-shirts proclaiming “We are Q”.[1] These Trump supporters were professing their belief in the existence of a person known as Q or QAnon who is supposed to be an anonymous, high-level activist who works from inside the administration with the goal of supporting Trump’s agenda by squashing “deep-state” anti-Trump forces and removing any other obstacle that might stand in the way of consummating the President’s revolutionary vision.

Recently, CNN sent their reporter to cover yet another Trump rally (in Pennsylvania), but this time reporter Gary Tuchman was assigned the more specific task of interviewing Trump supporters who were carrying signs or large cardboard cut-outs of the letter “Q” and wearing T-shirts proclaiming “We are Q”.[1] These Trump supporters were professing their belief in the existence of a person known as Q or QAnon who is supposed to be an anonymous, high-level activist who works from inside the administration with the goal of supporting Trump’s agenda by squashing “deep-state” anti-Trump forces and removing any other obstacle that might stand in the way of consummating the President’s revolutionary vision.

At one point in the interview, in his attempt to probe the beliefs of the Q-ers, as I shall call them, Gary Tuchman challenged one of them and said: “So you don’t have any proof [that Q exists] but that’s what you’re guessing”, in response to which the interviewee said “and you don’t have any proof there isn’t”. In another exchange Tuchman again tried to interrogate a Q-er about her beliefs, saying “Maybe it is not true [that Q exists] because there is no evidence of it…”, in response to which the interviewee shot back: “There hasn’t been any non-evidence yet”.

Upon hearing these retorts many might react with a baffled scoff and dismiss them as not worthy of taking seriously. But though this reaction is at the end of the day warranted – or so I shall argue – it is hard, though important, to explain exactly what is wrong with the Q-ers’ response and why Q-ers might think that it serves their purpose and is thus perfectly legitimate. As we shall see, once we start to reflect on these questions we will find ourselves pretty quickly knee-deep in philosophy, what will bring out again the importance and relevance of philosophy to our everyday lives. Read more »

I call you Quantum Angel

because you’re so unbelievable

not even physicists can pin you down,

the way you flit through atoms

you must have wings,

the way you punk time

your wings must be turbocharged,

the way you fling particles

we can’t keep up—

where do you get so many

tiny spinning things?

you must have a secret source

or you’re a maestro of illusion

a tall-tale provider, a teller

who tells in sparks and quarks

the most fundamental things

(mere things, almost)

in super hadron mist

colliders

Jim Culleny

9/9/18

—Drawing: Quantum Angel

Jim C., 1997

by Shawn Crawford

Make it one for my baby, and one more for the road—Arlen/Mercer

On the 4th of July, the kids start acting jakey once the sun approaches the tree line. It’s maybe, kinda, sorta, starting to get dark, so shouldn’t we break out the fireworks? No. But soon you’ll relent and allow some preliminaries, like rockets that eject a little plastic soldier attached to a parachute, which are fun to watch, and the kids chase them around the golf course across the street and try to catch them before they reach the ground.

I sit outside at my uncle’s house and watch everyone, enjoying the cool breeze that has no business showing up on a July day in Kansas. My parents have decided to stay in Colorado all summer, to escape the heat that hasn’t shown up yet, so we’re next door at my uncle’s. My father and his brother have lived adjacent or across the street from each other for well over half their adult lives.

All the cousins have made the trip, including S. and her husband H., missionaries in the Philippines and home on furlough. I sit and listen to their very earnest talk about The Spirit and The Heart and Salvation and going out into The Fields. None of them would claim the title of Baptist anymore, the religion of my youth. They have all joined the ranks of Mega-Church Evangelicals, proclaiming their triumph over petty denominations for a purer form of Christianity. One that skews very white, very affluent, but includes a coffee shop in the Gathering Space of the church-cum-warehouse to demonstrate their welcoming nature and hipness.

In a time not that long ago, I would have joined right in, enjoying the discussion and the parsing of scripture, and debating the theology of even the most mundane of choices. But now it sets my nerves on edge and makes me irritable, especially with the Christian radio station blaring throughout the house and on the patio, every song reaching the same easy solution. Finally, I just tune it all out. Read more »

by Samia Altaf

In the 1960s, in the sleepy little city of Sialkot, almost in no-man’s land between India and Pakistan and of little significance except for its large cantonment and its factories of surgical instruments and sports goods, there were two cinema houses, all within a mile of our house, No. 3 Kutchery Road. Well three to be exact, the third being an improvisation involving two tree trunks with a white sheet slung between them at the Services club and only on Saturday nights.

In the 1960s, in the sleepy little city of Sialkot, almost in no-man’s land between India and Pakistan and of little significance except for its large cantonment and its factories of surgical instruments and sports goods, there were two cinema houses, all within a mile of our house, No. 3 Kutchery Road. Well three to be exact, the third being an improvisation involving two tree trunks with a white sheet slung between them at the Services club and only on Saturday nights.

The one closest to us our house, just this side of the railway crossing, was Nishat, popularly known as Begum’s cinema with a risqué aura because it was owned and managed by the ‘Begum,’ a burqa-clad, not so young, but still beautiful woman. There was hushed talk about the Begum’s morals because she, a single woman, owned and managed a cinema house in a time when so-called ‘decent’ women rarely went to the cinema let alone own one.

The second, past the railway crossing on the other side of the ‘drumma wallah chowk,’ the main city square, was the Lalazar. Lalazar was considered to be in a class above the others partly for its sweeping marble staircase curving upwards to the gallery and partly for its owner Mr. Majeed’s newly acquired daughter-in-law Mussarat Nazir, the rustic Punjabi beauty and a leading lady of film industry. Mr. Majeed, a portly gentleman with a loud laugh, was among the city fathers, the ‘shurafa,’ of the city. Mussarat Nazeer, still in her teens, came to public attention in the movie Yakkey Wali. My father tells how he and his friends, all grown and married men, saw that movie about twenty times and every time M. Nazir appeared on screen, they along with the whole house threw coins at the screen in the age old tradition of showing one’s appreciation. M. Nazir’s untimely departure at the height of her career to lead a life of married bliss in Canada was mourned by all till she returned thirty years later, still the rustic beauty, and became a household name selling millions of audio cassettes of Punjabi wedding and folk songs. My older son, then three years old, heard her signature folk song ‘Laung gwacha,’ saw her face on the grimy cover of a much used audio cassette, fell immediately in love and vowed to marry her. His grandfather understood completely. Read more »

by Abigail Akavia

Would I rather go deaf or blind? Every once in a while, I come back to this question in some version or another. Say I had to choose which sense I’d lose in my old age, which would it be? I always give myself, unequivocally, the same answer: I’d rather go blind. I’d rather my world go darker than quieter. I imagine it as a choice between seeing the world and communicating with it; in this hypothetical, communication with the world is all-encompassing, its loss more devastating than the loss of sight. It is perhaps clear from the mere fact that I pose this question that I do not live with a disability involving the senses. Individuals who are vision- or hearing-impaired would have an entirely different take on this question and on the issues I raise below, but hopefully what I write here will go beyond stating my own prejudices.

Would I rather go deaf or blind? Every once in a while, I come back to this question in some version or another. Say I had to choose which sense I’d lose in my old age, which would it be? I always give myself, unequivocally, the same answer: I’d rather go blind. I’d rather my world go darker than quieter. I imagine it as a choice between seeing the world and communicating with it; in this hypothetical, communication with the world is all-encompassing, its loss more devastating than the loss of sight. It is perhaps clear from the mere fact that I pose this question that I do not live with a disability involving the senses. Individuals who are vision- or hearing-impaired would have an entirely different take on this question and on the issues I raise below, but hopefully what I write here will go beyond stating my own prejudices.

To prefer sound over sight is by no means an obvious choice. One could say that a preference for sound over sight goes against millennia of Platonic thought, which prioritizes sight as giving us access to what is stable, verifiable, graspable to the mind’s eye: the idea is literally that which is seen (from id-, one of the Greek roots for to see). Sound, on the other hand, changes in time, it is fleeting, untrustworthy, and hence inferior.

But poetry and myth have offered an alternative way of thought. Ancient myth is populated by sage blind men like the prophet Tiresias and Oedipus (after, of course, he learns the truth about his identity). Their lack of physical sight is not only a counterpart to their exceptional insight into the way of the world but, to an extent, the very source of their intellectual and spiritual advantage. In the case of both, what they lack in perception they make up for in a remarkable facility with language. Tiresias’ advantage over his seeing adversaries is perhaps the better-known example, as he delivers truthful but irritatingly cryptic prophetic messages to Oedipus (in Sophocles’ Oedipus the King) and Creon (in Antigone). Managing to confuse and manipulate them, Tiresias has the rhetorical upper hand, and the audience always already knows that he is in the right. In Oedipus at Colonus, the last play Sophocles wrote, the old Oedipus turns up as a similarly prophetic, wrathful speaker of harsh truths, with a sharp ability to pick out the dissimulators from the honest ones around him by virtue of what they say. Neither man’s ability to communicate is lessened by their blindness; in fact, it allows them to recognize and speak the truth more easily. Read more »

by Joseph Shieber

The German philosopher Albrecht Wellmer died earlier this month in Berlin, on September 13 at the age of 85.

The German philosopher Albrecht Wellmer died earlier this month in Berlin, on September 13 at the age of 85.

A member of the “second generation” of the Frankfurt School, Wellmer was a Ph.D. student of Adorno’s, a professorial assistant of Habermas’s, and a colleague of Arendt’s.

Although Wellmer wrote both of his dissertions (the Promotionsschrift and the Habilitationsschrift) on topics in the philosophy of science, he soon turned to ethics and critical theory, and later to the study of the philosophy of language and the philosophy of music. He held positions as a professor at the New School for Social Research, the Universität Konstanz, and the Freie Universität Berlin. In 2006, he was awarded the Theodor Adorno Prize by the city of Frankfurt.

Infinitely less significant is that Wellmer also gave me my first job in philosophy, as a wissenschaftlicher Hilfsassistent — basically a teaching assistant — in the Institute for Hermeneutics in the philosophy department at the Free University of Berlin. I worked under him from 1994 to 1997, including serving as a teaching assistant for the lectures that were published in 2004 as Sprachphilosophie: Eine Vorlesung. Read more »

by Thomas R. Wells

The idea of ‘good corporate citizenship’ has become popular recently among business ethicists and corporate leaders. You may have noticed its appearance on corporate websites and CEO speeches. But what does it mean and does it matter? Is it any more than a new species of public relations flimflam to set beside terms like ‘corporate social responsibility’ and the ‘triple bottom line’? Is it just a metaphor?

The idea of ‘good corporate citizenship’ has become popular recently among business ethicists and corporate leaders. You may have noticed its appearance on corporate websites and CEO speeches. But what does it mean and does it matter? Is it any more than a new species of public relations flimflam to set beside terms like ‘corporate social responsibility’ and the ‘triple bottom line’? Is it just a metaphor?

The history of the term does not promise much. It does indeed seem to have evolved out of corporate speak – how corporations represent themselves rather than how they view themselves – selected, perhaps, for sounding reassuring but vague. Its popularity has far preceded its definition; ‘corporate citizenship’ is still evolving, looking for a place to settle.

But what it is about is important. For it represents a political turn to the old question, Who are corporations for and how is their power to be managed? Are corporations bound to serve society’s interest, or are they free to follow their own? Are they public institutions, part of the governance of our society and publicly accountable to us for their actions, or are they private associations accountable only to their managers and owners?

For around a hundred years this question had an institutional answer in the form of ‘managed capitalism’, with governments playing a central role in corporate decision-making. They were outright owners of many businesses; they directed negotiations with labour – itself institutionally empowered by the state as a countervailing power to the large corporation; and they used the wide discretionary authority of the state to cajole and coerce company directors to serve what they saw as the public interest. Read more »

by Emrys Westacott

Learning Objectives. Measurable Outcomes. These are among the buzziest of buzz words in current debates about education. And that discordant groaning noise you can hear around many academic departments is the sound of recalcitrant faculty, following orders from on high, unenthusiastically inserting learning objectives (henceforth LOs) and measurable outcomes (hereafter MOs) into already bloated syllabi or program assessment instruments.

Learning Objectives. Measurable Outcomes. These are among the buzziest of buzz words in current debates about education. And that discordant groaning noise you can hear around many academic departments is the sound of recalcitrant faculty, following orders from on high, unenthusiastically inserting learning objectives (henceforth LOs) and measurable outcomes (hereafter MOs) into already bloated syllabi or program assessment instruments.

But why do they moan and groan? Administrators, accreditors, and politicians see no problem. Nor do many teachers in STEM subjects and other technical fields. And prima facie they have a good case. Isn’t it obviously a good idea to have LOs for any course you teach? And shouldn’t you know what they are, be able to articulate them, and let your students know what you want them to achieve? How could any reasonable person think otherwise?

Ditto for MOs. Don’t you want to know if your LOs have been achieved? Why on earth wouldn’t you want to know? This, surely, is how we improve on what we do. We set goals. We see how well we are meeting them. We then tinker, tweak, or revamp wholesale in light of our findings, in a never-ending process of improvement.

It all sounds so sensible.

But what is sound practice in some contexts makes much less sense in others. Even those who have drunk the LO-MO Kool-Aid might balk at the idea of couples specifying in their pre-nuptial agreements a well-defined set of marital objectives linked to measurable outcomes. When it comes to college courses, the emphasis on LOs and MOs may sometimes be reasonable, particularly in courses that form an integrated and progressive program of study in technical subjects that lend themselves to exact modes of assessment. But I suspect they are of dubious value in at least one common and important kind of course–namely, the general education course where most of the students are receiving their only college-level exposure to an academic field. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Carl Pierer

In the first part of this essay, the axiom of choice was introduced and a rather counterintuitive consequence was shown: the Banach-Tarski Paradox. To recapitulate: the axiom of choice states that, given any collection of non-empty sets, it is possible to choose exactly one element from each of them. This is uncontroversial in the case where the collection is finite. Simply list all the sets and then pick an element from each. Yet, as soon as we consider infinite collections, matters get more complicated. We cannot explicitly write down which element to pick, so we need to give a principled method of choosing. In some cases, this might be straightforward. For example, take an infinite collection of non-empty subsets of the natural numbers. Any such set will contain a least element. Thus, if we pick the least element from each of these sets, we have given a principled method. However, with an infinite collection of non-empty subsets of the real numbers, this particular method does not work. Moreover, there is no obvious alternative principled method. The axiom of choice then states that nonetheless such a method exists, although we do not know it. The axiom of choice entails the Banach-Tarski Paradox, which states that we can break up a ball into 8 pieces, take 4 of them, rotate them around and put them back together to get back the original ball. We can do the same thing with the remaining 4 pieces and get another ball of exactly the same size. This allows us to duplicate the ball.

The second part of this essay demonstrated a useful consequence (or indeed, an equivalent) of the axiom of choice, known as Zorn’s Lemma and looked at a few applications of this Lemma. Two positions have been mapped out in the course of this essay. On the one hand, the axiom has very counterintuitive consequences, so much so that they’ve received the name of a paradox. On the other hand, the axiom proves to be very useful in deducing mathematical propositions. These considerations lead back to the question that had already been raised at the end of the first part: how are we to decide on the status of an axiom, on whether to accept it or reject it?

In this third and final part of the essay, we will take a more philosophical approach to this problem. In particular, we will look at a possible resolution offered by Penelope Maddy in her Defending the Axioms. The solution offered would lead onto further questions about the nature of mathematics: what is mathematics actually about? At the same time, Maddy’s view is based on a certain conception of proof that does not really reflect mathematical practice. The essay, due to limitations, only hints at a different perspective offered by looking at what mathematicians actually do and what role proofs play for them. Read more »

by Tamuira Reid

It’s nearing lunchtime when I make it over to Kevin’s, and beautiful out, but his window shades are still drawn closed, outside light on. I notice the porch slopes ever so slightly to the right, where a few forgotten footballs and beer bottles have now collected. I knock. Wait. Hear some movement and bustling. Then silence. I knock again. Silver masking tape covers large rips in the screen door, big enough for a head to push through. More movement. Finally Kevin emerges, a cigarette hanging from his lips.

He doesn’t say hi, but rather ushers me in, a quick gesture of his skinny body, a bony hand-to-back motion that says hurry.

I am used to this with Kevin. The hurry up and go of it all. When you’ve made the conscious decision to hangout with crystal meth addicts, life becomes a constant hurry-up-and- go, even if you’re only going to the bathroom.

I like Kevin. He’s thoughtful and smart and ridiculously resourceful. He’s also one of the worst addicts I’ve come across during my time in Clatsop County – or in my personal life – which is saying a lot. He will likely never get clean. He might commit more than a few crimes. And he will probably die too young. His life is already pedal to the metal, as he’d tell you. Pedal to the fucking metal. Read more »

by Dwight Furrow

Although frequently lampooned as over-the-top, there is a history of describing wines as if they expressed personality traits or emotions, despite the fact that wine is not a psychological agent and could not literally have these characteristics—wines are described as aggressive, sensual, fierce, languorous, angry, dignified, brooding, joyful, bombastic, tense or calm, etc. Is there a foundation to these descriptions or are they just arbitrary flights of fancy?

Although frequently lampooned as over-the-top, there is a history of describing wines as if they expressed personality traits or emotions, despite the fact that wine is not a psychological agent and could not literally have these characteristics—wines are described as aggressive, sensual, fierce, languorous, angry, dignified, brooding, joyful, bombastic, tense or calm, etc. Is there a foundation to these descriptions or are they just arbitrary flights of fancy?

Last month on this blog I argued that recent work in psychology that employs “vitality forms” helps us understand how music expresses emotion. Will vitality forms help us understand how wine could express feeling states or personality characteristics?

Vitality forms are “the flow pattern” of human experience, “the subjectively experienced shifts in the internal states” that characterize sensations, thoughts, actions, emotions, and other feeling states. Discovered by Daniel Stern and described in his 2010 book Forms of Vitality: Exploring Dynamic Experience in Psychology, the Arts, Psychotherapy, and Development, vitality forms constitute the temporal structure of experience, the duration, acceleration and intensity of an experience. Importantly, vitality forms are not tied to a specific sense modality. All five senses as well as thoughts and feelings exhibit vitality forms. “A thought can rush onto the mental stage and swell, or it can quietly just appear and then fade”, as Stern notes. So can sounds, visual experiences, tactile impressions or emotions—anger can explode or emerge as a slow burn. In short, a vitality form is how any conscious experience emerges and changes over time. Read more »

by Michael Liss

He flew so fast and so close to the sun that it took an entire lifetime to fall back to Earth.

He flew so fast and so close to the sun that it took an entire lifetime to fall back to Earth.

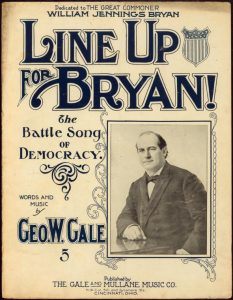

William Jennings Bryan was just 36 years old when, on July 9, 1896, he seized the Democratic Party’s Presidential nomination on the back of a single, electrifying speech, “Cross of Gold.”

Twenty-nine years later almost to the day, a haunted shell of his former self, he sat at the prosecution’s table, waiting for opening arguments in the Scopes Monkey Trial, unaware it would lead to his humiliation and ultimately hasten his tragic end.

In between, “The Great Commoner” was nominated twice more by his party, in 1900 and 1908, and served as Woodrow Wilson’s Secretary of State from 1913 to 1915. He then threw himself into efforts for causes as diverse as women’s suffrage, direct elections for Senators, and Prohibition. In the 1920s, he shifted his primary focus to his faith, but remained a prominent figure among Democrats through the 1924 Convention, when he was literally heckled off the stage in tears while trying to broker a compromise on an anti-KKK platform plank.

Bryan is an enigma. He failed frequently, but got multiple chances where abler men were passed over. Contemporaries questioned his intelligence and the scope of his interests, yet the exacting, often arrogant Wilson put him in his Cabinet and gave him a free hand with Latin American policy. His durability might best be ascribed to his possession of two tremendous assets: First, he was arguably the best orator of his time, compelling almost whenever and wherever he spoke, and, second, he seemed to have a psychic bond with his base. As the historian Richard Hofstadter noted, while other politicians of that era may have sensed the feelings of the people, Bryan embodied them. His people stayed with him through his successes and his disappointments. Read more »