by Thomas Manuel

According to Oxfam, “82 percent of the wealth generated last year went to the richest one percent of the global population, while 3.7 billion people that account for the poorest half of the world saw no increase in their wealth.” In the US, the top 1% of families own more wealth than the bottom 95%. In India, 73% of the wealth generated in 2017 went to the richest 1% while the bottom 50% got a measly 1% of that wealth. To combat these inequalities, we’ll have to upend or at least leverage the fundamental logic at the heart of capitalism that wealth breeds greater wealth so that it works for the benefit of the poor. One proposed solution that is gaining some mainstream attention is the idea of social wealth funds.

Social wealth funds are essentially publicly-owned financial funds that hold income-generating assets and use the returns for the welfare of all. They offer one way of socializing and redistributing wealth. Probably the most famous and most ambitious proposal for social wealth fund is the one commonly called the Meidner Plan. Implemented in the 1980s, these funds were called “wage-earner funds” and were an attempt to create a system that would slowly transfer ownership of companies from their shareholders to their employees. It worked by mandating that large firms had to issue new shares worth 20% of the annual profit to these wage-earner funds which were maintained by trade unions. This stock could not be sold and the dividend from these stocks would be reinvested into more stock. As per the original estimate, the majority of the ownership of Swedish companies could pass to employees within 25 years. But while the Meidner Plan was tried out, a successive government shut it down. Read more »

I write this as Saturday begins to wane on the long Columbus Day weekend while I listen on the radio to the speeches given by senator after senator prior to the final confirmation vote for Bret Kavanaugh as Associate Justice on the Supreme Court of the United States of America. The vote is scheduled for 3.30 p.m. October 6, 2016. I listen to their conflicted words in the Senate of the United States pleading yes or no, or yes and no. Conjuring images, I am reminded of that Roman mythology and the artists’ rendition of it, of the Rape of the Sabine Women.

I write this as Saturday begins to wane on the long Columbus Day weekend while I listen on the radio to the speeches given by senator after senator prior to the final confirmation vote for Bret Kavanaugh as Associate Justice on the Supreme Court of the United States of America. The vote is scheduled for 3.30 p.m. October 6, 2016. I listen to their conflicted words in the Senate of the United States pleading yes or no, or yes and no. Conjuring images, I am reminded of that Roman mythology and the artists’ rendition of it, of the Rape of the Sabine Women.

My

My

Every October there’s a huge book fair in my town, where used books donated by the community are put up for sale in a large hall at the fairgrounds. It’s no exaggeration to say that it’s a high point of my year.

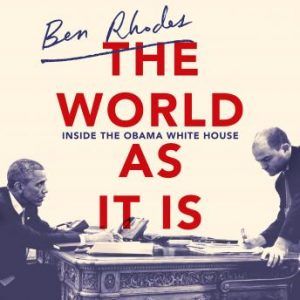

Every October there’s a huge book fair in my town, where used books donated by the community are put up for sale in a large hall at the fairgrounds. It’s no exaggeration to say that it’s a high point of my year. As the first African American president of the United States (US), Barack Obama is a uniquely historical personality. Each of us has our opinions, or will formulate opinions, as to the success or limitations of his eight years in office as a Democratic president from 2009-2017, and as to the person who is Obama. Helping us in the formulation of our views on Obama and his presidency, is Ben Rhodes book, The World As It Is: Inside the Obama White House.

As the first African American president of the United States (US), Barack Obama is a uniquely historical personality. Each of us has our opinions, or will formulate opinions, as to the success or limitations of his eight years in office as a Democratic president from 2009-2017, and as to the person who is Obama. Helping us in the formulation of our views on Obama and his presidency, is Ben Rhodes book, The World As It Is: Inside the Obama White House.  One of the most simple, elegant and powerful formulations of the conflict between science and religion is the following bit of reasoning. ‘Faith’ is belief in the absence of evidence; science demands that beliefs are always grounded in evidence. Therefore, the two are mutually exclusive. This is an oft-repeated argument by modern atheists, and it connects different aspects of what is usually called the ‘Conflict Thesis’: the idea that science and religion are opposed to each other not just now, but always and necessarily.

One of the most simple, elegant and powerful formulations of the conflict between science and religion is the following bit of reasoning. ‘Faith’ is belief in the absence of evidence; science demands that beliefs are always grounded in evidence. Therefore, the two are mutually exclusive. This is an oft-repeated argument by modern atheists, and it connects different aspects of what is usually called the ‘Conflict Thesis’: the idea that science and religion are opposed to each other not just now, but always and necessarily. In the Mood for Love

In the Mood for Love