by Joshua Wilbur

Repetition, in itself, is neither good nor bad. Everything repeats. “Nature is an endless combination and repetition of very few laws,” said Emerson. Seasons come, and seasons go.

But what’s true for seasons isn’t true for people. We tend to prefer some forms of repetition to others. At its best, repetition is a great source of comfort and a precondition for mastering any task. The familiar rhythms of the Sunday church service are a balm to many, and it takes years of practice to throw a 98 mile-per-hour fastball that cuts in on a hitter’s hands at just the right moment.

At its worst, repetition means monotony and aimless toil: Sisyphus pushing his boulder up the hill for all eternity. Freud wrote of our “compulsion to repeat” the past, sensing that reenactment lies at the heart of everyday neuroticism, psychological trauma, and the most unnerving displays of madness—“All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy,” writes Jack Torrance, a thousand times over, in The Shining.

In between these two extremes—between the master and the madman—repetition provides the unglamorous but necessary foundation of daily life. It’s the soundtrack of childhood: brush your teeth, tie your shoes, finish your homework, eat your dinner, and so on. By the time a person reaches adulthood, she has internalized an incalculable number of habits: some good, some bad, but most avoiding the sureness of a positive or negative judgement. Thanks to our neurological adaptiveness, we are constantly slipping into patterns without realizing it, and the unrelenting expansion of consumer tech has only opened more avenues for our habitual instincts. Read more »

It could almost be a question on a very meta personality quiz: Do you prefer the Myers-Briggs typology or the Big Five personality traits? The Myers-Brigg Type Inventory is a popular tool that was developed outside of the scientific establishment by two women who did not have credentials in psychology. It’s qualitative rather than quantitative, and in the past decade or so, it’s been criticized as meaningless or unscientific. The Big Five taxonomy is widely accepted in academia and is the basis of much current personality research. It’s quantitative; in fact, it’s based on statistical analysis. Am I rejecting science if I continue to prefer the Myers-Briggs system as a key to understanding my own personality and those of others?

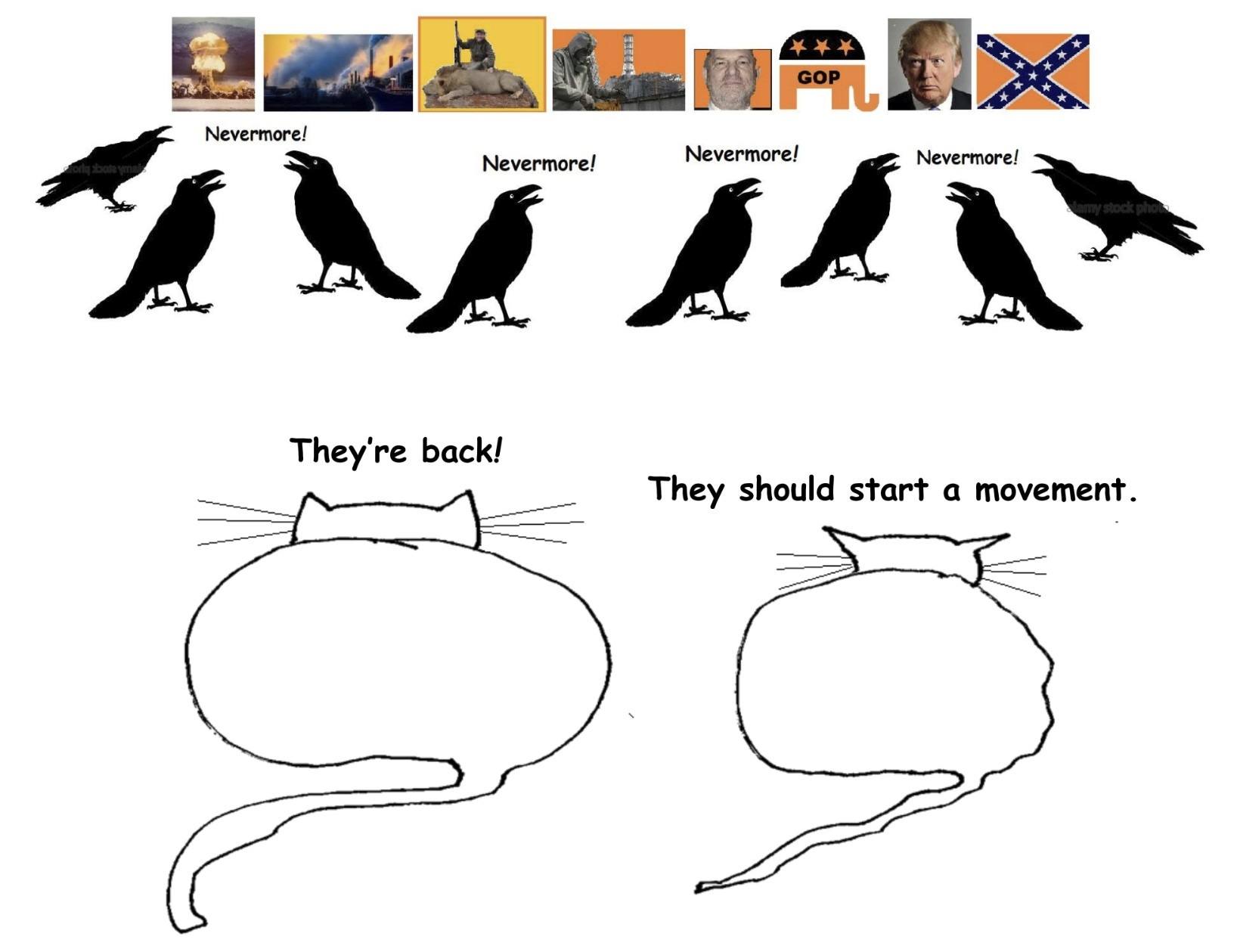

It could almost be a question on a very meta personality quiz: Do you prefer the Myers-Briggs typology or the Big Five personality traits? The Myers-Brigg Type Inventory is a popular tool that was developed outside of the scientific establishment by two women who did not have credentials in psychology. It’s qualitative rather than quantitative, and in the past decade or so, it’s been criticized as meaningless or unscientific. The Big Five taxonomy is widely accepted in academia and is the basis of much current personality research. It’s quantitative; in fact, it’s based on statistical analysis. Am I rejecting science if I continue to prefer the Myers-Briggs system as a key to understanding my own personality and those of others? It is difficult to remember a time over recent decades when a president of the United States (US) has created so much controversy and division within the US and challenged its credibility and standing in international relations as has the incumbent president, Donald Trump. Indeed, so bewildering to many is the election of a former reality TV star and dubious businessman without experience in government, to the high office of president of the US and ‘leader’ of the ‘free’ world, a plethora of literature to account for such a phenomenon has emerged. Similarly, commentaries on evaluations of Trump’s calibre and character, and just how far he is fit for such high office and powerful position in global politics, are plentiful. Jon Meacham’s The Soul of America: The Battle for Our Better Angels can be viewed as a contribution to the literature on those issues.

It is difficult to remember a time over recent decades when a president of the United States (US) has created so much controversy and division within the US and challenged its credibility and standing in international relations as has the incumbent president, Donald Trump. Indeed, so bewildering to many is the election of a former reality TV star and dubious businessman without experience in government, to the high office of president of the US and ‘leader’ of the ‘free’ world, a plethora of literature to account for such a phenomenon has emerged. Similarly, commentaries on evaluations of Trump’s calibre and character, and just how far he is fit for such high office and powerful position in global politics, are plentiful. Jon Meacham’s The Soul of America: The Battle for Our Better Angels can be viewed as a contribution to the literature on those issues.

Last fall, after a day spent hiking around the neighborhood, I ended up back on my porch with my buddy, Chef Mike. We were drinking beers and chatting about life.

Last fall, after a day spent hiking around the neighborhood, I ended up back on my porch with my buddy, Chef Mike. We were drinking beers and chatting about life. The William Penn High School Marching band was a juggernaut, the coolest team in school. Its director, Holman F James, strode the football field, unzipped windbreaker, cigarette dangling, the Greatest Generation’s bandmaster. A sterling musician, he played trumpet and piano, wrote or arranged all the music and choreographed our field shows. He was also a solider, avid outdoorsman and master craftsman, everything Hugh Hefner should have been.

The William Penn High School Marching band was a juggernaut, the coolest team in school. Its director, Holman F James, strode the football field, unzipped windbreaker, cigarette dangling, the Greatest Generation’s bandmaster. A sterling musician, he played trumpet and piano, wrote or arranged all the music and choreographed our field shows. He was also a solider, avid outdoorsman and master craftsman, everything Hugh Hefner should have been.

A bit of self indulgence – also a kind of preface to all the 3 Quarks Daily

A bit of self indulgence – also a kind of preface to all the 3 Quarks Daily

1. Bored, and with little to occupy their time, two cousins, Elsie, who was 16, and Frances, who was 10, decided to play around with photography. At a river near where they lived, they manipulated an image so that it looked as if they were interacting with little, magical winged creatures — fairies.

1. Bored, and with little to occupy their time, two cousins, Elsie, who was 16, and Frances, who was 10, decided to play around with photography. At a river near where they lived, they manipulated an image so that it looked as if they were interacting with little, magical winged creatures — fairies.

Two weeks ago, Maniza Naqvi evocatively wrote here on the resonance of a mythological rape in the eventual confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh to the US Supreme Court (

Two weeks ago, Maniza Naqvi evocatively wrote here on the resonance of a mythological rape in the eventual confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh to the US Supreme Court ( Middle age brings sometimes uncomfortable self-reflection. One thing I have realized is that I am not a particularly good person. Not evil, just mediocre. Lots of people are much better at morality than me, including many of my students. On the other hand, I am quite good at the academic subject of ethics. Good enough to teach it at a university and write papers that occasionally appear in nice journals.

Middle age brings sometimes uncomfortable self-reflection. One thing I have realized is that I am not a particularly good person. Not evil, just mediocre. Lots of people are much better at morality than me, including many of my students. On the other hand, I am quite good at the academic subject of ethics. Good enough to teach it at a university and write papers that occasionally appear in nice journals.

How conceivable is this? Trump loses the 2020 US presidential election. But he refuses to concede, claiming that results in the swing states of Ohio and Florida were invalid due to voter fraud and crooked election officials. Fox News, other right-wing media and the Republican controlled congress go along with this. So Trump remains president until, in the words of Senate leader Mitch McConnell, “we are able to clear up this mess.” Clearing up the mess, it turns out, could take some time–even longer than it takes for Trump to fulfill his promise to release his tax returns. Law suits are brought, but guess what? By a 5 to 4 majority, the supreme court refuses to hear them.

How conceivable is this? Trump loses the 2020 US presidential election. But he refuses to concede, claiming that results in the swing states of Ohio and Florida were invalid due to voter fraud and crooked election officials. Fox News, other right-wing media and the Republican controlled congress go along with this. So Trump remains president until, in the words of Senate leader Mitch McConnell, “we are able to clear up this mess.” Clearing up the mess, it turns out, could take some time–even longer than it takes for Trump to fulfill his promise to release his tax returns. Law suits are brought, but guess what? By a 5 to 4 majority, the supreme court refuses to hear them. Although wine writing takes diverse forms, wine evaluation is a persistent theme of much wine writing. When particular wines, wineries or vintages are under discussion, at some point the writer will typically turn to assessing wine quality. The major publications devoted to wine include tasting notes that not only describe a wine but indicate its quality, often with the help of a numerical score, and most wine blogs and online wine magazines include a wine evaluation component that is central to their mission.

Although wine writing takes diverse forms, wine evaluation is a persistent theme of much wine writing. When particular wines, wineries or vintages are under discussion, at some point the writer will typically turn to assessing wine quality. The major publications devoted to wine include tasting notes that not only describe a wine but indicate its quality, often with the help of a numerical score, and most wine blogs and online wine magazines include a wine evaluation component that is central to their mission.