Fujiko Nakaya. Fog x FLO at Arnold Arboretum, Boston, MA. August 2018.

Digital photograph by Sughra Raza, August 21, 2018.

Visit here.

Though we are an aggregator blog (providing links to content elsewhere) on all other days, on Mondays we have only original writing by our editors and guest columnists. Each of us writes on any subject we wish, and the length of articles generally varies between 1000 and 2500 words. Our writers are free to express their own opinions and we do not censor them in any way. Sometimes we agree with them and sometimes we don’t.Below you will find links to all our past Monday columns, in alphabetical order by last name of the author. Within each columnist’s listing, the entries are mostly in reverse-chronological order (most recent first).

by Joseph Shieber

The controversy over the hiring of Sarah Jeong by the New York Times has largely subsided. However, we can still learn some important lessons from the discussion of Jeong’s social media posts that were – depending on your perspective – cases of either ironic troll-trolling or of anti-white racist speech.

The controversy over the hiring of Sarah Jeong by the New York Times has largely subsided. However, we can still learn some important lessons from the discussion of Jeong’s social media posts that were – depending on your perspective – cases of either ironic troll-trolling or of anti-white racist speech.

Jeong’s hiring came close on the heels of another controversy, sparked by an apology by the editors of The Nation for a poem by Anders Carlson-Wee, a young white man who wrote in African American vernacular and employed ableist imagery. While critics of the magazine from the left decried the tone-deafness of the poem, critics on the right took the magazine’s editors to task for silencing the poet.

Since I’m gearing up for a fall semester in which I’ll be offering a course on the philosophy of language, the juxtaposition of the two controversies was particularly striking for me. In particular, I want to examine the way that two prominent conservative critics reacted to the controversies and show how their responses reveal a glaring lack of understanding of how language works. Read more »

by Samia Altaf

“This girl will never be able to find a husband,” declared Baiji, big mother, my maternal grandmother, soon after she took her first look at me.

“Hai hai,” she almost beat her chest, “look at her, just look.” She points at me holding herself back as if from a contaminant, appealing to the women — assorted aunts and cousins milling around, who hid their faces in their chadors and shook their heads — “her nose is too big, her eyes too small, she is bald.”

“And worst of all, hai hai,” — here Baiji’s voice drops ominously and a trembling hand goes to cover her mouth at the horror of it — “her color! It is not… not…not fair. It is… quite dark.”

She looks pityingly at my mother standing beside her in all her Kashmiri “fairness” and youthful glory — my mother of the fairest, luminous, skin that she took intact and unlined to her grave seven decades later — and puts a loving hand on her head. “My poor daughter… what a fate for you, hai hai. Well, at least these genes have not come from your side of the family.” (One of the aunts present at the occasion swears Baiji said germs and not genes.)

Baiji might as well have added, while on the roll, that the girl is also toothless and incontinent for I was all of a year old. Read more »

by Thomas R. Wells

The main job of ‘culture’ in a modern society seems to be shielding people from the demands of morality. In its intellectual role it justifies inequality between citizens. In its national history role it gives citizens a delusional sense of their country’s significance and entitlement, followed by a dangerous sense of grievance when this isn’t sufficiently recognised by the rest of the world. In its identitarian role it deflects demands for justification into mere proclamations of fact: ‘Why do we do this or that awful thing?… Because shut up. It is who we are.’

The main job of ‘culture’ in a modern society seems to be shielding people from the demands of morality. In its intellectual role it justifies inequality between citizens. In its national history role it gives citizens a delusional sense of their country’s significance and entitlement, followed by a dangerous sense of grievance when this isn’t sufficiently recognised by the rest of the world. In its identitarian role it deflects demands for justification into mere proclamations of fact: ‘Why do we do this or that awful thing?… Because shut up. It is who we are.’

None of these ideas of culture is worth keeping. We should throw them all out and focus on a different idea of culture as integration in a social world, and of a cultured person as one who can hear and speak to many worlds.

I

First there is there is the idea of culture as a moral hierarchy between citizens. Individuals are supposed to strive to become better, more civilised people. Which turns out to mean, not better at being good people; not better at making and living up to ethical judgements, such as our obligations to the less fortunate. Rather, it means becoming a connoisseur of certain arcane and unpopular art forms.

Familiarity with opera, for instance, largely functions as a compass for orienting the socio-economic class structure between the civilised and the rest. Most people who attend opera performances do so as a performance of their class identity, not for genuine aesthetic delight. They have at best a superficial aesthetic appreciation of what is going on. This can be seen in their reliance on a handful of classic brands which substitute for independent taste or judgement. See for example the dominance of the odious Wagner, the Manchester United of opera. The best explanation of the popularity of opera among the upper classes is that it happens to be absurdly expensive and difficult to enjoy and therefore functions as a good – difficult to fake – signal of who is in the club. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Emrys Westacott

On July 5 The Nation published a 14 line poem by Anders Carlson-Wee entitled “How-To.” The speaker in the poem is giving advice on how to beg. The poem begins:

On July 5 The Nation published a 14 line poem by Anders Carlson-Wee entitled “How-To.” The speaker in the poem is giving advice on how to beg. The poem begins:

If you got hiv, say aids. If you a girl,

say you’re pregnant–nobody gonna lower

themselves to listen for the kick.

The speaker exhibits a fairly sophisticated understanding of how the sensibilities of potential givers can be manipulated:

If you’re crippled don’t

flaunt it. Let ‘em think they’re good enough

Christians to notice.

The outlook of the speaker can reasonably be described as cynical, both regarding acceptable strategies to use when begging, and regarding the motives of the people targeted, who are taken to be moved not so much by compassion as by a desire to uphold a certain self-image. The poem concludes:

Don’t say you pray,

say you sin. It’s about who they believe

they is. You hardly even there.

The poem provoked fierce criticism on social media. People objected to Carlson-Wee using black vernacular speech patterns, to his making the speaker black, and to his inclusion of the word “crippled,” which some viewed as “ableist. The criticism prompted the editors at The Nation to issue an apology in which they wrote:

We are sorry for the pain we have caused to many communities affected by this poem….When we read the poem we took it as a profane, over-the-top attack on the ways in which members of many groups are asked, or required, to perform the work of marginalization. We can no longer read it that way.

Anders Carlson-Wee also offered an apology on Twitter, writing:

I am sorry for the pain I have caused, and I take responsibility for that. I intended the poem to address the invisibility of homelessness, and clearly it doesn’t work. Treading anywhere close to blackface is horrifying to me and I am profoundly regretful.

One of the downsides to social media is that controversies can easily reduce to a few verbal missiles–brief assertions, sharp put-downs, expressions of incredulity or outrage–tossed back and forth. For example, essayist Roxanne Gay, condemning Carlson-Wee (who is white) for using black vernacular locutions, offered all writers this advice: “Know your lane.” Katha Pollitt, who writes regularly for the nation, opined that the magazine’s apology “looks like a letter from a re-education camp.” What is needed, though, is a more careful reflection on the theoretical issues involved. Read more »

by Dwight Furrow

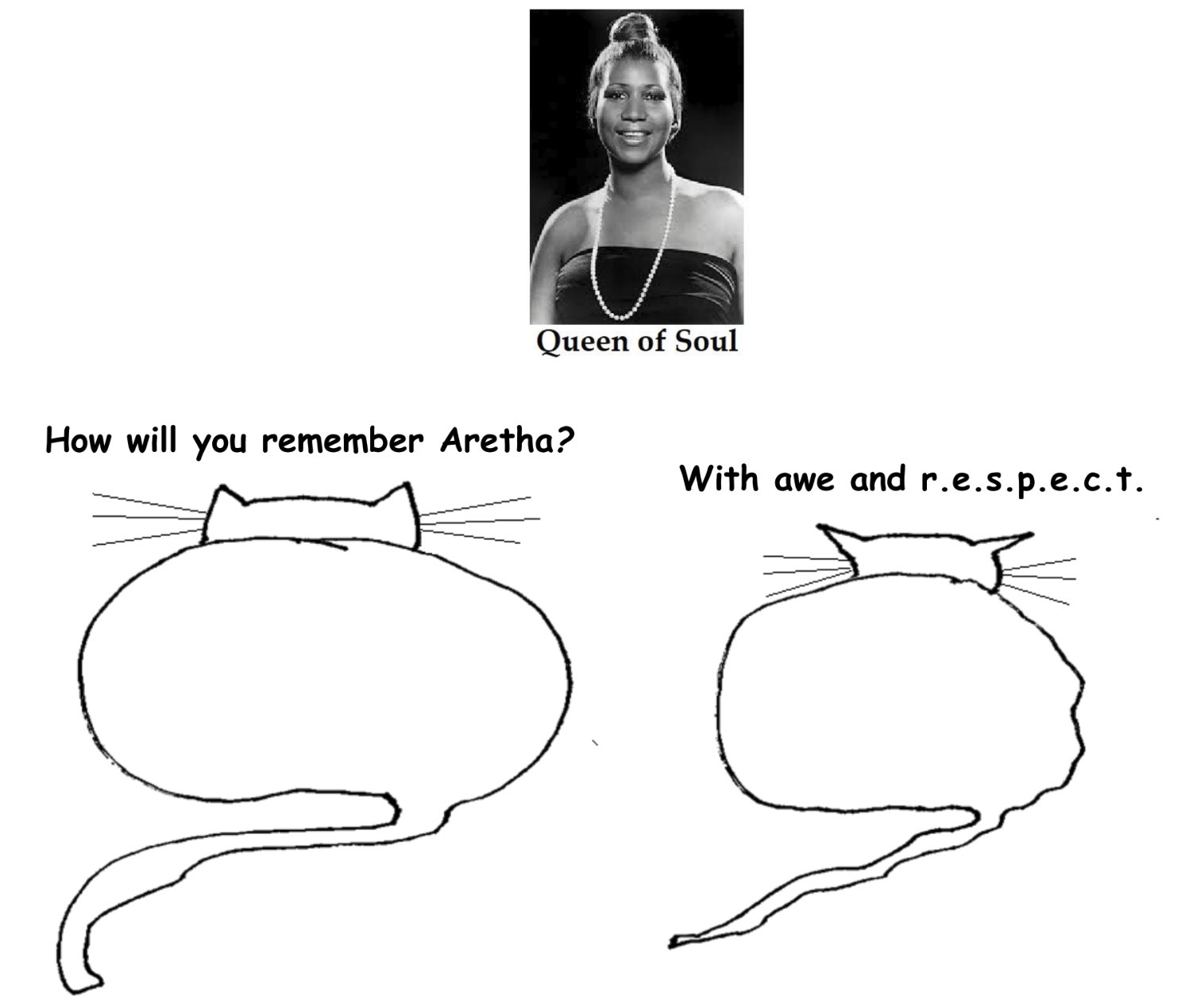

That music and emotion are somehow linked is one of the more widely accepted assumptions shared by philosophical aesthetics as well as the general public. It is also one of the most persistent problems in aesthetics to show how music and emotion are related. Where precisely are these emotions that are allegedly an intrinsic part of the musical experience? Three general answers to this question are possible. Either the emotion is in the musician—the composer or performer—in which case the music is expressing that emotion. Or the emotion is in the music itself, in which case the music somehow embodies the emotion. Or the emotion is in the listener, in which case the music arouses the emotion.

That music and emotion are somehow linked is one of the more widely accepted assumptions shared by philosophical aesthetics as well as the general public. It is also one of the most persistent problems in aesthetics to show how music and emotion are related. Where precisely are these emotions that are allegedly an intrinsic part of the musical experience? Three general answers to this question are possible. Either the emotion is in the musician—the composer or performer—in which case the music is expressing that emotion. Or the emotion is in the music itself, in which case the music somehow embodies the emotion. Or the emotion is in the listener, in which case the music arouses the emotion.

I suspect the most popular view among the public, since it draws on the romantic views of the self and creativity which is still very much with us, is that music expresses the emotional state of the artist. But this is implausible. I doubt that song writers when writing a sad song are in a state of sadness. At best the song could be expressing a composer’s understanding of sadness or perhaps a memory of a previous emotional state. But even if that were granted, we usually know little about the emotional states of composers, song writers, or musicians and so the listener is forced to somehow “read off” the emotion from the music itself. The emotional state of the artist just seems irrelevant to the process of determining the emotive content of the music. No doubt some composers and musicians are expressing their emotions in specific cases. But the only way to know that, short of inferring it from biographical details, is to infer it from the music itself, which seems to locate the emotion in the music. Read more »

by Carl Pierer

Socialism is in crisis. Until a few years ago, this mantra kept being repeated and a terminally ill  sickness was constantly diagnosed for the once powerful idea. And still, after the impressive Sanders campaign of 2016, the electoral success of Jeremy Corbyn in the 2017 general election, as well as the – for many – surprising victory of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in the democratic primary in New York, writers continue to assure us that the idea is, if not dead, having serious problems. In any case, the idea of socialism seemed until recently a relic of the industrial past with little to say about contemporary society.

sickness was constantly diagnosed for the once powerful idea. And still, after the impressive Sanders campaign of 2016, the electoral success of Jeremy Corbyn in the 2017 general election, as well as the – for many – surprising victory of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in the democratic primary in New York, writers continue to assure us that the idea is, if not dead, having serious problems. In any case, the idea of socialism seemed until recently a relic of the industrial past with little to say about contemporary society.

In his brief book “The Idea of Socialism: Towards a Renewal”, which first appeared in its German version in 2015 and then again in 2017, appended with 2 talks given during award ceremonies, Axel Honneth attempts to update socialist ideas for the 21st century. Honneth observes that what once was an idea to inspire enormous popular movements and demanded to be taken seriously even by its most ardent detractors, has lost almost all of its force. The formulation of socialist utopias, if it has not ceased to exist entirely, has become rarer and their attraction diminished. To cite Jameson: “(…) it is easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism”[i]. Honneth, a current descendent of the Frankfurt School and drawing inspiration from Hegel, Dewey, and Habermas, thus raises the question of why the idea of socialism has lost its ability to unveil the reification of the status quo. Read more »

by Gerald Dworkin

We (the readers of 3QD; I know there are many people who disagree) can take it as given that Alex Jones is a thoroughly evil person. Someone who spreads false statements that the parents of the children killed in the Sandy Hook shooting staged the whole thing deserves lots of bad things happening to him, e.g. lose all the money he has made from the web in a defamation suit that the parents have filed, have people boycott his dietary supplement hoax.

We (the readers of 3QD; I know there are many people who disagree) can take it as given that Alex Jones is a thoroughly evil person. Someone who spreads false statements that the parents of the children killed in the Sandy Hook shooting staged the whole thing deserves lots of bad things happening to him, e.g. lose all the money he has made from the web in a defamation suit that the parents have filed, have people boycott his dietary supplement hoax.

The question I want to discuss here is whether he should not be allowed to use the various social-media platforms, e.g. Facebook, YouTube, Apple, Spotify, which have recently denied him access. I begin with five problematic arguments for censoring Jones. I then consider some possibly better ones.

1. Facebook removal does not violate the first amendment

The premise is correct . There can be no violation of that amendment by Facebook since the amendment states clearly that “Congress shall make no law…abridging the freedom of speech…” Courts have interpreted this to mean that the Federal Government shall not so so. Further they have interpreted the Due Process clause of the Fourteenth amendment to extend this impermissibility to state governments. This is why the University of California is bound by the First Amendment and Harvard is not.

But the mere fact that banning Jones is consistent with the First Amendment merely shows such a ban is not unconstitutional. It does not advance any positive reason for censorship. It only shows that one argument against censorship fails. Read more »

by Robert Fay

The great Mexican writer Sergio Pitol died in April. He was 85, a recipient of the Cervantes Award—the highest honor for works in the Spanish language—and in his The Art of Flight trilogy, he writes of his 20 years living and working in Europe, “the thread that ties those years together, I’ve always known, is literature…for many years, my experience traveling, reading, writing merged into a single experience.” The particular life he lead as “a man of letters,” is now unrepeatable, even by today’s best writers. And it’s not a lack of talent or courageousness, but of the inevitable consequence of cultural indifference. Literature must be respected or at least feared to have relevance, and the resulting electricity from this attention is the crucial spark for great lives, competitive coteries, great books, and perhaps most critical of all, a savvy reading public who awaits genius, demands it, and who lives for the spirit of the logos.

The Art of Flight, written in Pitol’s final years, demonstrates a freedom of form that many writes yearn to explore, but find they have neither the courage nor the savoire faire to take on. The trilogy is a pastiche of memoir, travel reportage, literary criticism, dream diaries and stolen glances from Pitol’s working notebooks. In 1960 after scattered work as a translator, Pitol joined the Mexican Foreign Service as a cultural attaché and served for over 20 years at a number of posts, including Moscow, Barcelona, Belgrade and Rome. His career afforded him the privilege to meet an enviable array of international writers, artists, academics and diplomats, an opportunity well beyond what Mexico City and its regional, Spanish-language literary milieu could have provided. Read more »

by Akim Reinhardt

“In Memory of Franz Klammer”

Franz Klammer soared

down alpine mounts,

His glory assured

by the clock’s count

The lord of Austria,

the king of the hill,

the master of the Alps,

the bringer of thrills

His grace, his speed,

defied laws of nature

His beautiful name

redefined nomenclature

Franz Klammer! Franz Klammer!

you were the best,

sparkling Olympic gold

draped ‘cross your chest.

We shall always remember

how you stormed down the mountains,

and now that you’re gone

we shall always be counting

The hours since you left,

and awaiting the day

when a soothsayer comes

and we all hear him say:

“Look up on the hill,

yonder snowy peak

A young man races hither

Come see him streak

Down the mountain side

like a B-29 bomber

Roaring like thunder,

he looks like dear Klammer!

With the wind in his face,

the mountain in his hands,

such bold, Teutonic grace,

he looks like beloved Franz!”

But alas, I do fear

such a day will not come

during my life

He was the only one

One of a kind

as down the mountains he tread–

What’s that you say?

Franz Klammer’s not dead?

But that must be a mistake,

we visited him just last week

He was rotting at the hospice,

I heard the doctor speak

About the ugly brain tumor

the gangrene and gonorrhea,

the lupus, the scurvy,

the heartburn, the diarrhea

They said he was a gonner

just a matter of time–

What? They let him out ?

He’s going home? He feels fine?!

This is ludicrous! I thought–

No, no! I’m not bitter

But between you and me,

Jean-Claude Killy was better. Read more »

by Anitra Pavlico

In April, the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee voted favorably on a bill aimed at protecting Special Counsel Robert Mueller from being fired by the President without good cause. Some Republican senators doubted the legality of the bill, based on a one-judge dissent in a U.S. Supreme Court case decided in 1988, Morrison v. Olson. One senator even considered himself “bound” by Justice Scalia’s dissent in that case. A dissent in a case in Supreme Court, or any court, is the losing argument and cannot bind anyone to follow its reasoning. Was Scalia’s opinion correct and the rest of the Supreme Court justices made a terrible mistake? Maybe shooting down the bill is what the framers of the Constitution–because this is in fact a constitutional question–would have wanted? Well, no. As constitutional scholar Victoria Nourse writes, “Cloaking themselves in Scalia’s lonely and incorrect dissenting opining, senators opposing the Integrity Act are attempting to upend the Constitution by embracing a dangerous constitutional argument contrived to render the President immune from scrutiny.”

The so-called unitary executive theory animates critics’ claims that the bill impermissibly curtails the President’s authority. Under this theory, any attempt to limit the President’s control over the executive branch is seen as unconstitutional. You may recall it rearing its head during George W. Bush’s presidency, as its adherents relied on it to justify the infamous “torture memo” drafted by White House counsel John Yoo, who argued, “The historical record demonstrates that the power to initiate military hostilities, particularly in response to the threat of an armed attack, rests exclusively with the President. [. . .] Congress’s support for the President’s power suggests no limits on the Executive’s judgment whether to use military force in response to the national emergency.” Carried to its extreme, the unitary executive theory could potentially undermine a democracy. Read more »

by Andrea Scrima

Try it: try talking about the subject of reading without drifting off into how the Internet has changed the way we absorb information. I, along with the majority of people I know whose reading habits were formed long before the advent of digital magazines and newspapers, Google Books, blogs, RSS feeds, social media, and Kindle, usually feel I’m only really reading when it’s printed matter, under a reading lamp, with the screen and phone turned off. But the reality is that I do a vast amount of reading online.

Try it: try talking about the subject of reading without drifting off into how the Internet has changed the way we absorb information. I, along with the majority of people I know whose reading habits were formed long before the advent of digital magazines and newspapers, Google Books, blogs, RSS feeds, social media, and Kindle, usually feel I’m only really reading when it’s printed matter, under a reading lamp, with the screen and phone turned off. But the reality is that I do a vast amount of reading online.

Unsurprisingly, my attention span has gotten jumpy: I click from one article to another, suddenly remember a mail I need to write, consult the online dictionary on a browser that has at least thirty-five open tabs, and before I reach my destination, I see that I have several new Facebook notifications and check these first. By the time I click on the dictionary, a half hour has been lost and I can no longer remember the word I intended to look up. The result of all this is the humbling admission to a new handicap: the need for an Internet access-blocker with a Black List.

For my seventeen-year-old son and his growing brain, the potential for relentless distraction is far more pernicious. This is a kid who was read to every night of the first thirteen years of his life for at least an hour at bedtime, more often than not longer, and yet the dominance of smart-phone technology in his young life means that the greater part of his access to the world of ideas now takes place online.

I’m not going to explore the anxiety of parenthood in the digital age or argue the pros and cons of the Internet here; I myself am far too entrenched to ponder a life without it. But what strikes me is the profound change we’ve undergone in our collective ability to think critically. In an era of fake news and AI technology sophisticated enough to produce video footage that looks like the real thing, the conclusion I’ve come to is this: the ability to read is not the only thing we have to salvage for the next generation; we have to save, from oblivion, our ability to read between the lines. Read more »

by Bill Murray

Polynesia could swallow up the entire north Atlantic Ocean. It’s that big.

Polynesia could swallow up the entire north Atlantic Ocean. It’s that big.

Only half of one per cent of Polynesia is land, and 92 per cent of that is New Zealand. Then there’s Tonga and Samoa, the Cook and Hawaiian islands, the French possessions, and back in its own lonely corner, Rapa Nui, the famous Easter Island. Four and a half hours flying time to South America and six hours to Tahiti, Rapa Nui is a mote, a tiny place that feels tiny, forlorn, a footnote.

How in the world did proto-Polynesians cast their civilization from Papua New Guinea all the way to Rapa Nui in canoes, with thousand year old tech, sailing against prevailing winds and all odds?

If you think about it at all, you might suppose Rapa Nui was an accidental discovery, storm-damaged canoes drifting off course, perhaps, or voyages of exile dashed upon obscure rocks. Who imagines resolute, purposeful voyages of discovery on stone-age ships no match for the vastness of the sea?

I do. I fancy single-minded voyages of exploration carried out by well-provisioned scouts sailing with, say, a month’s food, who set out in the more difficult direction, “close to the wind.” If no land were found in a fortnight, when half the food was gone, they could sail home downwind, faster. Read more »

by Richard Passov

Researching the history of a particular computer has taken me along an arc  spanning George Boole to Claude Shannon. By some measures the works of these men combine to give us our modern, programmable computer.

spanning George Boole to Claude Shannon. By some measures the works of these men combine to give us our modern, programmable computer.

Shannon recast Boole’s Calculus of Thought into the modern symbolism for computer logic. And while that work has been labeled as the most important master’s thesis of the 20th century, ten years later Shannon would release a more profound work – his Theory of Information.

Profound works are sometimes simple and perhaps this is why a few mathematicians derided Information Theory. Shannon, secure in his finding, generally ignored his critics. Among his many endeavors and though unnecessary, John Pierce took up Shannon’s defense. That’s how I found his writings.

Sometimes men have been concerned with religion, sometimes with mathematics and philosophy, sometimes with exploration, trade and conquest, sometimes with the theory and practice of government, sometimes with ancient learning, sometimes with the arts. —John R. Pierce in Electrons, Waves and Messages

* * * * * * * * * *

Pierce and Shannon worked together at Bell Labs. By the time Shannon came aboard Pierce was a mainstay, having risen to director of “…all research concerned with Electrical Communications.” Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Michael Liss

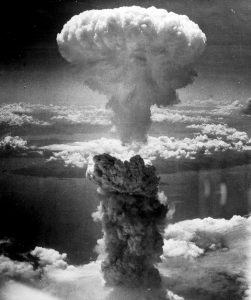

Will you know what to do when the atomic bomb drops? This question, and others like it, are vividly on display in the 4K restoration of Jayne Loader, Kevin Rafferty, and Pierce Rafferty’s 1982 documentary, The Atomic Café. Having seen the movie when it was first released (my kids’ reaction to this information was “of course you did”) I was determined to return to my roots. But, this being 2018, I took full advantage of technologies not available in the Neolithic Age: I quickly went online and bought two tickets for a night when the filmmakers themselves would be there for a Q&A. Then I fired off a few text messages to friendly liberals of a similar vintage to see who else was going, because you really don’t go to one of these things without a posse.

Will you know what to do when the atomic bomb drops? This question, and others like it, are vividly on display in the 4K restoration of Jayne Loader, Kevin Rafferty, and Pierce Rafferty’s 1982 documentary, The Atomic Café. Having seen the movie when it was first released (my kids’ reaction to this information was “of course you did”) I was determined to return to my roots. But, this being 2018, I took full advantage of technologies not available in the Neolithic Age: I quickly went online and bought two tickets for a night when the filmmakers themselves would be there for a Q&A. Then I fired off a few text messages to friendly liberals of a similar vintage to see who else was going, because you really don’t go to one of these things without a posse.

I was not to be disappointed. Six of us converged on the newly renovated, but still decidedly funky Film Forum. First, my 26-year old son, who spared me the dubious honor of being the only person in the audience in a suit, white shirt, and dark tie (we looked like refugees from a Book of Mormon casting call). Then four of the like-minded, three of whom could be described as gracefully aging hipsters (wearing, respectively, a pair of gray braids, a great-looking gray Van Dyke, and a graying inside out T-shirt) and finally, my pal (and liberal conscience) Melinda.

I could write books about Melinda, and I should, because there aren’t enough Melindas in the world. She’s a Yellow Dog Texas Democrat who brought with her to New York an indestructible accent, an odd affinity for driving minivans as basic transportation in a car-unfriendly city, and an inexhaustible capacity for good works. If there was a protest anywhere, Melinda knew about it, probably organized it, and occasionally got arrested for it. There are still places that are off-limits to her, for a variety of Deep State-ish reasons. Greenwich Village, of course, is not one of them. Melinda is the genuine article.

But I digress. The movie is the thing you came to see, and the movie is what you should get. Read more »

I didn’t even know he had written a book set in New York City in the wake of catastrophic climate change. By “he” I mean Kim Stanley Robinson. But there it was on the table, New York 2140. A couple quick glances told me that, yes, it was set after the sea rise. That’s something very real to me. I’d lived through Hurricane Sandy’s flooding on the Jersey shore – I was living in Jersey City at the time. I was without power for four or five days (I forget which), but others were without power for two or more weeks–not to mention flooding and homes destroyed, and the effects ripple out from there. They’re still rippling.

I didn’t even know he had written a book set in New York City in the wake of catastrophic climate change. By “he” I mean Kim Stanley Robinson. But there it was on the table, New York 2140. A couple quick glances told me that, yes, it was set after the sea rise. That’s something very real to me. I’d lived through Hurricane Sandy’s flooding on the Jersey shore – I was living in Jersey City at the time. I was without power for four or five days (I forget which), but others were without power for two or more weeks–not to mention flooding and homes destroyed, and the effects ripple out from there. They’re still rippling.

When climate change hits home – we can’t stop it, it’s already started, and the sea will rise appreciably no matter what we do – will we survive? Well of course we will, “we” meaning humans, some of us. But how will we live? Our spirit, what of that?

Perhaps Robinson offers some insight. Not, mind you, that I somehow think KSR is a prophet. He isn’t (a prophet) and he doesn’t (know the future). But he’s a smart guy with a good imagination and really, that’s the best we can do under the circumstances, no?

And so I began to read the New York 2140.

Caveat: This is not a review, it’s a consideration, a meditation? It’s full of spoilers. I’ve been re-reading the book and coming to grips with it. Or something. An earlier and somewhat different piece on the book.

Not about the future, but the present

As I was reading my mind collided with that old cliché:

Science fiction’s not about the future, it’s about the present.

But then isn’t all fiction like that? No matter when and where it’s set, it is necessarily about the authorial present, because that’s what the author lives, day in and day out. The rest is costumes, stage sets, blocking, and action.

That’s what I was thinking. But I was also thinking that THAT’s not why I’m reading New York 2140, not at all. It’s about NYC after the climate apocalypse, and that’s why it interests me. It’s as though I was almost looking for a how-to-do-it book. I say “almost” because when you put it that baldly it seems silly and I wasn’t really thinking that. But sorta, kinda’, almost. Read more »

by Nickolas Calabrese

There are two dogmatic justifications (or really non-justifications) that are provided time and time again when discussing the production of abstract art. First is ‘material exploration’, and second is ‘freedom’. If you have ever contemplated certain abstract artworks with skepticism, rest assured that your incredulity is not crazy. Even if the work has been accepted and defended by respectable critics, there is a profoundly problematic reasoning employed in the defense of a good portion of what I will call for present purposes dogmatic abstraction. This text will address what counts as weak justification for abstract art, as well as why justification in art is essential for understanding it at all. Justifying artworks is equivalent to having an alibi – it is the only good reason why the artist isn’t lying. It is the basis from which we can discern good from bad art.

The problem with speaking about art dogmatically is that it becomes an assumption, something taken for granted as true without proper interrogation. When reasons are supposedly beyond critique, then the artwork in question is bulletproofed. Providing and obtaining reasons in the artworld is something that is almost holy – it is a leap of faith because art usually has no precedent save for other artworks. Formally an artwork requires reasons because it did not exist hitherto and has no use until the maker wills it. Accordingly, the consecrated act of providing and receiving reasons – of justification – is what is at stake when dogma is offered instead of a shrewdly thoughtful account. These two dogmatic suppositions are not just false in general but false in detail. Read more »