by Michael Klenk

Someone else gets more quality time with your spouse, your kids, and your friends than you do. Like most people, you probably enjoy just about an hour, while your new rivals are taking a whopping 2 hours and 15 minutes each day. But save your jealousy. Your rivals are tremendously charming, and you have probably fallen for them as well.

Someone else gets more quality time with your spouse, your kids, and your friends than you do. Like most people, you probably enjoy just about an hour, while your new rivals are taking a whopping 2 hours and 15 minutes each day. But save your jealousy. Your rivals are tremendously charming, and you have probably fallen for them as well.

I am talking about intelligent software agents, a fancy name for something everyone is familiar with: the algorithms that curate your Facebook newsfeed, that recommend the next Netflix film to watch, and that complete your search query on Google or Bing.

Your relationships aren’t any of my business. But I want to warn you. I am concerned that you, together with the other approximately 3 billion social media users, are being manipulated by intelligent software agents online.

Here’s how. The intelligent software agents that you interact with online are ‘intelligent agents’ in the sense that they try to predict your behaviour taking into account what you did in your online past (e.g. what kind of movies you usually watch), and then they structure your options for online behaviour. For example, they offer you a selection of movies to watch next.

However, they do not care much for your reasons for action. How could they? They analyse and learn from your past behaviour, and mere behaviour does not reveal reasons. So, they likely do not understand what your reasons are and, consequently, cannot care for it.

Instead, they are concerned with maximising engagement, a specific type of behaviour. Intelligent software agents want you to keep interacting with them: To watch another movie, to read another news-item, to check another status update. The increase in the time we spend online, especially on social media, suggests that they are getting quite good at this. Read more »

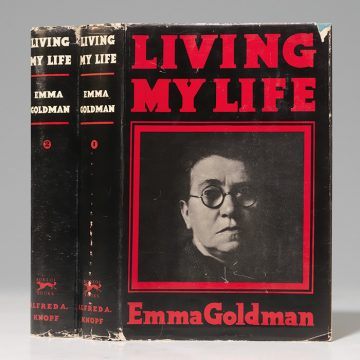

In a political era where many of the ‘isms’ in radical politics: Marxism, socialism, communism, anarchism, Trotskyism have either been discredited or have lost their appeal and force in western democracies, I found it refreshing to visit the life of one individual deeply involved in shaping those radical movements in the twentieth century: the anarchist, Emma Goldman, in her autobiography Living My Life.

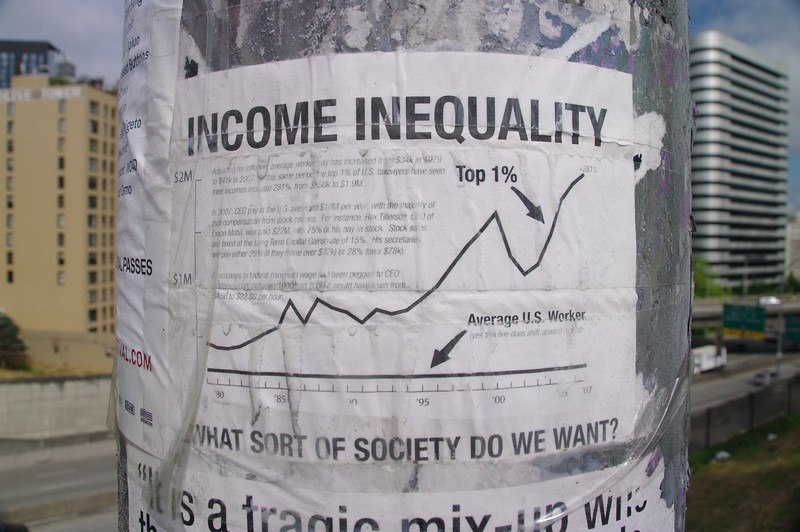

In a political era where many of the ‘isms’ in radical politics: Marxism, socialism, communism, anarchism, Trotskyism have either been discredited or have lost their appeal and force in western democracies, I found it refreshing to visit the life of one individual deeply involved in shaping those radical movements in the twentieth century: the anarchist, Emma Goldman, in her autobiography Living My Life. There is widespread concern about increasing or high economic inequality in many countries, both rich and poor. At a global level, according to the World Inequality Report 2018, the richest 1% in the world reaped 27% of the growth in world income between 1980 and 2016, while bottom 50% of the population got only 12%. Over roughly the same period, however, absolute poverty by standard measures has generally been on the decline in most countries. By the widely-used World Bank estimates, in 2015 only about 10 per cent of the world population lived below its common, admittedly rather austere, poverty line of $1.90 per capita per day (at 2011 purchasing power parity), compared to 36 per cent in 1990. This decline is by and large valid even if one uses broader measures of poverty that take into account some non-income indicators (like deprivations in health and education) for the countries for which such data are available.

There is widespread concern about increasing or high economic inequality in many countries, both rich and poor. At a global level, according to the World Inequality Report 2018, the richest 1% in the world reaped 27% of the growth in world income between 1980 and 2016, while bottom 50% of the population got only 12%. Over roughly the same period, however, absolute poverty by standard measures has generally been on the decline in most countries. By the widely-used World Bank estimates, in 2015 only about 10 per cent of the world population lived below its common, admittedly rather austere, poverty line of $1.90 per capita per day (at 2011 purchasing power parity), compared to 36 per cent in 1990. This decline is by and large valid even if one uses broader measures of poverty that take into account some non-income indicators (like deprivations in health and education) for the countries for which such data are available.

For me, a highlight of an otherwise ill-spent youth was reading mathematician John Casti’s fantastic book “

For me, a highlight of an otherwise ill-spent youth was reading mathematician John Casti’s fantastic book “ Have you ever been in this situation where you had to get a group of 3 men and their sisters across a river, but the boat only held two and you had to take precautions to ensure the women got across without being assaulted?

Have you ever been in this situation where you had to get a group of 3 men and their sisters across a river, but the boat only held two and you had to take precautions to ensure the women got across without being assaulted?