by Anitra Pavlico

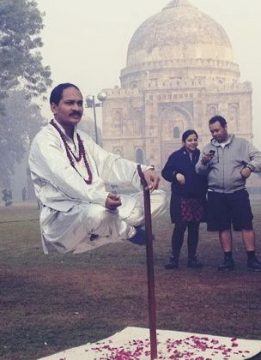

It is difficult nowadays not to be mindful of how ubiquitous the mindfulness movement has become. A Fortune article from 2016 described meditation as a “billion-dollar business”: “From Bridgewater’s Ray Dalio and Salesforce’s Marc Benioff to Goldman Sachs traders and Google programmers, Big Business loves meditation.” This is perhaps reason enough to stay away from it, or at least to stay away from anything that charges you money to do something that you can easily do for free–namely, sit and do nothing. But a surprising number of observers have pointed to other shortcomings or even dangers in meditation and mindfulness practices.

There have been so many articles on the incredible benefits of meditation (which I’ll use interchangeably with mindfulness) that you come to feel you’re putting yourself in harm’s way by not doing it. As Masoumeh Sara Rahmini wrote recently in The Conversation, however, citing a study published in Perspectives on Psychological Science, “scientific data on mindfulness is limited . . . Studies on mindfulness are known for their numerous methodological and conceptual problems.” She notes that the journal PLOS ONE retracted a meta-analysis of mindfulness, citing concerns over methodology as well as undeclared financial conflicts of interest. Rahmini also takes issue with the Westernized version of Buddhism that is sold to modern mindfulness practitioners–one that is divorced from centuries of Buddhist tradition. She credits, or blames, Jon Kabat-Zinn, among others. Kabat-Zinn, the founder of the popular Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program offering mindfulness training to help with stress and pain, has argued that the MBSR technique contains the “essence” of Buddhism, which he says is universal and supported by science.

The trouble is that what used to be a spiritual practice, supported by a framework of teachings and in an organized setting, with spiritual guides, is now a definition-less practice, unmoored from tradition, lacking a scaffolding in case you should trip, devoid of a philosophy. Read more »

Unfortunately, you have a brain tumor. You don’t know it yet. Your doctor doesn’t know it yet. But you are beginning to have symptoms. The tumor is pressing on surrounding brain tissue and causing you develop a number of delusional beliefs. You believe you are the best swimmer in the world. You believe that dogs and cats are aliens. You believe that you invented the apostrophe. You also, as it happens, believe that you have a brain tumor.

Unfortunately, you have a brain tumor. You don’t know it yet. Your doctor doesn’t know it yet. But you are beginning to have symptoms. The tumor is pressing on surrounding brain tissue and causing you develop a number of delusional beliefs. You believe you are the best swimmer in the world. You believe that dogs and cats are aliens. You believe that you invented the apostrophe. You also, as it happens, believe that you have a brain tumor. “Taxi to Bethlehem, taxi to Jericho!” the man at a tourism kiosk is shouting, as I make my way from the tram to Jaffa Gate, known also as Hebron Gate, to Muslims as “Bab al Khalil,” or “door of the friend,” named after Hebron where the prophet Ibrahim/Abraham (Khalil al Allah “God’s Friend”) is laid to rest. Of significance too, is the association of this gate with King David’s (prophet Dawud’s) chamber, for followers of the three Abrahamic faiths: the crusaders named it “King David’s Gate.” It is one of the seven main stone portals of the walled city of Jerusalem.

“Taxi to Bethlehem, taxi to Jericho!” the man at a tourism kiosk is shouting, as I make my way from the tram to Jaffa Gate, known also as Hebron Gate, to Muslims as “Bab al Khalil,” or “door of the friend,” named after Hebron where the prophet Ibrahim/Abraham (Khalil al Allah “God’s Friend”) is laid to rest. Of significance too, is the association of this gate with King David’s (prophet Dawud’s) chamber, for followers of the three Abrahamic faiths: the crusaders named it “King David’s Gate.” It is one of the seven main stone portals of the walled city of Jerusalem.

Calls for a Manhattan Project–style crash effort to develop artificial intelligence (AI) technology are thick on the ground these days. Oren Etzioni, the CEO of the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence, recently issued such a call on

Calls for a Manhattan Project–style crash effort to develop artificial intelligence (AI) technology are thick on the ground these days. Oren Etzioni, the CEO of the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence, recently issued such a call on

Fans are the people who know the quotes, the dates of publication, the batting averages, the bassist on this album, the team that general manager coached before. I am not a fan. Don’t get me wrong. I’m full of enthusiasms. But I can’t match you statistic for statistic. I haven’t read the major author’s minor novel. I don’t care who the bassist was. You win. I’m an amateur.

Fans are the people who know the quotes, the dates of publication, the batting averages, the bassist on this album, the team that general manager coached before. I am not a fan. Don’t get me wrong. I’m full of enthusiasms. But I can’t match you statistic for statistic. I haven’t read the major author’s minor novel. I don’t care who the bassist was. You win. I’m an amateur. When I watched the 2019 documentary on Apollo 11, it carried me back not to the summer of 1969, when it happened, but to the mid-1980s, when I was an undergrad. I was eight when Apollo 11 launched; of course I was aware of the space program and the moon landings, but I don’t have any memories of everyone gathering around to watch those first steps on another world. My parents weren’t particularly interested, and I don’t remember being caught by the spirit of the times myself.

When I watched the 2019 documentary on Apollo 11, it carried me back not to the summer of 1969, when it happened, but to the mid-1980s, when I was an undergrad. I was eight when Apollo 11 launched; of course I was aware of the space program and the moon landings, but I don’t have any memories of everyone gathering around to watch those first steps on another world. My parents weren’t particularly interested, and I don’t remember being caught by the spirit of the times myself. cinematic representations of Muslims. Stage One features stereotyped figures (the taxi driver, terrorist, cornershop owner, or oppressed woman). Stage Two involves a portrayal that subverts and challenges those stereotypes. Finally, Stage Three is ‘the Promised Land, where you play a character whose story is not intrinsically linked to his race’. Does

cinematic representations of Muslims. Stage One features stereotyped figures (the taxi driver, terrorist, cornershop owner, or oppressed woman). Stage Two involves a portrayal that subverts and challenges those stereotypes. Finally, Stage Three is ‘the Promised Land, where you play a character whose story is not intrinsically linked to his race’. Does

Our expectations sculpt neural activity, causing our brains to represent the outcomes of our actions as we expect them to unfold. This is consistent with a growing psychological literature suggesting that our experience of our actions is biased towards what we expect. —

Our expectations sculpt neural activity, causing our brains to represent the outcomes of our actions as we expect them to unfold. This is consistent with a growing psychological literature suggesting that our experience of our actions is biased towards what we expect. — Into the Woods

Into the Woods

My friend does not use punctuation when he texts, so there is a stream-of-consciousness quality to much of his communications. According to the fine folks at

My friend does not use punctuation when he texts, so there is a stream-of-consciousness quality to much of his communications. According to the fine folks at

The right to own guns is typically justified by the fundamental right to self-defense against bad guys, either our fellow citizens or the state itself if it were to turn tyrannical. Both of these have a superficial appeal but fail in obvious ways. Guns are an effective means of defending oneself against bad guys only so long as they don’t have guns too (because being equally armed doesn’t add up a defense against those who can pick and choose their moment of aggression). Civilians with guns are also ineffective against the armies and ruthless terroristic violence of a truly tyrannical regime.

The right to own guns is typically justified by the fundamental right to self-defense against bad guys, either our fellow citizens or the state itself if it were to turn tyrannical. Both of these have a superficial appeal but fail in obvious ways. Guns are an effective means of defending oneself against bad guys only so long as they don’t have guns too (because being equally armed doesn’t add up a defense against those who can pick and choose their moment of aggression). Civilians with guns are also ineffective against the armies and ruthless terroristic violence of a truly tyrannical regime.