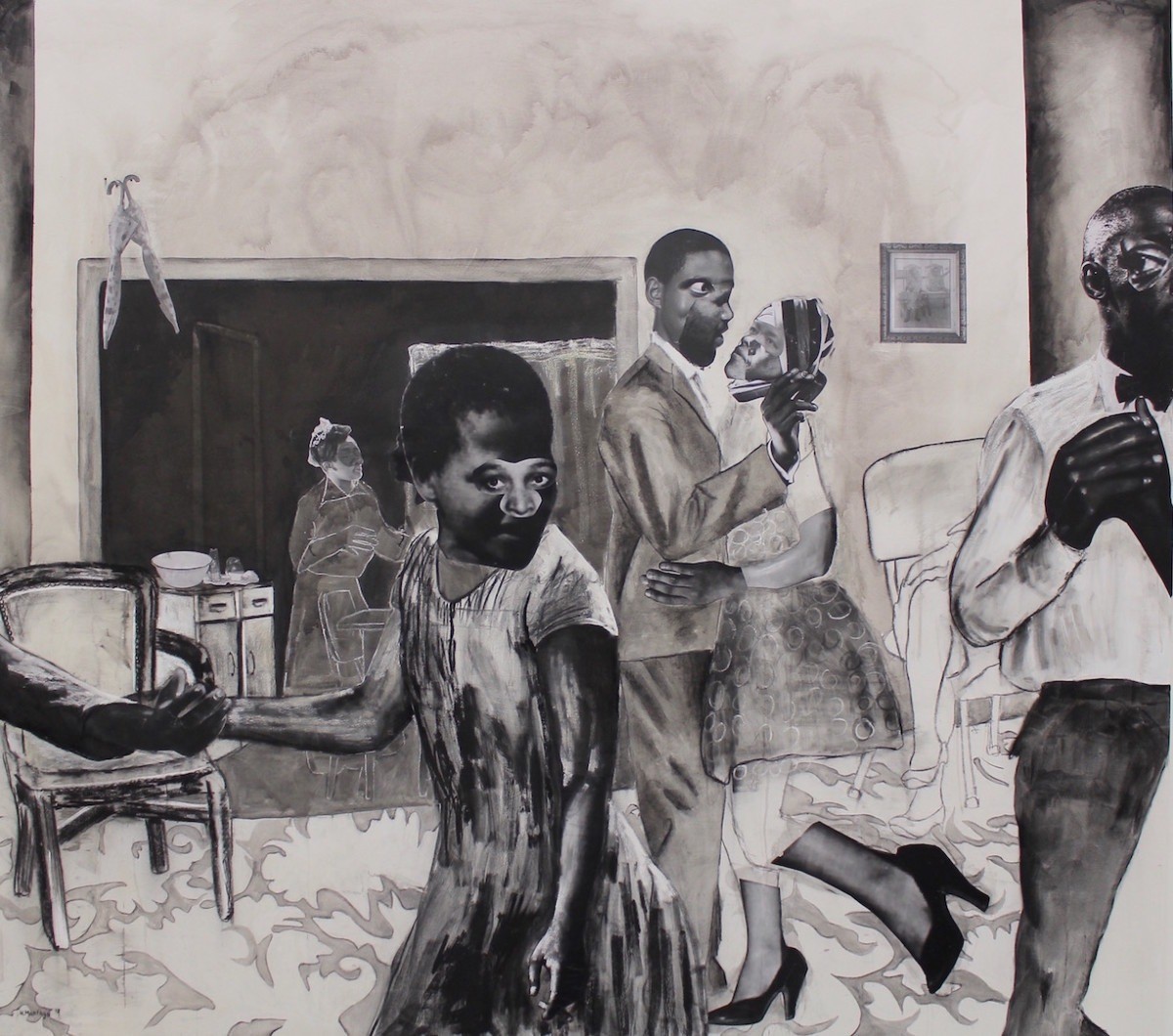

by Tamuira Reid

The apartment in West Harlem, five buildings down on the left. The apartment just past the pawn shop, across from the Rite-Aid, parallel to the barber’s where all the pretty boys hangout waiting to get a Friday night shave. The apartment past the deli were you get cheese and pickle sandwiches and the all-night liquor store and the ATM machine no one is dumb enough to use.

The apartment in West Harlem, five buildings down on the left. The apartment just past the pawn shop, across from the Rite-Aid, parallel to the barber’s where all the pretty boys hangout waiting to get a Friday night shave. The apartment past the deli were you get cheese and pickle sandwiches and the all-night liquor store and the ATM machine no one is dumb enough to use.

The apartment at the top of the stairs with the impossibly high ceilings and the blue bathroom door, the door you labor behind for twelve hours before going to the hospital, your body threatening to push another body out. The apartment where you bring him home, his pink baby body covered in muslin and sweat. The apartment with the wide cracked stoop where you rest with his father just long enough to catch your breath, to say holy shit, he’s beautiful.

The apartment you now stand in front of, seven years later, holding onto a box of birthday-wrapped legos and your son’s hand. The apartment at Broadway and 138th. The apartment on the way to the party. The apartment half-way down a steep hill, the hill you lug your grocery bags down, and the hill you climb with your luggage. The apartment with a broken oven but perfect sunlight and enough closets to hide things in. The apartment in an old brownstone next to other old brownstones, framed by planter boxes filled with tulips and beer cans and night club fliers. The apartment owned by an angry old man and his needy young wife, a man who is stretched so thin he could give two fucks when you tell him the heat is out. The apartment where you sleep in a pile for warmth, arms and legs wrapped around one another, the baby squished between across the two of you. Read more »

I don’t know a lot about guns.

I don’t know a lot about guns.

Smacked my head on the pavement while jogging across campus in the rain. Had my hands on my stomach, holding documents in place underneath my shirt to keep them dry. So when my foot went out after skipping over a puddle, I couldn’t get my front paws down in time to brace my fall as I corkscrewed through the air, landing on my hip and shoulder, and whiplashing my head downward. Consequently I don’t have the brain power to crank out 2,000 fresh words. So here’s a dated piece about Baby Boomer navel gazing and ressentiment.

Smacked my head on the pavement while jogging across campus in the rain. Had my hands on my stomach, holding documents in place underneath my shirt to keep them dry. So when my foot went out after skipping over a puddle, I couldn’t get my front paws down in time to brace my fall as I corkscrewed through the air, landing on my hip and shoulder, and whiplashing my head downward. Consequently I don’t have the brain power to crank out 2,000 fresh words. So here’s a dated piece about Baby Boomer navel gazing and ressentiment.

Thirty years ago this week two million people joined hands forming a human chain across 676 kilometers of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Known as the

Thirty years ago this week two million people joined hands forming a human chain across 676 kilometers of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Known as the  I’ve just come back from a lovely vacation in Ireland. We did a lot of driving and usually had the radio on, often to RTE, the state run station (the equivalent to the BBC in the UK). At least once an hour an advertisement would come on reminding people that they need to get a TV license, which costs 160 Euros, $177 a year. I grew up in the UK, where a license is 154.50 sterling, $187 a year, and remember the ads when I was a child that warned of the TV detector van coming around and catching people who hadn’t paid their license. Of course, that was in the days of very obvious exterior antennas on houses. When TV licenses were first issued in the UK after the second world war, they funded the single BBC channel. Even when I was a child, there were only 3 channels, then when I was a teen 4, and two of those were the BBC. In the UK today, a license is needed for any device that is

I’ve just come back from a lovely vacation in Ireland. We did a lot of driving and usually had the radio on, often to RTE, the state run station (the equivalent to the BBC in the UK). At least once an hour an advertisement would come on reminding people that they need to get a TV license, which costs 160 Euros, $177 a year. I grew up in the UK, where a license is 154.50 sterling, $187 a year, and remember the ads when I was a child that warned of the TV detector van coming around and catching people who hadn’t paid their license. Of course, that was in the days of very obvious exterior antennas on houses. When TV licenses were first issued in the UK after the second world war, they funded the single BBC channel. Even when I was a child, there were only 3 channels, then when I was a teen 4, and two of those were the BBC. In the UK today, a license is needed for any device that is

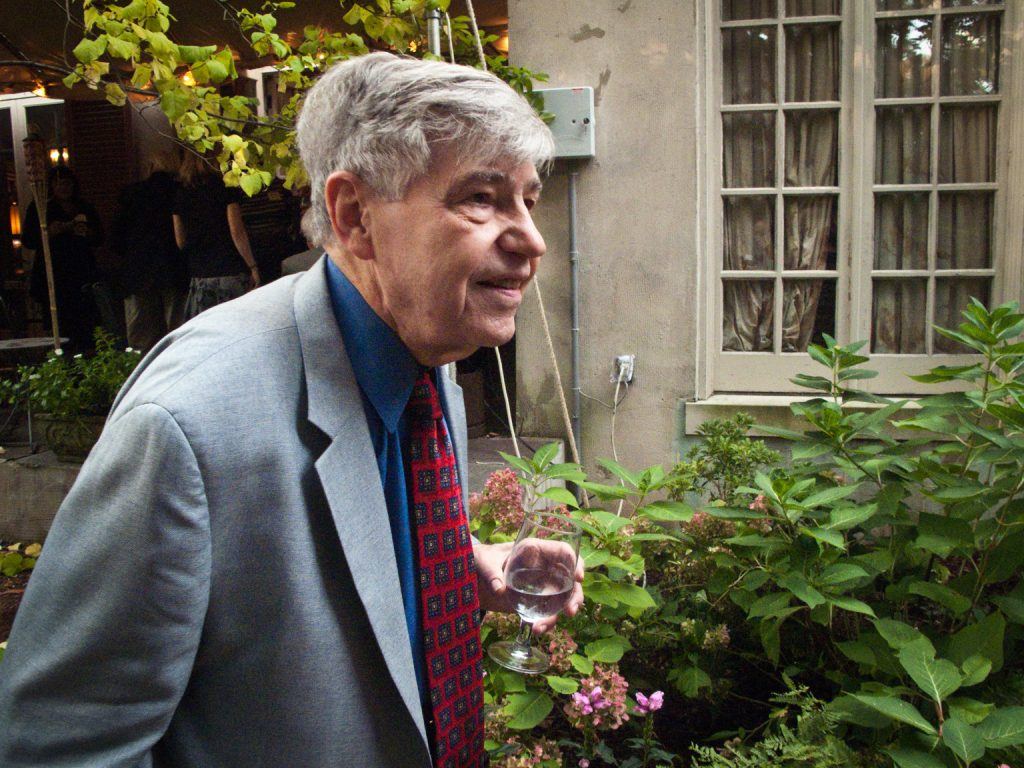

The community of philosophers is mourning the loss of Barry Stroud, one of the great philosophers of the past half-century, who died on Friday, August 9 of brain cancer. Stroud earned his B.A. from the University of Toronto and his Ph.D. from Harvard University. From 1961 he taught at the University of California, Berkeley, where I knew him during my time as a graduate student there.

The community of philosophers is mourning the loss of Barry Stroud, one of the great philosophers of the past half-century, who died on Friday, August 9 of brain cancer. Stroud earned his B.A. from the University of Toronto and his Ph.D. from Harvard University. From 1961 he taught at the University of California, Berkeley, where I knew him during my time as a graduate student there.

I live and work in two different cities; on the commute, I continuously ask my phone for advice: When’s the next train? Must I take the bus, or can I afford to walk and still make the day’s first meeting? I let my phone direct me to places to eat and things to see, and I’ll admit that for almost any question, my first impulse is to ask the internet for advice.

I live and work in two different cities; on the commute, I continuously ask my phone for advice: When’s the next train? Must I take the bus, or can I afford to walk and still make the day’s first meeting? I let my phone direct me to places to eat and things to see, and I’ll admit that for almost any question, my first impulse is to ask the internet for advice.

To follow the popular discourse about the gender wage gap in the United States is to confront perpetual confusion. It is a confusion created at least in part by pronouncements of the type many of us have heard: “Women are paid only 82 cents for every dollar men earn! It is high time for women to earn equal pay for equal work!” Two sentences, each true standing alone, but in juxtaposition creating the impression that the

To follow the popular discourse about the gender wage gap in the United States is to confront perpetual confusion. It is a confusion created at least in part by pronouncements of the type many of us have heard: “Women are paid only 82 cents for every dollar men earn! It is high time for women to earn equal pay for equal work!” Two sentences, each true standing alone, but in juxtaposition creating the impression that the