by Scott Samuelson

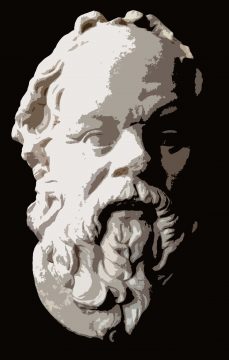

I was a freshman in college when I first read Plato’s Apology, his version of the event that probably made the biggest mark on him: his city’s trial and condemnation of Socrates.

I recall how a fellow student in Humanities 101 was skeptical of the claim in the Apology that the unexamined life is not worth living. He asked about the worth of the lives of the world’s two heaviest twins, the ones pictured on Honda motorcycles in the Guinness Book of World Records (an image emblazoned on all our minds). Regardless of if they led examined lives, he asked, didn’t they seem to be living well, zooming around the country together?

We ended up debating if philosophy is just one way of having a good life, or if it’s a necessary ingredient in all lives. I don’t remember where I landed (in fact, I’m still making up my mind), but I vividly remember thinking that all of us have bottomlessly deep lives, and that all human lives are worth examining, especially those of the two brothers on their Hondas.

I went on to major in philosophy and eventually to teach philosophy in a wide variety of venues—not just liberal arts colleges, universities, and community colleges, but houses of worship, bars, prisons, and even online. I’ve often had occasion to assign the Apology and debate the merits of the examined life.

In my experience, readers of the dialogue are inevitably struck by how Socrates doesn’t seem to care about winning his case. So, what’s he really up to? It’s a question I’ve been thinking about in light of higher education’s current predicament, where the academic humanities are fighting for their existence against powerful economic, cultural, and political forces. What should I as a defender of the humanities be doing? What can I learn from Socrates at his trial?

Having just reread the Apology, this time for the Catherine Project with a group of especially sharp readers, I’ve drawn nine lessons from how Socrates, in a far more perilous situation than our current one, presents and defends the humanities. Read more »