by David Kordahl

Twenty years after Steven Pinker argued that statistical generalizations fail at the individual level, our digital lives have become so thoroughly tracked that his defense of individuality faces a new crisis.

When I first picked up The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature (Steven Pinker, 2002), I was in my early twenties. The book was nearly a decade old, by then, but many of its arguments were new to me—arguments that, by now, I have seen thousands of times online, usually in much dumber forms.

In The Blank Slate, Pinker argued that humans are wired by evolution to make generalizations. These generalizations often lead us to recognize statistical differences among human subgroups—average variations between men and women, say, or among various races. Pinker showed that these population-level observations—these stereotypes—are often surprisingly accurate. This contradicted the widespread presumption at the time that stereotypes must be avoided mainly due to their inaccuracy. Instead, Pinker suggested that stereotypes often identify group tendencies correctly, but fail when applied to individuals. The argument against stereotyping, then, should be ethical rather than statistical, since any individual may happen not to mirror the groups that they represent.

Midway through reading The Blank Slate, I went to the theater to watch Up in the Air (2009), in which George Clooney portrayed a Gen-X corporate shark. At one point, Clooney advised his horrified Millennial coworker to follow Asians in lines at airports. “I’m like my mother,” he quipped. “I stereotype. It’s faster.”

This got a big laugh. We didn’t know, then, that Clooney—with his efficiently amoral approach to human sorting—represented our own algorithmic future.

Life in 2010 was still basically offline. But as members of my generation moved every aspect of our lives onto the servers, it became steadily easier to identify individuals by their various data tags. Dataclysm: Who We Are (When We Think No One’s Looking) (Christian Rudder, 2014) was assembled by one of the co-founders of the dating website OkCupid. It generalized wildly about differences among various racial groups, but no one could accuse the book of simple racism. Tech founders, after all, have large-number statistics to back up their claims—the very patterns that Pinker suggested were natural for humans to perceive, now amplified by enormous datasets and the sophisticated tools of data science.

Later in that decade, the concept of an “infohazard” became popular among online rationalists. The paper “Information Hazards: A Typology of Potential Harms from Knowledge” (Nick Bostrom, 2011) cataloged various harms that could result from knowledge, ranging from examples as quotidian as movie spoilers, to others that could lead to the end of life itself (e.g., physics → nukes).

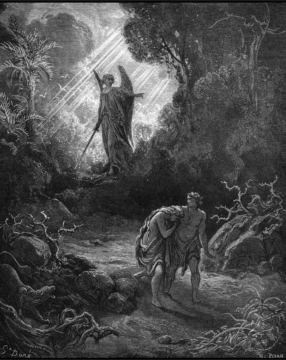

Of course, even if the “infohazard” terminology was new, the idea that information can hurt you was ancient, tracing its roots all the way back to Adam and Eve, who, having gained the knowledge of good and evil, were banished from paradise. The possibility that others can be understood in shorthand via their identity markers seems both plausible, and like an obvious moral hazard.

The world I was born into was limited to TV, radio, and newsprint, but residents of that world had already worried for decades about information overload. In retrospect, this seems quaint. Even in 2010, I suspected that my own habits of thought had diverged sharply from those of my elders, and that this wasn’t entirely a good thing. By now, these trends have amplified once again.

Recall that in 2002, Pinker could argue that no individual could be characterized just by tracking their group memberships. This seemed persuasive at the time, but is less so in 2025. Young adults now scatter their data all day long, and it isn’t hard to imagine a panoptical statistician collecting these digital breadcrumbs to construct a rich, predictive map of an individual’s life, complete with encoded information about when they wake and sleep, what language they use, which apps they scroll, what music they stream. This would extend even to their emotional life—what makes them laugh, what makes them angry, what turns them on.

The metaphysical question, I suppose, is whether, beyond all these trackable correlations, some residue of individualism remains—an extra part that can’t be captured with prefab categories. Perhaps we should consider it a moral imperative to act as though an irreducible self exists, even as this stance becomes ever more difficult to maintain beneath the growing digital shadow. Even outside the garden of ignorance, we might learn to respect what algorithms cannot see.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.