by Rafaël Newman

This year marks the 80th anniversary of the end of the Third Reich, and thus of the industrialized mass murder known as the Holocaust, or Shoah—although 1945 was not the end, according to Timothy Snyder, of World War Two. That conflict, the historian maintains, was pursued by the otherwise victorious imperial powers in their respective independence-minded colonies, and only concluded with those powers’ defeat and withdrawal, or with the substitution of some variety of “post-colonial” economic system (The Commonwealth, La francophonie) for classic empire. To say nothing of the “mercantilist neo-imperialism” currently looming.

This year marks the 80th anniversary of the end of the Third Reich, and thus of the industrialized mass murder known as the Holocaust, or Shoah—although 1945 was not the end, according to Timothy Snyder, of World War Two. That conflict, the historian maintains, was pursued by the otherwise victorious imperial powers in their respective independence-minded colonies, and only concluded with those powers’ defeat and withdrawal, or with the substitution of some variety of “post-colonial” economic system (The Commonwealth, La francophonie) for classic empire. To say nothing of the “mercantilist neo-imperialism” currently looming.

In any case, eight decades after 1945, there are fewer and fewer survivors of the Nazi regime still alive—a recent publication, urgently entitled Bevor Erinnerung Geschichte wird (“Before memory becomes history,” 2022), contains interviews with a remaining handful of eyewitnesses to the Shoah. Today, with well-publicized settlements (or at least public investigations) of notorious thefts by the Third Reich such as those involving the “Nazi gold” transports, “dormant” bank accounts, and the Bührle Art Collection in Zurich, literary commemoration of the period has begun to turn from lived human suffering to what has been (or might have been) left to succeeding generations: to what has been materially bequeathed, in distinction from the traumatic psychological legacy of second and third-generation survivors. Increased attention is being paid to the physical estates of the victims of terror and genocide; to the belongings that were stolen from them, lost, or destroyed; to the property that individual members of targeted populations were obliged to leave behind, to sell for a pittance, or to have forcibly auctioned off. As if, having dealt comprehensively with the Third Reich’s violations of the Sixth Commandment—“Thou shalt not kill”—we have moved on to a reckoning with its infringements of the Eighth—“Thou shalt not steal.” Is any form of individual compensation, of making-good-again still possible, now that the physical and mental suffering of the victims has been largely acknowledged, their deaths publicly mourned? What would a literary performance of the acknowledgment of theft, and reparations for it, look like?

One example comes from an author born in what was then the German Democratic Republic, whose career as a writer began following the unification of the two Germanies, and who, although not a member or descendant of either the perpetrator or victim groups of the Shoah, is personally acquainted with the consequences of Germany’s 20th century. In Heimsuchung (2008; Visitation, 2010), Jenny Erpenbeck chronicles the vicissitudes of the country house on a lake near Berlin where she spent her childhood summers as it passes from owner to owner, from inhabitant to inhabitant over the course of a century; Erpenbeck uses the house and its residents to relate the history of Germany from the 1800s to the post-Wall period. (The novel begins, however, in prehistory, with the formation of the Brandenburg terrain after the Ice Age, and features the reappearance between chapters of an uncanny, ageless groundskeeper, the better to set all the ensuing episodes of human inhabitance in perspective.) Inspired in part, perhaps, by W.G. Sebald’s Luftkrieg und Literatur (1999; On the Natural History of Destruction, 2003), with its call for a literary reckoning with the consequences of the Third Reich for all concerned, Erpenbeck gives an account of the suffering endured not only by the victims of the Nazi regime, but also, in the aftermath of Germany’s defeat, by its perpetrators and their descendants.

One example comes from an author born in what was then the German Democratic Republic, whose career as a writer began following the unification of the two Germanies, and who, although not a member or descendant of either the perpetrator or victim groups of the Shoah, is personally acquainted with the consequences of Germany’s 20th century. In Heimsuchung (2008; Visitation, 2010), Jenny Erpenbeck chronicles the vicissitudes of the country house on a lake near Berlin where she spent her childhood summers as it passes from owner to owner, from inhabitant to inhabitant over the course of a century; Erpenbeck uses the house and its residents to relate the history of Germany from the 1800s to the post-Wall period. (The novel begins, however, in prehistory, with the formation of the Brandenburg terrain after the Ice Age, and features the reappearance between chapters of an uncanny, ageless groundskeeper, the better to set all the ensuing episodes of human inhabitance in perspective.) Inspired in part, perhaps, by W.G. Sebald’s Luftkrieg und Literatur (1999; On the Natural History of Destruction, 2003), with its call for a literary reckoning with the consequences of the Third Reich for all concerned, Erpenbeck gives an account of the suffering endured not only by the victims of the Nazi regime, but also, in the aftermath of Germany’s defeat, by its perpetrators and their descendants.

Hanging over the entire book, nevertheless, is the fact that the house was once owned by certain of those victims. Among the early episodes is that of the Kaplans, the Jewish family obliged to sell the property in the 1930s in a vain effort to escape the coming catastrophe. Heimsuchung is dedicated to Doris Kaplan, the family’s young daughter, about whom Erpenbeck learned in the archives during her work on the book, and who she knows was murdered by the Nazis. Doris’s death at a concentration camp and burial in a mass grave is among the novel’s most painful chapters, which ends with the observation that no one will ever again call her name—and with Erpenbeck’s explicit (and, in a book of largely nameless characters, striking) invocation of that name.

In the course of her research, Erpenbeck also learned of the auctions of property confiscated or bought well below market value from fleeing Jewish Germans, in some cases awarded by the authorities (for a discount) to particularly loyal accomplices. The lake house thus becomes the sign of the Nazis’ material crime of dispossession, which accompanied their spiritual crime of genocide. The two crimes are, however, not entirely distinct. In an interview, Erpenbeck has noted that, in her reconstruction of the “imaginary history” of this actual historical estate, the physical space of the house also represents, for young Doris, “practically the entire world that she has lost”—her Heimat, that German word which means at once physical home and spiritual homeland. And when in that same interview Erpenbeck displays the deed of sale she discovered in the archives, which had been salvaged from a dumpster by a conscientious ex-GDR official in the 1990s, she makes explicit the importance of a written record of ownership, both bureaucratic and literary, to the project of memory: “Wer nicht im Grundbuch steht hat das Grundstück auf jeden Fall verloren.” If you’re not in the registry, you’ve certainly lost the property: the German composite terms “Grundbuch”—ground-book—and “Grundstück”—piece of ground—make poignantly clear the existential link between writing and ownership, and render Erpenbeck’s book a posthumous re-assignment of belonging to the dispossessed.

In a reckoning with Nazi theft still more personal than Erpenbeck’s, Nadine Olonetzky, an acclaimed art critic and author, relates her Jewish-German father’s decades-long attempt to obtain reparations from the Federal Republic of Germany for the property his family was forced to leave behind when they fled the Third Reich. Wo geht das Licht hin, wenn der Tag vergangen ist (2024; “Where does the light go when the day is over,” English translation forthcoming) is an exhaustive, enraged, utterly human account of Olonetzky’s research, in archives and interviews, as she reconstructs her refugee father’s battle with German bureaucracy from his home in Switzerland.

In a reckoning with Nazi theft still more personal than Erpenbeck’s, Nadine Olonetzky, an acclaimed art critic and author, relates her Jewish-German father’s decades-long attempt to obtain reparations from the Federal Republic of Germany for the property his family was forced to leave behind when they fled the Third Reich. Wo geht das Licht hin, wenn der Tag vergangen ist (2024; “Where does the light go when the day is over,” English translation forthcoming) is an exhaustive, enraged, utterly human account of Olonetzky’s research, in archives and interviews, as she reconstructs her refugee father’s battle with German bureaucracy from his home in Switzerland.

Olonetzky’s father had told her on just one occasion, when she was a teenager in the 1970s, about the murder of her grandfather and aunt by the Nazis, and of his own perilous flight across the Swiss border. Years later, in 2019, Olonetzky decided to have Stolpersteine, “stumbling blocks” or memorial stones, set in the pavement in Stuttgart, her Jewish ancestors’ former home, to mark their onetime presence there, and the violence they suffered at the hands of the Nazis. When she applied for official records of her family in Germany, as required by the director of the Stolpersteine project, Olonetzky received not only proof of their residence in Stuttgart, but also thousands of pages of correspondence between her father, Benjamin Olonetzky, and the authorities: documentation of his continually frustrated campaign, over some 20 years following the end of the Reich, for acknowledgment of the murder of his father and sister, for recognition of his own suffering as a slave laborer—and for compensation for the theft of his family’s belongings.

What Benjamin Olonetzky was ultimately granted by the FRG—a few thousand Deutsche Mark, to be shared with his siblings—bore no relation to either the lost property in question, or to his years of humiliation by German officials. One of the great (and chilling) literary feats of Olonetzky’s book is her meticulous juxtaposition of the verbatim responses her father received from a succession of bureaucrats with her own vivid and lyrical prose. The provincial administrators Benjamin corresponded with produce the most desiccated officialese, a German riddled with abbreviations and euphemisms and couched mainly in impersonal constructions and the passive voice. For her part, Olonetzky, whose distinguished career as a critic has been devoted to both photography and the history of gardening, writes with warmth and directness, mingling Yiddish phrases and Jewish jokes—some of these last invented ad hoc—with a chronicle of the seasonal vegetation that surrounds her in her unalienated Swiss habitat, as well as with the occasional frank outburst of scorn or outrage. When for example in 1952 the German officials refuse to consider Benjamin’s request for indemnification for property seized without his father’s official death certificate, and Benjamin explains that Moritz Olonetzky, born May 1, 1881, in Odessa, was deported from his home in Stuttgart to a camp in or near Lublin in 1942, and has not been heard from since, a certain Oberamtsrichter Stahl issues an order for Moritz to appear in Room 180 of the Stuttgart District Court by September 15, 1953—for which act he bills Benjamin DM 2.50. Nadine’s reaction as she reads this grotesque letter is to laugh out loud—and to cite a popular song, in Swiss dialect, about the absurdity of bureaucratic language.

In an epilogue, Olonetzky explains her use in the book of snatches of both Yiddish and Swiss-German, dialects of the same linguistic family, which she cherishes for their respective and contradictory representations of exile across many nations, and of intimacy within one eclectic cultural sphere: for their status as minority languages, which automatically renders them resistant to the deadening clichés of “High German,” the “master” tongue.

In her turn, Olonetzky has thus also re-assigned ownership of lost property to the dispossessed through the act of writing, through the creation of her own idiosyncratic Grundbuch in the absence of her family’s Grundstück. But she does not, for all that, call for peace and reconciliation with Germany’s post-war administrators of stolen property, a generation of cold-blooded fences whom she excoriates, in one memorably indignant passage, as “damned bloodsuckers.” In The Safekeep (2024), meanwhile, the most literary of these recent accounts of property restitution—most literary because historical fiction rather than archival reconstruction or memoir—Yael van der Wouden does imagine a possible reconciliation: if not with the actual, active perpetrators of wholesale murder and theft, nor with their epigones, then at least with the receivers of the spoils.

Set in the early 1960s in the Dutch provinces, The Safekeep evokes the paradoxical atmosphere of burgeoning modernity and repressive traditionalism that characterized the postwar Netherlands. Van der Wouden, who was born in 1987 and is of Israeli and Dutch descent, builds her novel on historical research into the reception of Dutch-Jewish survivors returning to Holland after the Shoah and seeking to reclaim their forcibly abandoned property. She was moved to write the book, she explains in an afterword, by the deaths of her grandparents, and considers it a “parting gift.” The novel thus implicitly marks the passing of the survivor generation while also staging an (imaginary) accounting with their tormentors: by setting her story just a decade and a half after the end of the Shoah, van der Wouden reanimates a world in which protagonists on both sides of the divide are still very much alive, and capable of reckoning with one another.

Set in the early 1960s in the Dutch provinces, The Safekeep evokes the paradoxical atmosphere of burgeoning modernity and repressive traditionalism that characterized the postwar Netherlands. Van der Wouden, who was born in 1987 and is of Israeli and Dutch descent, builds her novel on historical research into the reception of Dutch-Jewish survivors returning to Holland after the Shoah and seeking to reclaim their forcibly abandoned property. She was moved to write the book, she explains in an afterword, by the deaths of her grandparents, and considers it a “parting gift.” The novel thus implicitly marks the passing of the survivor generation while also staging an (imaginary) accounting with their tormentors: by setting her story just a decade and a half after the end of the Shoah, van der Wouden reanimates a world in which protagonists on both sides of the divide are still very much alive, and capable of reckoning with one another.

The Safekeep is a meditation on the significance of place and property in the formation of an identity, and the psychological dangers of repressed memory. The minutiae of the plot—at stake initially are cutlery and crockery, among other items, and the dénouement turns on a mislaid diary—remind us, in the emotional explosiveness of the novel’s resolution, of the outsized importance of apparently banal and domestic features to the construction of a home, or Heimat. As well as of the necessity of being able to lay claim to that home by presenting a Grundbuch, and the possibility of writing that ground-book anew, and thus healing the wound inflicted by invasion, occupation, and mass murder.

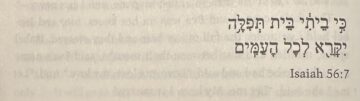

Van der Wouden concludes her novel with a citation from the Torah: For my house will be called a house of devotion for all, Isaiah 56:7. Seen by the non-Jewish protagonist on the wall of a synagogue in her town in the book’s final chapter, the citation, written in Hebrew, is at first illegible, until she locates the passage in her Dutch Bible at home. When the novel ends, a few pages and one remarkable scene of hope reborn later, the citation is printed following the final words of narration—“a gift”—but now in the originally inscrutable Hebrew:

“For my house will be called a house of devotion for all”: The novel’s protagonist echoes the key words (“my house, my house, my house” and “devotion devotion devotion”) as she prepares the reconciliation, both personal and political, with which the novel ends. Van der Wouden’s historical reconstruction thus goes furthest of these three works towards restoring both stolen property and devastated humanity: because it is a fiction, a virtual manifesto for the recreation of relations among human actors set against one another by forces of violence—ethnonationalist, ideological, patriarchal—beyond their control.

Meanwhile, of course, in the historical, non-fictional world, the violence continues, as the regime currently controlling Israel, one of van der Wouden’s two countries of origin, pursues its murderous policies under the pretext of combating the violence it has conspired to engender. The death and destruction of property and infrastructure being visited on Palestinians by Netanyahu’s government and the Israel Defense Forces in what must certainly be considered, in Snyder’s terms, a distant continuation of postwar colonialism will surely one day call for its own works of historical accounting. But whether reconciliation can ever be achieved, actually or fictionally, seems like a very remote possibility indeed.

Margarete Susman, the German-born Jewish thinker who reflected on homelessness in her philosophy and poetry, and who found a Heimat, physically, in Swiss exile, and spiritually in her relations with other thinkers, published a fiery reckoning with the Shoah and its consequences immediately after the end of the Nazis’ genocidal system. In Das Buch Hiob und das Schicksal des jüdischen Volkes (1946, “The Book of Job and the fate of the Jewish people”), Susman re-reads the Biblical account of Job’s trials as an inquiry into the possibility of divine justice, and uses it to insist on the necessity of remaining sanguine and committed to humanity, and to the hope for a healing of the rifts in creation through a commitment to an open-ended messianism, which she identifies as the central work of the Jewish tradition.

In a preface to the second edition of her book, however, published in 1948 shortly after the founding of the state of Israel, Susman voices an anxious skepticism in the face of the Zionist project, insofar as it is identified with the fate of the “Jewish people” in general:

But with this warlike defense, as with the state which requires it, the people has absorbed a piece of the chaos alien to it, and thus endangered its internal existence more seriously than its external. By pursuing this way of life, it is participating in the bloody confusions and distortions of the world of nations so deeply anathema to it; it is participating in the curse of nationalism, in the growing petrification of life, in the apocalyptic cooling of hearts that is cooling the life of humanity. Can the messianic legacy still be managed in such a reality? Is it still possible—and this is the same question—to bring the simply human to fruition?

Susman’s questions remain unanswered—that is, if the “Jewish people” continues to be identified with the state of Israel. What is certain is that there can be scant hope of a house of devotion for all in Gaza, where fewer and fewer houses of any kind stand, and where the murder of civilians continues unabated, despite the ceasefire. How can a Grundbuch be recreated when there is no ground left to write it on, and no one left to read it?