by Usha Alexander

[This is the twelfth in a series of essays, On Climate Truth and Fiction, in which I raise questions about environmental distress, the human experience, and storytelling. All the articles in this series can be read here.]

In the late 1960s and early 70s, Pocatello, Idaho, was one of the fastest growing towns in the United States. It was, and still is, a bland little place in the arid montane region of the American West. I don’t know why it mushroomed then; it has since stagnated and even shrunk. Nevertheless, the summer I turned four, my family was one among many who moved to reside there. Our little red brick house, still unfinished on the day we moved in, was the last house at the end of a newly laid street, still half-empty of houses. Our street stretched like a solitary finger into a kind of wilderness, an austere, high-desert landscape that surrounded our foundling residential colony. From my vantage as a child, preoccupied with the flowers, spiders, and thistles that stuck to my socks, I would see this place transformed.

In the late 1960s and early 70s, Pocatello, Idaho, was one of the fastest growing towns in the United States. It was, and still is, a bland little place in the arid montane region of the American West. I don’t know why it mushroomed then; it has since stagnated and even shrunk. Nevertheless, the summer I turned four, my family was one among many who moved to reside there. Our little red brick house, still unfinished on the day we moved in, was the last house at the end of a newly laid street, still half-empty of houses. Our street stretched like a solitary finger into a kind of wilderness, an austere, high-desert landscape that surrounded our foundling residential colony. From my vantage as a child, preoccupied with the flowers, spiders, and thistles that stuck to my socks, I would see this place transformed.

Little did I know that this landscape was, in fact, already overgrazed and degraded, that some of the plants, which so quickly became familiars—like the Russian Thistle, aka tumbleweed—were actually invasive species. Despite that, it thrived. The undulating hillsides were coarsely matted with hard grasses and sedges, sagebrush, gnarled juniper, all hues of dusty green and wood. Here and there, yellow flares of prickly pear blossoms. Blood red Indian paintbrush splashed across the pale dirt. A sprinkling of white sego lilies.

All the new, single-story homes along our street were encircled by large, grassy yards, where the neighborhood kids played for hours into the lingering, northerly summer sunsets. Next to our house, a dusty trackway wound down the hillside toward a rustic, little ranch below. A brook that passed by the ranch could be made out by the vibrant streak it traced through the pale grasses and shrubs, an incongruous density of ferns and spindly, deciduous trees that grew up from its steep banks. A set of fences out beyond the dirt road sometimes corralled a few horses or cows. Alongside them, a scratch of a trail led further up into the open hills.

I never thought of this landscape as beautiful, but spare and stark, almost frightening. At the same time, I somehow understood it to be connected to me and everything else, something absolutely real, essential and alive, in a way that was apparent even to a child. In the early years, my sister, my best friend, and I went through a phase of bowing in gratitude to the trees, speaking to them almost as our elders, though no one had taught us to do this. We used to wander for hours on foot and found our first taste of adventure in spotting shy foxes or bounding hares or golden eagles. My whole childhood smelled like sagebrush and juniper and dust, with occasional wafts of cowshit from the nearby corrals. At night, the melancholy howls of coyotes in the nearby hills pierced the darkness, as did the hoots of trains passing through the city’s downtown depot. That the wilderness represented something far greater than us was plainly obvious when we were young; but our awareness was somehow turned away from this knowledge as we grew.

By the time I was in junior high school, the tumbleweeds and Indian paintbrush and fox dens were gone. The dust paved over. The brambly creek buried. The coyotes silenced. The hillsides covered with houses under construction, now two stories high. The prickly pears exchanged for clipped lawns and tulip beds. All of this made me ineffably sad and anxious. My family moved to a bigger house, far beyond the expanding edge of town. The new road we lived on remained rural, but also tripled from two to six houses (including ours), by the time I graduated high school. And the town proper continued to sprawl, its population more than tripling since the time of my family’s arrival, to harbor some sixty-five thousand souls.

Years later, I would notice how blithely people presume that whatever humans do has at most a minuscule effect upon the state of the planet and its living systems; but even though I didn’t yet have the language or data to explain why or how, I already knew this wasn’t true. I’d seen how much space human beings take up in this world, how absolutely everything else gets swept aside, without consideration, to make place for whatever we build. I witnessed how quickly our ordinary desires and actions can amount to something that overwhelms the wellbeing of the non-human world, how much is displaced by what we take up, that there really is a kind of zero-sum game of life. Even this seemed fine, up to a point, so long as some kind of balance was maintained. But it was clear that there was no balance between the human and non-human worlds: one of these was resolutely displacing the other.

I remember learning in the fifth grade that the world’s population had doubled since just a few years before I was born, and it was set to double again, even faster. Knowing this worried me. Whenever I brought it up with others over the years, they were always quick to assure me that people would always be able to produce enough food to eat, as if that were the only thing that mattered. And while even that didn’t quite seem like a sensible presumption to me, it wasn’t my primary concern. If there were going to be more and more people, I wondered, what will be left for the non-human world? Indeed, while the human population has exploded, the populations of wild animals and plants have commensurately been crashing. Today, human bodies make up thirty-six percent of the mammalian biomass on the planet; our livestock and pets make up another sixty percent. This means that all the wild mammals on Earth constitute a minuscule four percent. Though we are only one among some sixty-five hundred extant mammalian species and one among thirty-five thousand terrestrial vertebrate species, between 1970 and 2018, we’ve been directly responsible for twenty-eight percent of the deaths among wild animals with whom we share the land; that proportion goes up, perhaps incalculably, if you include deaths by habitat destruction, let alone if you include domesticated animals. Each year, humans directly or indirectly (through our domesticated animals), consume, co-opt, or destroy almost forty percent of the planet’s annual net primary productivity (the amount of sunshine that annually falls to Earth and gets converted by plants into the carbon bonds that provide all the energy used by the rest of the biosphere). That’s to say: our single species appropriates an egregiously outsized portion of the energy available to fuel the entire biosphere, a situation that’s clearly wildly out of balance and unsustainable. It’s ludicrous to maintain the politically correct pretense that there is no such thing as human overpopulation, no matter how you slice up our consumption patterns among countries or classes.

And worse: In addition to this direct energy gluttony, humans also annually consume hundreds of years’ worth of ancient net primary productivity, available to us in the form of fossil fuels. Such an imbalance in the use of planetary resources and such a profound reshaping of energy flows for the purpose of maintaining the expanding lifestyle of a single species is bound to warp the Earth system in multiple ways, including the very ways we’re presently witnessing, from mass extinction to pollution to climate change. The decline of non-human species is of such a magnitude and speed that an event of this kind has occurred only five times previously in planetary history; only the fall of the meteor that ended the dinosaurs has precipitated a faster rate of extinctions.

Human Blight or Human Plight?

There has been, of late, a growing sensibility regarding the environmental damage that the human enterprise continues to wreak upon the Earth. This is mostly a narrow awareness about climate change and the way planetary heating will affect the functioning of our modern global civilization. Some concern has also surrounded the extinction of a few celebrity species, like whales, lions, elephants, and rhinos. Talk of conserving species primarily centers on the animals of Africa, a place that many of us who grew up outside of wish to remain wild, even as the rest of us go on destroying our own wild spaces to pave new roads and build new residential colonies and shopping complexes for our own convenience and enjoyment.

At the same time, it’s also true that this growing concern about the non-human world—what we like to call Nature—has led some of us to believe that human beings are inevitably bad for the planet, something like a cancer upon this Earth. We’re destroying god’s creation, some lament; we’ve not been the stewards of Nature that god expected us to be. Even most who eschew such Abrahamic terms in regretting our modern ecocide still take it for granted that the human clash with Nature is somehow an inescapable quality of being human. In response to this, perhaps, one idea gaining traction is the notion that the only way for our species to stop destroying our world may be to transcend being human, altogether, by integrating ourselves into our technology, which, by some fantastical rationale, is presumed to be a more perfect and resource-independent state of being—imagined as more godlike perhaps because it’s un-Natural, or supra-Natural.

But all of this reasoning begins with at least one fundamental flaw: it rests upon forgetting that human beings are, in fact, a part and product of the Natural world, every bit as much as pond scum and chipmunks and coral reefs and combustible fossils. We aren’t, in fact, in any way separate in our source, creation, maintenance, or ultimate trajectory from the rest of Nature. We may think ourselves a particularly clever species, but we are still subject to the same laws, limitations, potentialities, and mysteries as everything else. The Earth produced us, and we belong to it every bit as much as all the other life forms with whom we cohabit this planet. All the evolution that preceded us played a part in creating us by producing the world we were born into—all of the unique and astonishing creatures and landforms and chemical cycles that facilitated our arrival and support our continued existence as human beings, by forming the complex and flexible niche to which we adapted. And we also play a part, like every other lifeform, exerting a presence that shapes the planet and the biosphere, co-creating the world that all other creatures are born into.

Humans have been altering our environments for a very long time. We are, like all other creatures, active participants in the web of life, a web defined not merely by who eats whom, but how organisms and communities interact in multiple ways. The integrity of the web of life is a matter of balance and reciprocity, along uncountable avenues in constant flux—including many we are not yet, and may never become, aware of. Indeed, there is very little about life, as a force or element or aspect of the cosmos, that we do understand. But one evident law of life, seemingly incontrovertible, is that nothing lasts forever; everything changes. Every living species that has ever come into existence has gone, or will go, out of existence, either at an evolutionary dead end or by evolving into another sort of creature. We can be no exception to this law of life. So win, lose, or draw, we will only play our part in setting the stage for whatever comes after us.

And yet, if the web of life depends upon balance, something is certainly off-kilter in the world under human influence. No species can “win” this zero-sum game of life, as we are trying to do. In this way, there’s really something different about the way our planet is changing, during our present age of human planetary dominance, compared to any other time in at least the past few billion years: it might be the first time in epochs that a single lifeform has had such a tremendously transformational effect over the entire Earth. Our species, alone, is responsible for changes that reach so deeply into the networked processes of our Earth system that they are already resulting in a system-wide rewrite of environmental conditions. We are blithely and repeatedly tapping the Delete button across the biosphere. And oops—there’s no Undo!

But we’re not the first species ever to have done this; it happened at least once before, in the earliest epoch of life on our planet around four billion years ago. There were far fewer forms of life at that time, all of them single-celled organisms floating in the anoxic stew of Earth’s watery surface. As they mutated, proliferating in brand new forms, evolving to take advantage of the open niches—as yet undiscovered ways of life—one of them was born who pooped out oxygen as a metabolic waste product. This creature, cyanobacteria, did very well, much to the aggravation of its neighbors, who preferred the anoxic environment they were adapted to. Still, it was fine at first: the buildup of free oxygen was geologically slow, and mostly clung to the rocks, turning Earth’s newborn iron rust-red, maybe giving the world ocean a lurid cast. But over billions of years, as oxygen-polluting cells multiplied, atmospheric oxygen eventually accumulated, in what we now call the Great Oxygenation Event. The oxygenated atmosphere caused the extinction of many anaerobic forms of life, by around two and a half billion years ago, making the world an entirely different place. The stage was now set for the takeover by other cells, who had been quietly expanding through the ruddy waters, evolving to take advantage of plentiful free oxygen, rather than die in it. What followed was the rise of all the lineages of living things that thrive under a blue sky: life as we know it.

But we’re not the first species ever to have done this; it happened at least once before, in the earliest epoch of life on our planet around four billion years ago. There were far fewer forms of life at that time, all of them single-celled organisms floating in the anoxic stew of Earth’s watery surface. As they mutated, proliferating in brand new forms, evolving to take advantage of the open niches—as yet undiscovered ways of life—one of them was born who pooped out oxygen as a metabolic waste product. This creature, cyanobacteria, did very well, much to the aggravation of its neighbors, who preferred the anoxic environment they were adapted to. Still, it was fine at first: the buildup of free oxygen was geologically slow, and mostly clung to the rocks, turning Earth’s newborn iron rust-red, maybe giving the world ocean a lurid cast. But over billions of years, as oxygen-polluting cells multiplied, atmospheric oxygen eventually accumulated, in what we now call the Great Oxygenation Event. The oxygenated atmosphere caused the extinction of many anaerobic forms of life, by around two and a half billion years ago, making the world an entirely different place. The stage was now set for the takeover by other cells, who had been quietly expanding through the ruddy waters, evolving to take advantage of plentiful free oxygen, rather than die in it. What followed was the rise of all the lineages of living things that thrive under a blue sky: life as we know it.

Needless to say, for a single type of organism to play such an outsized role in refashioning the world environment is a rare and dangerous game. The Great Oxygenation Event was a catastrophic turn for most of life on Earth at the time. I don’t know that any other life form ever had an effect quite like that again—perhaps not until now, with our mass burning of fossil fuels, planetary scale habitat destruction, and petrochemical farming. But it does not follow from these examples that environmental changes caused by living things are necessarily detrimental to the biosphere, or that they always create massive disruptions through which even local ecosystems cannot persist. As with most things, it is always a matter of form and degree. And while it’s true that in recent centuries human beings have been pushing the environment too far, it wasn’t always so, and it needn’t continue so.

Human beings and cyanobacteria aren’t the only beings to alter their environments. Consider the beaver or the elephant, both of whom refashion the land, actively shaping the niches in which they live. Beavers famously do this by cutting down trees, pruning the forests, damming and diverting flows of water. Elephants, too, knock over trees, causing nearby river waters to meander in constantly shifting flows. Beavers and elephants have been doing this for millions of years. Gophers, moles, and other animals dig expansive tunnels underground; termites build sturdy mounds. Corals build monumental reefs. All of these things become features of the landscape for years or even decades—in the case of corals, for up to hundreds of thousands of years. And for each of these animal-built features, a host of other organisms co-evolve to take advantage of the conditions that this niche-engineering provides.

Indeed, it must be true that every animal does this at least in small ways that may strike us less obviously. Consider the bee. Does its pollination of flowers not lead to an increase of its most favored/visited kinds of flowers in its nearby environs? Consider the by now well-known case of the wolves in Yellowstone National Park. Decades after wolves had been annihilated in the park, they were reintroduced between 1995–97 and their presence drastically enriched the landscape within three decades, affecting fauna, flora, and the very terrain—the patterns of erosion and meanders of the rivers. The direct effects of bees, wolves, elephants and most other animals are subject to cycles, constantly undone and renewed, intertwined with the cycles of other organisms in their vicinity, moving around a zone of balance. The built works of most animals that erect constructions, like beavers and termites, are transient on geological timescales, not enduring even for centuries. The corals are exceptional in this way, but the reefs they build themselves become foundational structures that anchor entire ecosystems, supporting some twenty-five percent of marine life today. For the most part, animal activities and constructions generally don’t destroy whole communities of life, wipe out entire species by the handful, nor impoverish their local ecosystem in such a way that their surge of disruption endures on geological timescales. In this way, what humans have been doing and building over the past few millennia is fundamentally different from what other animals—and even earlier humans—have done and built.

Transient Niche-Engineering

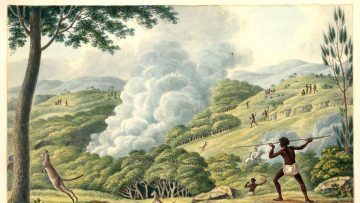

Since Africa is where humans originally came from, the African wilderness is the first place where humans had an environmental impact. Possibly beginning a million or more years ago, controlling fire may have been the first way humans—or our latter-day hominin ancestors, Homo erectus—tried to shape their environment to their purposes at larger scales, in the manner of elephants. Erectus could direct fires to drive game for a hunt. They could employ it to renew growth or expand grasslands, promoting the availability of more tubers and other preferred plant foods, as well as enticing grazing animals to venture nearby for easier hunting. They could use it to keep warm, thus expanding their range into colder territories. They could use it to cook, thus broadening their menus and their palettes, which then also changed what items they harvested from their local environment, and every choice, made at habitual scale, would have cascading effects throughout the local environment.

Even in more recent millennia, fire is well attested as a tool for landscape management among Indigenous peoples from Africa to Australia to the Americas. Some plant species have even come to take advantage of fire for their own propagation—grasses and shrubs that thrive on newly burned ground or trees that use fire to release their seeds. In some parts of Australia, where controlled burning has been regularly practiced for unfathomable millennia, the cessation of traditional burning practices by the modern authorities has left forests vulnerable to devastating wildfires, suggesting that entire forest ecosystems may have come to be dependent on human activity as a natural part of their own wellbeing and preservation. In using fire to optimize our environments, humans, in turn, also became dependent upon fire: Our digestive systems and dentition and skulls are optimized to take advantage of cooked foods. Eating cooked food also enabled the enlargement of our brains. Without fire to cook our food today, we would find little we could eat and properly digest.

Even in more recent millennia, fire is well attested as a tool for landscape management among Indigenous peoples from Africa to Australia to the Americas. Some plant species have even come to take advantage of fire for their own propagation—grasses and shrubs that thrive on newly burned ground or trees that use fire to release their seeds. In some parts of Australia, where controlled burning has been regularly practiced for unfathomable millennia, the cessation of traditional burning practices by the modern authorities has left forests vulnerable to devastating wildfires, suggesting that entire forest ecosystems may have come to be dependent on human activity as a natural part of their own wellbeing and preservation. In using fire to optimize our environments, humans, in turn, also became dependent upon fire: Our digestive systems and dentition and skulls are optimized to take advantage of cooked foods. Eating cooked food also enabled the enlargement of our brains. Without fire to cook our food today, we would find little we could eat and properly digest.

Another way humans learned to engineer their niches, near the beginning of the Holocene, was to practice transhumant pastoralism. Some human bands had long been following goats or reindeer or other ungulates as they migrated along their seasonal grazing routes. They may even have actively cared for the herd, protecting them from other predators, offering aid to the injured, perhaps forming relationships with individual animals. But beginning in the early Holocene, some peoples further intensified this practice, selecting favored animals for breeding, selecting for docility, among other traits. Over hundreds of generations, the animals become more dependent upon humans, too, thriving best under benevolent human care, in a kind of symbiosis we call domestication, even though eventually they would be chosen for slaughter. These early pastoralists remained transhumant—that is, they migrated back and forth between their herds’ native grazing grounds—thus disrupting the local ecosystems far less than if they’d kept the animals penned, concentrated in one area and unable to exert the influence of their seasonal grazing, treading the soil, and manuring, diffused across the wider landscape.

Around the same time, people were also learning to actively propagate their favorite plants. First, this was done in situ, in “the wild,” where gatherers made mental note of what flourished best under which conditions, how quickly harvests were regenerated, what happened when one species became overly dominant in an area, and other useful data that enabled them to promote certain species without collapsing an entire ecosystem. Later on, in some locales, this was done slightly more intensively with swidden horticulture: burning down a small stand of forest and then planting several crops in the ashen patch of ground. Such a garden could be productive for up to a few years, and this might encourage village settlement. Once the garden was exhausted, it was left fallow to be overtaken by the jungle. Swidden gardens were kept small enough that the forest wasn’t effectively fragmented and could readily reclaim the garden space, once it was abandoned. The villagers might then burn a new patch of ground nearby to plant a new garden. Villages created around such systems of shifting horticulture would themselves be abandoned after a couple of years or a couple of decades or perhaps, at most, a couple of generations. Everything built in the village was locally sourced and biodegradable and would return to fertilize the soil from which it came, the forest regenerating over the remains of the old village site, while the people relocated to a fresh site to start over, leaving no permanent damage. Meanwhile, as women selected seeds for their gardening, these too grew adapted to the human touch, some of them eventually requiring human intervention to grow well at all.

There are several other similarly low-intensity environmental engineering practices. One might expand a small backwater along the flow of a river, for instance, where some species of fish and other animals or plants prefer to congregate, which provides better fishing and gathering for the people who maintain the area. Or one might take the stones strewn across a hillside and pile them into low walls to slow the wash of heavy rainshowers, thus reducing erosion, raising the local water table, and greening the hillside with plants you can make use of. As with other animals, all these modes of niche-engineering would ultimately have been transient in nature, subject to the shifts and cycles and behaviors of the weather and the other beings that occupied the same land, some who might even periodically overtake it or revise it according to their own lifecycle agendas. And all of these strategies required practitioners to be flexible in their approach to life, to understand that each community of living things has its seasons and its limits; that they should never take more from the land than they require or the land can sustainably offer; that a balance of life must be maintained; that maintaining the wellbeing of their place in turn promotes their own wellbeing. Like other animals, humans who practiced low-intensity niche-engineering generally enriched their local ecosystems, rather than diminished them in the long term. For thousands of generations, humans lived within the natural limits of the world, shaping it and being shaped by it, like any other creature. Our numbers across the globe were slowly growing, but for ages our consumption and destruction did not overwhelm the biosphere.

Timing and Tumors

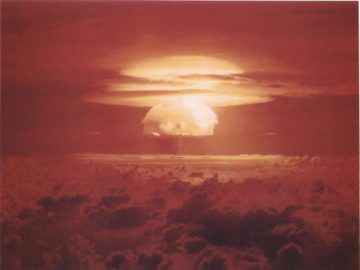

Given that we humans have been substantially influencing our environments for such a very long time, there’s much debate about when we really entered a time we can call the Anthropocene, which denotes the point at which human activity becomes the dominant force shaping the planet, altering it in ways that will leave measurable traces across millennia. Some would argue that the Anthropocene must begin with the human use of fire to affect the growth of forests and grasslands, at least a million years ago. Or it might begin with the spread of modern humans across the globe, which precipitated a megafaunal mass extinction, dead-ending a variety of animals who might (or might not) have evolved into new forms, when they were challenged by the end of the last glaciation and the warming into the Holocene. Or maybe it should start with the earliest domestication of plants and animals, which altered the future trajectory of many species and landscapes. Others argue that it should begin with fixed-field agriculture and the rise of city-states, such as those which arose in the Fertile Crescent during the mid-Holocene; at this time, the rate of species extinction picked up pace and carbon dioxide began to accumulate in the atmosphere to the point that it likely played a part in stabilizing the Holocene climate. But geologists, who are tasked with declaring a formal definition, seem partial to the 1950s, when the Western powers were zealously testing nuclear devices, blanketing the Earth in a thin film of radiation that will persist as a line in the soil strata and the remains of living things for millennia to come. At this same time, the fossil record also begins to change, showing far fewer non-human animals, in kind and in total, and far more human animals, as well as sudden and profound changes to the skeletons of certain species, like chickens and dogs and cattle, under the escalating force of artificial selection. Prodigious masses of concrete and newly invented plastic begin to accumulate on the surface of the planet. Mountainous quantities of lead, iron, copper, gold, and other metals are stripped from Earth’s interior and deposited upon its exterior. And the atmosphere is rapidly flooded with hundreds of millions of gigatons of carbon that had previously been locked away in the bowels of the Earth for hundreds of millions of years. Some call these developments the Great Acceleration, which rings similar to the Great Oxygenation Event.

Given that we humans have been substantially influencing our environments for such a very long time, there’s much debate about when we really entered a time we can call the Anthropocene, which denotes the point at which human activity becomes the dominant force shaping the planet, altering it in ways that will leave measurable traces across millennia. Some would argue that the Anthropocene must begin with the human use of fire to affect the growth of forests and grasslands, at least a million years ago. Or it might begin with the spread of modern humans across the globe, which precipitated a megafaunal mass extinction, dead-ending a variety of animals who might (or might not) have evolved into new forms, when they were challenged by the end of the last glaciation and the warming into the Holocene. Or maybe it should start with the earliest domestication of plants and animals, which altered the future trajectory of many species and landscapes. Others argue that it should begin with fixed-field agriculture and the rise of city-states, such as those which arose in the Fertile Crescent during the mid-Holocene; at this time, the rate of species extinction picked up pace and carbon dioxide began to accumulate in the atmosphere to the point that it likely played a part in stabilizing the Holocene climate. But geologists, who are tasked with declaring a formal definition, seem partial to the 1950s, when the Western powers were zealously testing nuclear devices, blanketing the Earth in a thin film of radiation that will persist as a line in the soil strata and the remains of living things for millennia to come. At this same time, the fossil record also begins to change, showing far fewer non-human animals, in kind and in total, and far more human animals, as well as sudden and profound changes to the skeletons of certain species, like chickens and dogs and cattle, under the escalating force of artificial selection. Prodigious masses of concrete and newly invented plastic begin to accumulate on the surface of the planet. Mountainous quantities of lead, iron, copper, gold, and other metals are stripped from Earth’s interior and deposited upon its exterior. And the atmosphere is rapidly flooded with hundreds of millions of gigatons of carbon that had previously been locked away in the bowels of the Earth for hundreds of millions of years. Some call these developments the Great Acceleration, which rings similar to the Great Oxygenation Event.

Whatever the geologists decide about the formal definition, it is useful to think about the start of the Anthropocene. It is useful to focus a question on what so fundamentally changed in human behavior that we went from being just one creature among many, to a becoming a dangerous entity on a scale unlike any other life form in billions of years, drastically upsetting the balance of life on our planet with such force that it’s crashing the biosphere. When did our species cross that threshold? If we can understand what changed in our ways of being, then we might be able to figure out what can be set right and how we might restore human societies to their useful place within the living world. Returning to the popular metaphor of humans as a cancer, what if we instead liken the human community to an organ that—just like every other community of life—plays a part in the regulation of the Earth as an organism, imagined as Gaia? It might then be fair to say that something in our tissues, or social fabric, has become diseased. This is to say human beings are not a disease; rather, human societies are infected by disease. If that metaphor holds, then our societies can also be restored to health. With proper diagnosis and treatment, why couldn’t we return to our salutary functioning in Earth’s web of life?

Readers of this series will know that I’ve come to think the present disease was caused by an idea—a meme, if you prefer—contracted by societies in the Fertile Crescent during the early to mid-Holocene, an idea that humans are essentially different from all other living creatures and are entitled to destroy or co-opt other lives without regard in the service of human paramountcy. Early Mesopotamian societies at least provide the first textual evidence in which people were beginning to compare themselves favorably with their gods, to imagine themselves as supra-Natural beings, entitled to possess and dominate what would increasingly come to be identified as Nature, separate from humanity. Once on this path, ordinary human greed and lust for power—with their own propulsive logic and rationalization—found new purchase, so that individuals and societies began to take more than they needed and to maintain a hierarchy through which they could dominate other people, animals, plants, and ecosystems in a manner and to a degree that had never before been done. Rather than being mindful of natural cycles and seasons for all living communities, respecting the web of life, the earliest agriculturalists began trying to separate their lands, their plants, and their animals from Nature’s web to build a human-centric one. In so doing, they obstructed the wellbeing of most of the people and animals under their control and also undertook to destroy those communities of living things that they did not favor. As they adopted increasingly chauvinistic values that vaunted their own domination over co-existence with other forms of living things and in discordance with the terms of biospheric integrity, they advanced their own growth. Their ideas spread, by force and by numbers, across the planet, until nearly all of us are overtaken by it, infected with it. When fossil fuels entered the veins of this uncontrolled overgrowth, it had the effect of a poison that favored the disease over healthy tissue—an inverse chemo-therapy. Fossil fuels have enabled the rise of technological innovations of the last century that—while amazing, creative, and transformational in so many ways—have further fueled the delusion that there are no ecological limits to salutary growth, that we can outpace all challenges through technological wizardry. The transient wealth fossil fuels have produced has buffered us from the long-term consequences of our ecological impact, thereby enabling extreme ecological overshoot. And the material excess they’ve helped to create has effectively normalized a disastrous, consumption-led, aspirational lifestyle around the world.

It seems increasingly clear that curing the condition requires us not only to leave fossil fuels in the ground, but also to expunge the corrupting meme, in all its variants of concern. But what is the healthy way to do this? What systems do we share, as humans, that enable us to ward off our grave cultural sickness? Maybe there are none. Maybe I just don’t know where to look. Maybe these are the wrong questions. But even if our predicament is caused by more than the suspicious Mesopotamian meme, finding the primary causes of the shift in our relationship with the rest of the biosphere seems integral to finding the cure to our civilizational ills—to discovering the antidote, which can restore health to the human presence in our world. Fortunately, there are those who are actively attempting to rediscover the principles of sustainable human societies.

Earlier Essays in this Series

1 What We Talk About When We Talk About The Weather

10 On Progress As Human Destiny

11 Of Gods And Men And Human Destiny

Images

1. The landscape of southeastern Idaho, near Pocatello. The land around the street where I grew up was quite similar. 75centralphotography

2. A rock showing bands of oxidized iron that were formed as it precipitated from the ocean during the Great Oxygenation Event, during the Precambrian Age. Photo by Graeme Churchard. Creative Commons.

3. Painting of Australian Aboriginal people burning grassland to hunt kangaroos in New South Wales. Painted by Joseph Lycett, 1817. National Library of Australia.

4. The mushroom cloud formed during a nuclear test on Bikini Atoll in 1954. Public Domain.