by Brooks Riley

Though we are an aggregator blog (providing links to content elsewhere) on all other days, on Mondays we have only original writing by our editors and guest columnists. Each of us writes on any subject we wish, and the length of articles generally varies between 1000 and 2500 words. Our writers are free to express their own opinions and we do not censor them in any way. Sometimes we agree with them and sometimes we don’t.Below you will find links to all our past Monday columns, in alphabetical order by last name of the author. Within each columnist’s listing, the entries are mostly in reverse-chronological order (most recent first).

by Brooks Riley

by Tim Sommers

“Cleave,” “buckle,” and “dust” are contranyms. They are their own opposites. To dust means to remove, or sprinkle, with dust. To buckle means to collapse or secure. To cleave means both to divide and to stick to tenaciously.

In that spirit, an astro-turf Federalist Society group, opposing affirmative action and pro-active diversity in college admissions, calls itself “Students for Fair Admissions.” The Supreme Court is on the brink of using two upcoming cases brought by Students for Fair Admissions – SFA v Harvard and SFA v the University of North Carolina – to end the last vestiges of any attempts to address discrimination in the college admissions process.

One of the most widely-quoted slogans in Supreme Court history – right up there with ‘You shouldn’t shout fire in a crowded theatre’ and ‘I can’t define obscenity, but I know it when I see it’ – is “The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.”

This approach to equal protection and fair equality of opportunity suggests that the way to address racial discrimination is to not see race, to be, metaphorically at least, color-blind. This is called the “categorization” approach to jurisprudence about race and it echoes the ‘Don’t say gay’ law in DeSantis’ Florida. It’s the ‘Don’t say race’ approach. (Also, the ‘Don’t say sex,’ but here I’ll stick with race, though I would be happy to discuss sex and other protected categories in comments.) Can we solve racism by being blind to race? Well, can we end discrimination against people with mobility challenges by not seeing wheelchairs? Read more »

by Dwight Furrow

When we speak about identity, we usually have in mind the various social categories we occupy—gender categories, nationality, or racial categories being the most prominent. But none of these general characteristics really define us as individuals. Each of us falls into various categories but so does everyone else. To say I’m a straight white male puts me in a bucket with millions of others. To add my nationality and profession only narrows it down a bit.

When we speak about identity, we usually have in mind the various social categories we occupy—gender categories, nationality, or racial categories being the most prominent. But none of these general characteristics really define us as individuals. Each of us falls into various categories but so does everyone else. To say I’m a straight white male puts me in a bucket with millions of others. To add my nationality and profession only narrows it down a bit.

While all these factors contribute to one’s identity, they don’t reach what makes each of us a distinct individual. Why should that matter? It matters in part because we want to be treated as an individual not a type, but also because having an understanding of one’s distinctive identity might help us decide what kind of life to live. It might help us guide our self-formation by reinforcing decisions tailored to one’s very specific needs, values, and aspirations.

So what does constitute our distinctiveness as persons? We might try to answer this by thinking about cases in which one’s identity is missing—what is commonly called an identity crisis. In an identity crisis we question our purpose in life, what our role or place in society is, what values we ought to be committed to, or the meaning and significance of our activities. But having purpose, meaning, and a commitment to certain values doesn’t quite individuate us either. We share values, commitments, and meanings with many others. These all seem necessary to us as individuals but aren’t sufficient to explain what makes us the distinctive selves we are.

When confronted with such puzzles we might hope that philosophy could straighten us out. However, the results of philosophical inquiry into questions of personal identity are mixed, although I think in the end helpful. Read more »

by Paul Braterman

There are two possible attitudes towards Scripture. One is to regard it as the direct and infallible word of God. This leads to certain problems. The other one, equally compatible with devotion, is to regard it as the recorded writings of men (it almost always is men), however inspired, writing at a specific time and place and constrained by the knowledge and concerns of that time. This invites deeper study of what was at stake for the writers, the unravelling of different narrative strands and voices, and discussion of whatever message the Scriptures may have for our own times. I expect that most readers here will adopt the second approach, while those who adopt the first are not to be dissuaded by mere rational argument, so why am I even discussing it?

There are two possible attitudes towards Scripture. One is to regard it as the direct and infallible word of God. This leads to certain problems. The other one, equally compatible with devotion, is to regard it as the recorded writings of men (it almost always is men), however inspired, writing at a specific time and place and constrained by the knowledge and concerns of that time. This invites deeper study of what was at stake for the writers, the unravelling of different narrative strands and voices, and discussion of whatever message the Scriptures may have for our own times. I expect that most readers here will adopt the second approach, while those who adopt the first are not to be dissuaded by mere rational argument, so why am I even discussing it?

Because we need to expose the hypocrisy of those powerful false prophets who, while claiming to be guided exclusively by Scripture, systematically misapply, distort, and even completely misquote the sacred text. That exactly is what Answers in Genesis, like other creationist organisations, does in its online writings, and in its Creation Museum and Ark Encounter.

I have come across four specific areas that concern me (no doubt there are many others):

I have written here before about the lengths to which all the major creationists organisations will go, acting in concert, to downplay the significance of human-caused global warming. Here I want to draw attention to just one of their regular arguments, most recently presented as a refutation of Greta Thunberg’s compilation The Climate Book. Read more »

by Ethan Seavey

The extant Kin of the Colonizer are paralyzed but that doesn’t stop them from running their mouths. They yap and yell and are filled with angst and guilt. Their rage fuels something, but that rage is only easy to find when they are pinned up against that Last True American Colonialist. Otherwise they surround themselves with each other and in there it is hard to be mad.

They hop in a rental car and they cross fields of naked-armed trees talking about that mythical land that once existed, before this one had paved it over. How beautiful New York state must have once been, before there were cameras to capture it. They cross the border into Canada and talk borders, how wide and unmanageable, how purposefully desolate, how torturous to cross without a white face. Their white lips talk of white powers and their pink tongues get lost and meander in circles. They ask if Canada is any “better” than the US and they see parallels but such vast differences that the question asked in the first place is deemed irrelevant.

At Niagara Falls they are like everyone else. They watch the falls in mostly silence. They take pictures and selfies. They walk up the cement pathway slowly and turn around every few steps. Again they talk about how it used to be. A sacred site for hundreds of years before white settlers. Then, a spiritual experience for earlier white settlers. They talk about how it is now: a strip of skyscraping hotels towering high over the wonder, dwarfing its excellence in order to give a white man in a business suit a better view. They notice the cemented pathways and the bridges spanning and the boats crossing and the people crowding and the spirit fading or already gone. They find the road lined with ferris wheels and go-carts and haunted houses and kitschy white nostalgia. Read more »

by Mark Harvey

Opinion has caused more trouble on this little earth than plagues or earthquakes. —Voltaire (1694 – 1778)

About the only good thing that comes out of huge natural disasters is that it brings otherwise feuding and even warring countries together in humanitarian rescue efforts. Immediately after the recent earthquake in Turkey and Syria, rescue teams from all over the world amassed huge amounts of food, medicine, clothing, and rescue equipment, boarded airplanes and trucks and swarmed into the two heavily damaged countries to do some genuine, unadulterated good.

An 80-member world-class search and rescue team plus four search dogs with world-class noses from the UK hit the ground in Gaziantep, Turkey, barely two days after the quake. The team arrived with specialized seismic listening devices, concrete cutting equipment, and shoring materials. The crew is self-sufficient and brought its own food, water, shelter, communication, and sanitation gear.

An 80-member rescue team from China, also with four dogs, arrived in Turkey the same day as the UK team. The Chinese came with 20 tons of medical and communications equipment. Read more »

by Deanna Kreisel [Dr. Waffle Blog]

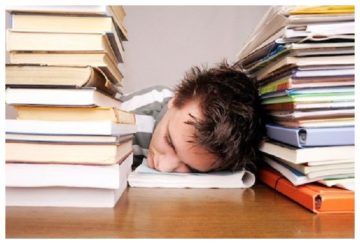

About a third of the way through a first-year humanities honors course, one of my more engaged and talkative students pulled me aside after class for a private chat. She waited, clearly anxious, while the rest of her classmates filed out and then turned to me with her eyes already filling up with tears.

About a third of the way through a first-year humanities honors course, one of my more engaged and talkative students pulled me aside after class for a private chat. She waited, clearly anxious, while the rest of her classmates filed out and then turned to me with her eyes already filling up with tears.

“I can’t read,” she said, her voice shaking.

I waited for her to elaborate, but nothing else was coming out. “Do you mean you’re having trouble finding time to do the assigned reading?” I ventured.

“No. I mean, yes, I am, but that’s not what I mean. I’m trying to read Pride and Prejudice,[1] I really am, but I don’t understand it.”

“Yes, well, as I’ve explained the language is antiquated and it takes some time to—”

“No, no!” she cried impatiently. “I know that. I mean I don’t know how to read a novel, a whole book. I can’t concentrate on it; my mind wanders. And then I can’t remember what happened, and I feel lost. It doesn’t make any sense to me. I just….can’t read,” she trailed off.

I clucked sympathetically as I tried to figure out what on earth to say.

“I’ve called my mom a bunch of times and cried on the phone to her. I am just so embarrassed. She said I should talk to you. Also, she suggested I listen to the audiobook. But I mean, is that cheating?”

I seized on the idea like a lifeline. “No, that would be fine,” I reassured her. “I suggest that you do both, though—listen to the audiobook as you’re following along with the text, so that you can eventually get better at comprehension.”

She was grateful; I gave her some tips on dealing with distractions and suggested she work with a tutor; she struggled through Jane Austen; tragedy and disaster were both averted. She got a little better at reading the assigned texts but continued to worry that it didn’t come naturally or easily to her.

This was an honors student. Read more »

“But in 2500 B.C. Harappa,

who cast in bronze a servant girl?

No one keeps records

of soldiers and slaves.”

… —from At the Museum, by Agha Shahid Ali

I’ve learned a new word:

asafoetida, or asafetida,

which is a gum ground from

Near Eastern plants of the genus Ferula

which smells fetid

…. and was used once as an antispasmodic,

two qualities which seem apropos

as news grinds down days from Gaza

to Homs to Aleppo

pulverizing both Us andThem

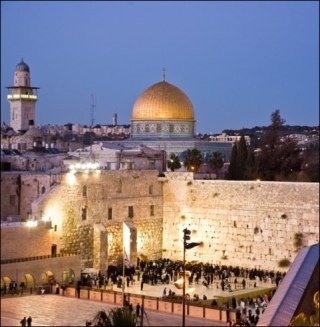

between a wall that wails

and a dome-sheltered rock

in Jerusalem which, by god,

is ever spastic and nothing

seems regretted

…. this new word came in a poem

of an Indian poet

who ran his pen across a page

to tell the fetid bitterness

found in bond of slave to lord,

bitterness cast in bronze in which,

by sculptor’s art, blood and pain

were vetted

Jim Culleny, ©5/23/18

____________________________

*The earliest mention of asafoetida in the historical record dates from the eighth century BC, when the plant was listed in an inventory of the gardens of Babylonian King Marduk-apla-iddina II. Not long after that, in Nineveh (near modern Mosul, Iraq), asafoetida was included in a catalogue of medicinal plants in the library of King Ashurbanipal.

by Andrea Scrima (excerpt from a work-in-progress)

My father, the son of Italian immigrants, was a member of the working class. There were things within reach, and things that were not in reach, and he accepted this. He never pushed his children to broaden their horizons, and would have been satisfied to see them in traditional working-class vocations. When I came home from school eager to show off my grades, he poked fun at me. The prospect of pursuing an intellectual career was alien to him; in his view, taking out student loans to go to college or university was a way for banks to trap the “little guy.” When I presented him with the papers, he refused to sign. There was no discussion. I eventually moved out and managed to get my BFA anyway, and when I wound up as a finalist for a Fulbright, the doctor who performed the general checkup required by the awarding commission—I was still covered by my father’s Blue Cross plan, but only because I was still technically a dependent and it didn’t cost him anything—took him aside and told him that a Fulbright would be “quite a feather in your daughter’s cap.”

My father, the son of Italian immigrants, was a member of the working class. There were things within reach, and things that were not in reach, and he accepted this. He never pushed his children to broaden their horizons, and would have been satisfied to see them in traditional working-class vocations. When I came home from school eager to show off my grades, he poked fun at me. The prospect of pursuing an intellectual career was alien to him; in his view, taking out student loans to go to college or university was a way for banks to trap the “little guy.” When I presented him with the papers, he refused to sign. There was no discussion. I eventually moved out and managed to get my BFA anyway, and when I wound up as a finalist for a Fulbright, the doctor who performed the general checkup required by the awarding commission—I was still covered by my father’s Blue Cross plan, but only because I was still technically a dependent and it didn’t cost him anything—took him aside and told him that a Fulbright would be “quite a feather in your daughter’s cap.”

He must have sensed something. My father mistrusted doctors, all of whom were crooks, and while he relayed the remark to me later, it didn’t seem to have made much of an impression on him. As it turned out, I didn’t receive the Fulbright; a short time later, when I won an equivalent scholarship from a German foundation to attend graduate school in Berlin, he threw me a skeptical look. To his mind, a stipend amounted to charity. It was like getting welfare, and because no self-respecting American would ever stoop so low, I was evidently on the wrong path. He’d already invented a new nickname for me when I moved out: “Wayward,” which neatly captured the moral deviance of a young woman leaving her parents’ home for any reason other than marriage. Yet for all his subtle mockery, I knew that he loved me and that I’d hurt him; now that I’d decided to strike it out on my own in a foreign country, I was leaving behind everything he’d ever known. Read more »

by David Greer

On the islands of the Salish Sea, spring is often interrupted by the final roars of winter’s lion. Firs and cedars that usually withstand storm winds from the west or south may break when a rare mass of Arctic air brings with it a mean gale from the north.

In a rural community, branches falling on wires can trigger power outages lasting hours or days. When that happens, the ancient woodstove takes over from the idled electric heat pump, while oil lamps brought out of the closet cast a warm and flickering light on the novel that has been waiting for just such an occasion. Sure, your iPhone may still have some juice left, but you’ve no idea whether the lights will be out for hours or days. What better excuse to bury yourself in a good book under a cozy woolen Hudson’s Bay blanket?

No power also means no water from the pump-driven dug well, but fortunately you had the presence of mind not to tear down the old outhouse from the cabin’s earliest days when indoor plumbing was a luxury enjoyed by few on these remote islands. As long as you remember to gently relocate any yellowjacket queens wintering under the toilet seat, there’s a certain pleasure to sitting in a privy overlooking the rainforest in the gloaming, the more so if you remembered to replace the empty toilet paper roll after the last power outage. On really stormy nights, you might even hear the waves crashing on the distant beach. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Just a Street Corner. Boston, 2022.

Sughra Raza. Just a Street Corner. Boston, 2022.

Digital photograph.

by Varun Gauri

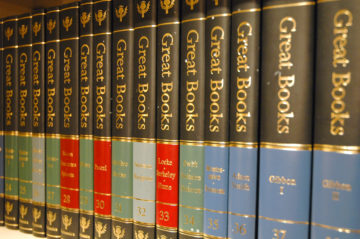

At the University of Chicago, I majored in an interdisciplinary concentration most easily characterized as Great Books. I studied with an Indian poet, a Japanese postmodern literary critic, and an historian who admired Michel Foucault, but my most influential professors were men influenced by Leo Strauss, including Allan Bloom, Joseph Cropsey, Leon Kass, and Nathan Tarcov, a smart and stirring group of teachers. They were also politically conservative, though I was too politically naive, and too flattered by their approval, to notice. Junior year, invited to speak about my selected Great Books at a humanities conference, I talked about the changing valence of cleverness in Homer, Aristotle, and Descartes. The conference took place in the context of the canon wars, and when during Q&A people asked me if there were women or non-European authors on my list, I offhandedly threw out a few names. A mentor would later compliment my disarming ingenuousness.

Some of the professors regretted their Eurocentrism but felt helpless to correct it, given their linguistic limitations. Others wore it proudly. Most notoriously, Saul Bellow supposedly said, “When the Zulus produce a Tolstoy, we will read him,” a position that Charles Taylor would take down in “The Politics of Recognition” (though, sadly, after I graduated). Even in the 1980s, though, many of us could tell there was something odd about the idea of a literary or philosophical canon in a multicultural society and long globalized world of letters. For what it was worth (and it wasn’t much, since canon expansion grows out of the same impulse as canon construction, tokenism in response to fetishism, still the scorekeeping), I made a point to include Hannah Arendt and The Mahabharata on my lists.

Looking back, I’m stunned not so much by the program’s male Eurocentrism, which was advertised (caveat emptor), but its insularity. Why did no one tell me about Becker’s Denial of Death, whose reinterpretation of psychoanalysis would have informed my essay on heroism? I read Nietzsche’s takedown of Christian morality but had no idea that Dewey had developed a more American and optimistic response to the death of God. I wish I’d known about Charles Taylor’s work on moral horizons, Margaret Atwood’s world-building, Tagore’s cosmopolitanism. The Great Conversation, it turns out, is much wider than I knew. It is, in fact, still going on. I might even have been a participant, in my own way, not just an eavesdropper. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by David J. Lobina

In this misguided series of posts on large language models (LLMs) and cognitive science, I have tried to temper some of the wildest discussions that have steadily appeared about language models since the release of ChatGPT. I have done so by emphasising what LLMs are and do, and by suggesting that much of the reaction one sees in the popular press, but also in some of the scientific literature, has much to do with the projection of mental states and knowledge to what are effectively just computer programs; or to apply Daniel Dennett’s intentional stance to the general situation: when faced with written text that appears to be human-like, or even produced by humans, and thus possibly expressing some actual thoughts, we seem to approach the computer programs that output such prima facie cogent texts as if they were rational agents, even though, well, there is really nothing there!

Naturally enough, many of the pieces that keep coming out about LLMs remain, quite frankly, hysterical, if not delirious. When one reads about how a journalist from the New York Times freaked out when interacting with a LLM because the computer program behaved in the juvenile and conspiratorial manner that the model no doubt “learned” from some of the data it was fed during training, one really doesn’t know whether to laugh or cry (one is tempted to tell these people to get a grip; or as Luciano Leggio was once told…).[i]

More importantly, when people insist that LLMs have made passing the Turing Test boring and have met every challenge from cognitive science, and even that the models show that Artificial General Intelligence is already here (whatever that is; come back next month for my take), one must at least raise one eyebrow. Here’s a recent, fun interaction with ChatGPT, inspired by one Steven Pinker (DJ stands for you-know-who):

So, no, LLMs definitely don’t exhibit general intelligence, and they haven’t passed the Turing Test, at least if by the latter we mean partaking in a conversation as a normal person would, with all their cognitive quirks and what not. Read more »

by Mike Bendzela

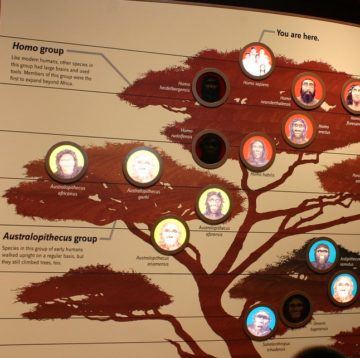

Narrative is the elucidation of backstory. Thus, narrative partakes of other stories, is composed of them. There is no infinite regress of narratives, though. At the end lies a cosmology, which I use here to mean a master story, or, “a doctrine describing the natural order of the universe.” This the ground of all narrative. Our stories must in some way enact a cosmology.

Until recently, cosmologies have not been based on empirical observation and evidence—because they couldn’t be. What did we know? How could we even know that we didn’t know? Instead, we relied on revelation and tradition. Such narratives deprived of a factual backstory may speculate about the causes of action, but such stories would be shams. When our backstory is wrong, our story is absurd, but we have had no way of knowing this—until now. Read more »

by Carol A Westbrook

I admit it. I am a breakfast skipper.

I’m not ashamed of it, and I don’t force myself to eat a morning meal just because it’s the societal norm. Sometimes, for the sake of sociability and good conversation, I’ll sit down to breakfast and pretend to nibble at a piece of dry toast, or push eggs around my plate. The fact is, I just don’t feel hungry at breakfast time.

About 10% of adults are like me. Their inherent biorhythms dictate that they are not hungry at breakfast time. I could never understand why the other 90% regard breakfast as the most important meal of the day, or why it is good for a person’s health to eat breakfast. The classical American breakfast of 2 eggs, bacon, and toast with butter and jam has almost 600 calories, 30 g of fat, and 1.4 g of salt! That’s hardly a nutritious start to the day. Fortunately, surveys have shown that most people prefer a bowl of cereal and milk, which has only about 250 calories.

In the US, most people eat breakfast before they begin their day, but that was not true for most of humanity through the ages. Although the ancient Greeks ate 3 meals each day, including a breakfast of bread soaked in wine at the very start of the day, early breakfasts did not continue through the Middle Ages. In the Middle Ages, the serfs started their day without food, since they were not allowed to eat before daily Mass. After Mass, they ate a large meal to supply the calories they would need for their upcoming manual labor. This meal was called the “break-fast meal” or just breakfast. Read more »

Transcribed by Rafiq Kathwari

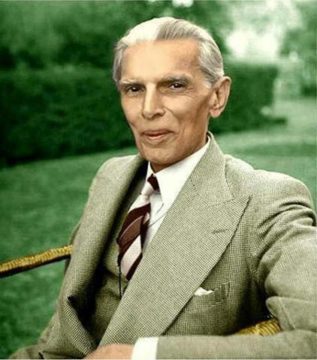

Mohammed Ali Jinnah’s Last Visit to Kashmir 10 May – 25 July 1944

Mohammed Ali Jinnah’s Last Visit to Kashmir 10 May – 25 July 1944

Tue 9 May 1944

Mr. Jinnah was to arrive today, but he had sent a telephone message last evening that as he was tired, he could not make the journey in one day. In the evening, there was a public meeting held at Amira Kadal. Sheikh Abdullah addressed the public and exhorted them to give a right royal reception tomorrow to Mr. Jinnah.

Wed 10 May 1944

Quite an excitement from morning about Mr. Jinnah’s arrival today at 1:30 p.m. Without lunch went with G.M. Bakshi to Qazi Gund to receive the Quaid-e-Azam there. Enroute everywhere people waiting to receive the Qaid-e-Azam: at Khanabal, a large gathering. Had a little meal at Qazi Gund.

Mr. Jinnah arrived at about 4 p.m. There was some disturbance as he reached quite abruptly, and he started off. With him in other cars were Chaudry Gulam Abbas, Maulvi Yusuf Shah, and others of that group. Read more »

by Paul Braterman

UPDATE (March 13, 2023, 8 AM): Gary Lineker has been reinstated, and has reaffirmed his position:

A final thought: however difficult the last few days have been, it simply doesn’t compare to having to flee your home from persecution or war to seek refuge in a land far away. It’s heartwarming to have seen the empathy towards their plight from so many of you.

The first part of Attenborough’s series was broadcast in BBC1 TV last night to general acclaim. There is no further word from the BBC as to why the last part will not be shown except on iPlayer.

The BBC is currently under pressure over its pro-Government bias, as a result of two separate episodes. One of these has drawn enormous publicity, while the other has been barely noticed outside a handful of the more serious newspapers. Yet I consider the latter to be the more serious by far, and not just because I consider the environment more important than football.

Let me start with an episode that has led former BBC Director General Greg Dyke to say that the BBC has undermined its own credibility because it will be viewed as having bowed to government pressure, while Roger Mosey, a former head of BBC TV News, has said that BBC chairman Richard Sharp has damaged the corporation’s credibility and should stand down. Mosey, incidentally, is now Master of Selwyn College, Cambridge, where the current Director General, Tim Davie, was an undergraduate – a reminder of the narrowness of the base from which the U.K.’s ruling classes draw their talent. Read more »