by Brooks Riley

Though we are an aggregator blog (providing links to content elsewhere) on all other days, on Mondays we have only original writing by our editors and guest columnists. Each of us writes on any subject we wish, and the length of articles generally varies between 1000 and 2500 words. Our writers are free to express their own opinions and we do not censor them in any way. Sometimes we agree with them and sometimes we don’t.Below you will find links to all our past Monday columns, in alphabetical order by last name of the author. Within each columnist’s listing, the entries are mostly in reverse-chronological order (most recent first).

by Brooks Riley

by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

I was nineteen when I first saw Venice. My college boyfriend and I had taken an overnight train from Vienna and arrived in the mist of early morning. It was late summer. This was at the tail end of almost three months in India, where I saw my fill of glorious wonders. Still, nothing could have prepared me for my first glimpse of the fabled city. First of all, I hadn’t expected the Grand Canal to be right outside the train station. Boarding a vaporetto, I sat speechless. The canal was shimmering like a vision from a dream. Church bells could be heard just above the loud din of the boats, and everywhere I looked: marble palaces stood crumbling into the water. I vividly remember my heart racing as I looked around, not believing the place was real.

“A wonder of the world,” my boyfriend called it on the train from Vienna.

And when I at last found my voice, I asked, “Why does anyone live anywhere else?”

He just laughed.

That was in 1990.

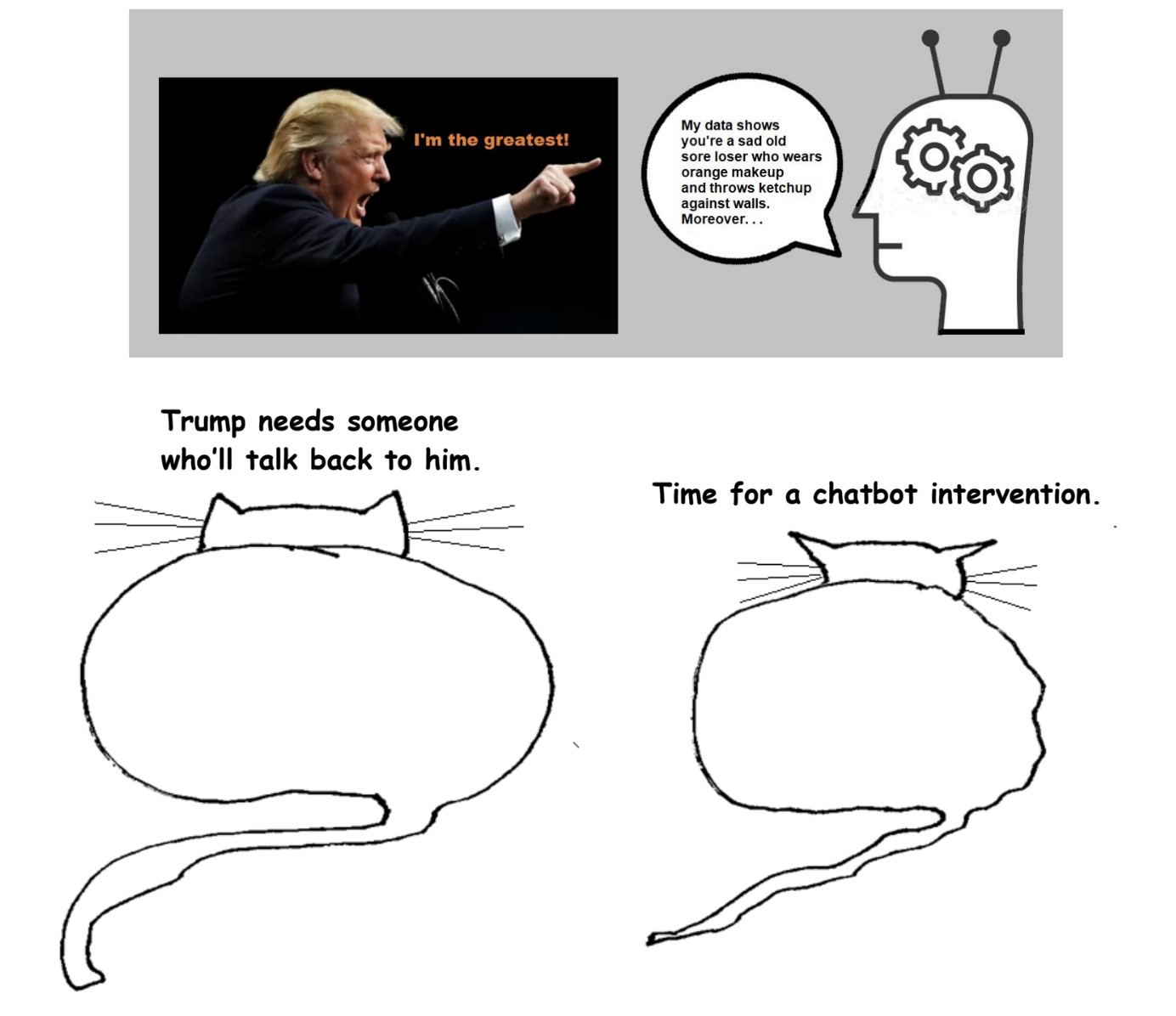

Then as now, traveling to Venice meant being able to view the work of the dazzling trio of Venetian artists that Henry James claimed would “form part of your life in Venice.” Giovanni Bellini and Tintoretto, as well as the great Carpaccio, said James “shall illuminate your view of the universe.” James was hinting at the way that these painters’ works exert an overwhelming power, not only over the way we see Venice, but over our vision of the world. And this is especially true when the great pictures are viewed in situ, in the palaces and churches for which they were originally created. Read more »

by Rafaël Newman

My favorite bookstore closed this month. Well, my favorite bookstore in Zurich, where I live. Also it hasn’t actually closed, it’s only changing hands. But Pile of Books, opened in 2007 by Daniel Nufer and run by him and his wife, Verena Nufer-Huber, until two weeks ago, has been such an expression of Dani’s character that it is hard to imagine the form it will take in his absence.

My favorite bookstore closed this month. Well, my favorite bookstore in Zurich, where I live. Also it hasn’t actually closed, it’s only changing hands. But Pile of Books, opened in 2007 by Daniel Nufer and run by him and his wife, Verena Nufer-Huber, until two weeks ago, has been such an expression of Dani’s character that it is hard to imagine the form it will take in his absence.

There have been other bookstores in my life, of greater or lesser importance to me depending on my phase of development. There was for instance the gift shop on Saint Catherine Street, in Montreal, the city of my birth, where my grandparents took me in the mid-1970s to pick out a Passover present (actually my ransom for finding the afikomen), and I, in an early gesture of perversity, chose a glossy album commemorating the Tutankhamun exhibition. Then there was Britnell’s, at Yonge and Bloor in Toronto, the city in which I came of age following our move from Quebec in the wake of the Révolution tranquille—a shop now long gone but in the late 1970s an invitingly Dickensian emporium, and the site of my first agonized Christmas gift-buying with an embryonic disposable income. Later, after my departure from Canada, there was Micawber Books, the explicitly Dickensian shop in Nassau Street, in Princeton, New Jersey, where I had my copy of Time’s Arrow signed by its author, Martin Amis, who was in town to give a coruscating talk on American socio-politics and to reminisce about his childhood on campus when his father lectured at Princeton in the 1950s. Read more »

I became hooked on Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan” in the Spring of 1969, my last semester as an undergraduate at Johns Hopkins. Three years later “Kubla Khan” had become the standard against which I measured my understanding of the human mind. That is why I am about to tell a story about how my interest in the mind has evolved through “Kubla Khan” to include, most recently, ChatGPT. Strange as it may seem, that poem is the vehicle through which I am coming to terms with this new technology and arriving at a sense of its potential.

There is a sense in which the story of that great poem can be traced back to the 11th century invasion of Britain by the Norman French, for that’s what gave rise to the English language. Some centuries later that story encountered a tale born of an encounter between an Italian merchant, Marco Polo, and a Mongolian warlord, Kubla Khan, which, when enlivened by the East India Company’s trade in opium, set fire to the mind of Samuel Taylor Coleridge in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. We need not trace that trajectory in any detail. I mention it only to give a sense of the scope of this 54-line poem, which is one of the best-known poems in the English language, and is perhaps unique in the annals of Western literature. It has made its mark on popular culture, from Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane, where it names Kane’s estate, Xanadu, thereby establishing the matrix for the whole film, to a hit song and film by Olivia Newton-John, Xanadu, and even provided that most vulgar of real-estate barons, Donald Trump, with the name for the nightclub, Xanadu, in his now defunct Atlantic City casino. Read more »

by Bill Murray

Zambia is home to a near-blind species of Ansell’s mole-rats that can sense magnetic fields with their eyes. It is part home to the world’s largest artificial lake by volume, and home to the world’s largest curtain of falling water. But that’s not why I want to go to Zambia. I want to go to Zambia because it is at the far end of an eighteen hundred kilometer railway halfway across the middle of Africa called the Mukuba Express, leaving every Friday from Dar es Salaam.

Neither a luxury Rovos Rail-type train for well-heeled retirees, nor a people-on-top desperation ride, the Mukuba Express is what I understand to be an ordinary, working means of transport African style, chugging across the Tanzanian plain from the coast and into the Zambian hills, offering third, second and first classes, restaurant cars between classes and a bar car.

If similar experience holds, the Mukuba Express will set out across the savannah triumphant and hopeful, restaurants and lounge bursting with goodwill and chilled beverages. The goodwill will remain as the cold boxes lose their vigor, their contents seeking room temperature. This has yet to be seen and will be reported further, but I believe it to be likely true.

This is a Tazara train, “ta” as in Tanzania, “za” as in Zambia “ra” as in railway, run by the Tanzania-Zambia Railway authority. The express route approaches 42 hours if the trains run on time, which they do not. The ordinary service “stops at every serviceable railway station in the respective regions of Tanzania and Zambia” and takes about two days. Read more »

by Marie Snyder

The season finale of The Last of Us sets up a great deontological v. teleological conundrum with the big question (tiny spoiler), which ends up being an episode-long trolley problem: Is it right to kill one person if doing so could save multitudes?

The season finale of The Last of Us sets up a great deontological v. teleological conundrum with the big question (tiny spoiler), which ends up being an episode-long trolley problem: Is it right to kill one person if doing so could save multitudes?

In a utilitarian view, of course we should sacrifice one person to potentially save all of humanity. It would be absurd not to see this and ensure the safety of all! But it doesn’t pass the categorical imperative sniff test. We can’t support intentional harm coming to people, any people, no matter how few, even if it will help many others.

Kant’s famous rule: “I am never to act otherwise than so that I could also will that my maxim should become a universal law,“ so killing a person to help others is necessarily wrong. It’s not a numbers game since “the moral worth of an action does not lie in the effect expected.” And we have to treat each person as an end in themselves, never as a means to an end.

Or, as the great Mitchell & Webb make clear, killing some to save others is just plain wrong “because it’s offensive and evil.”

And people will do absolutely anything to save the children they love if they turn out to be the sacrificial lambs in question.

Fortunately, the current issues facing us don’t force us to choose. We can help our children and the world at once, so that should be easy, right?!? Unfortunately, our drive to protect our kids is often short sighted. Life is not as cut and dried as a good zombie-like show. We often want our children to be happy today even if it means they end up suffering later. Read more »

by Ashutosh Jogalekar

Two weeks ago, outside a coffee shop near Los Angeles, I discovered a beautiful creature, a moth. It was lying still on the pavement and I was afraid someone might trample on it, so I gently picked it up and carried it to a clump of garden plants on the side. Before that I showed it to my 2-year-old daughter who let it walk slowly over her arm. The moth was brown and huge, almost about the size of my hand. It had the feathery antennae typical of a moth and two black eyes on the ends of its wings. It moved slowly and gradually disappeared into the protective shadow of the plants when I put it down.

Two weeks ago, outside a coffee shop near Los Angeles, I discovered a beautiful creature, a moth. It was lying still on the pavement and I was afraid someone might trample on it, so I gently picked it up and carried it to a clump of garden plants on the side. Before that I showed it to my 2-year-old daughter who let it walk slowly over her arm. The moth was brown and huge, almost about the size of my hand. It had the feathery antennae typical of a moth and two black eyes on the ends of its wings. It moved slowly and gradually disappeared into the protective shadow of the plants when I put it down.

Later I looked up the species on the Internet and found that it was a male Ceanothus silk moth, very prevalent in the Western United States. I found out that the reason it’s not seen very often is because the males live only for about a week or two after they take flight. During that time they don’t eat; their only purpose is to mate and die. When I read about it I realized that I had held in my hand a thing of indescribable beauty, indescribable precisely because of the briefness of its life. Then I realized that our lives are perhaps not all that long compared to the Ceanothus moth’s. Assuming that an average human lives for about 80 years, the moth’s lifespan is about 2000 times shorter than ours. But our lifespans are much shorter than those of redwood trees. Might not we appear the same way to redwood trees the way Ceanoth moths or ants appear to us, brief specks of life fluttering for an instant and then disappearing? The difference, as far as we know, is that unlike redwood trees we can consciously understand this impermanence. Our lives are no less beautiful because on a relative scale of events they are no less brief. They are brief instants between the lives of redwood trees just like redwood trees’ lives are brief instants in the intervals between the lives of stars.

I have been thinking about change recently, perhaps because it’s the standard thing to do for someone in their forties. But as a chemist I have thought about change a great deal in my career. The gist of a chemist’s work deals with the structure of molecules and their transformations into each other. The molecules can be natural or synthetic. They can be as varied as DNA, nylon, chlorophyll, rocket fuel, cement and aspirin. But what connects all of them is change. At some point in time they did not exist and came about through the union of atoms of carbon, oxygen, hydrogen, phosphorus and other elements. At some point they will cease to be and those atoms will become part of some other molecule or some other life form. Read more »

by Steven Gimbel and Gwydion Suilebhan

Philosopher Harry Frankfurt is best known for his article-turned-manuscript On Bullshit, in which he distinguishes between lying and bullshitting. Most of us are raised to condemn liars more than bullshit artists, but Frankfurt makes the claim that we’ve all got it backwards. His argument is philosophical, rather than scientific, which means observable evidence is hard to come by, but recent political events have filled the gap.

Philosopher Harry Frankfurt is best known for his article-turned-manuscript On Bullshit, in which he distinguishes between lying and bullshitting. Most of us are raised to condemn liars more than bullshit artists, but Frankfurt makes the claim that we’ve all got it backwards. His argument is philosophical, rather than scientific, which means observable evidence is hard to come by, but recent political events have filled the gap.

Fox News commentator Tucker Carlson regularly makes the news as a provocateur, but during the last couple of weeks, he has found himself IN the news. A major mouthpiece supporting Donald Trump before, during, and after his presidency, Carlson sent problematic text messages that became public during the libel case initiated by Dominion Voting Systems. Stories about his texts have dominated a few news cycles.

Carlson’s texts were problematic for two reasons. First, Carlson had been one of the primary voices pushing “the big lie” that the election of Joe Biden was the result of fraud. His texts revealed that Carlson knew the lie was a lie, even as he claimed it wasn’t on air. He was intentionally seeking to undermine a free and fair election in order to play a part in a conspiracy designed to install an unelected leader in the White House.

Second, Carlson’s texts revealed that while he was lying on air in support of Trump’s attempt to subvert democracy, he was secretly telling confidants he hated Trump passionately and thought he was a poor President. “That’s the last four years,” he wrote. “We’re all pretending we’ve got a lot to show for it, because admitting what a disaster it’s been is too tough to digest. But come on. There isn’t really an upside to Trump.”

Because of Carlson’s role as a leading Trump apologist, House Speaker Kevn McCarthy gave him exclusive access to thousands of hours of video of the January 6th insurrection. Carlson used that access to create a propaganda report, cherry-picking calm moments from the insurrection to mislead viewers about what actually happened on January 6th. His effort to soft-pedal the attack was so extreme that even Republican senators condemned it. Kevin Kramer from North Dakota called Carlson’s piece a lie, but North Carolina’s Thom Tillis called it bullshit. Which was it, though, really? Read more »

Here’s an idea:

in FB scroll down at say

a post a second —keep on keeping on

(maybe Meta’s your thing)

find your groove, lose yourself

in avatars and memes,

get a timely sense of your milieu,

what you’re enmeshed in now, good or ill,

a scroll of streaming truth, or not, soundless,

unless you hum a track yourself; but not downbeat,

keep it up and light or you’ll fly off rails

it might be meditative,

but whateva,

considering the stakes,

there must be something betta

than Meta

Jim Culleny, © 5/26/16

by Chris Horner

Less disappointing than life, great works of art do not begin by giving us all their best. —Proust

…for here there is no place

that does not see you. You must change your life. —Rilke

Everything demands our attention. A ceaseless stream of electronic information and entertainment flows through and around us. Attention spans shrink, and we struggle to focus on anything for more than a few minutes. Entertainment waits on every click, as does ennui. Paradoxically, we may come to want the things that we cannot have in an instant, that demand our time and patience before they will reveal all they have to offer: the art that demands that we slow down. To really appreciate those productions of culture that can refresh us, make us think, immerse us in beauty, even strike us with terror, takes time. Art that is challenging often requires this of us. This can be true of more ‘popular’ art forms too, if they have the kinds of layers that take time to be appreciated. Their advantage over what I’m calling ‘slow art’ is they give us an immediate sugar rush that keeps our attention on them (exciting narrative, easy to recall musical ‘hook’ etc) and which encourage us to return to them again and again. There’s nothing wrong with that. But not all art will do that, or not as often and as easily. Slow art, if it is great art, demands our time and patience before it will reveal all it has and can be to us. We should welcome this, for not only does this art often reward us most for our patience, but the practice of paying attention is itself, understood rightly, a kind of joy. There is an art that can offer us a world if we will but attend. Read more »

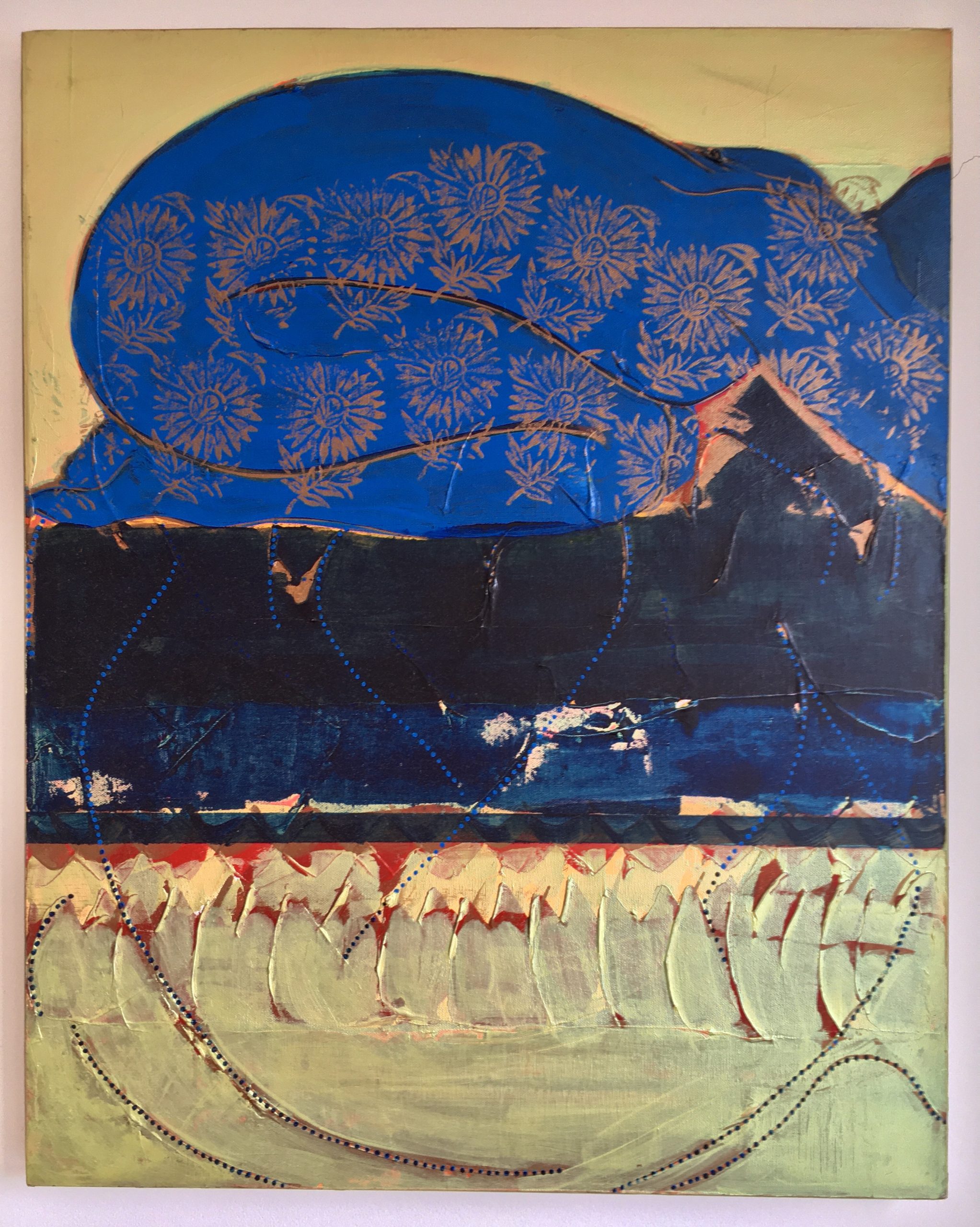

Sughra Raza. Untitled. Cambridge, 1999-2000.

Sughra Raza. Untitled. Cambridge, 1999-2000.

Acrylic on canvas.

by Claire Chambers

Having begun Hindi and eventually reaching an intermediate level, I sailed into the vast ocean of the Urdu language. There, a novice again, I felt lost amid roiling currents. Yet I kept my compass pointed towards receptivity, hoping the winds of curiosity would steer me to the shores of understanding. I’m not there yet, so join me in my voyage.

Having begun Hindi and eventually reaching an intermediate level, I sailed into the vast ocean of the Urdu language. There, a novice again, I felt lost amid roiling currents. Yet I kept my compass pointed towards receptivity, hoping the winds of curiosity would steer me to the shores of understanding. I’m not there yet, so join me in my voyage.

As Liz Chatterjee wryly notes, ‘It is obligatory to point out that Urdu is a cognate of “horde” and its name came from the Muslim occupiers’ ordu, camp’. This is because the language developed among the armies of the Delhi Sultanate and the Mughal Empire, whose soldiers used a mixture of Indian languages and Persian as a lingua franca. Over time, this melange of languages came to be known as Urdu, and the Perso-Arabic script was used to write it.

Leaping forward a century or two, the Partition of 1947 was a traumatic event that left many Urdu-speaking people feeling alienated and excluded from the new Indian society. Partition has caused a shift in the perception of Urdu, which has been reduced to a language spoken primarily by the elderly and by Muslim minorities in India. After Partition, Urdu became the national language of Pakistan, while Hindi was India’s official language (soon joined by English). Despite this, Urdu continued to be spoken by millions of people in India, and it is still one of the 22 scheduled languages of India. In the decades following Partition, however, the use of Urdu in India declined due to a variety of political, social, and economic factors. Many people who spoke Urdu as their first language began to switch to Hindi, and the use of Urdu in education, films, and government business also languished. Today, Urdu remains an important language in India, but it is not as widely spoken as it once was. Read more »

by Eric Bies

On the night of July 13, 1977, the old god Zeus roused from his slumber with a scratchy throat. Reaching drowsily for the glass by his bedside, his arm knocked a handful of thunderbolts from the nightstand. Swift and white, they rattled across the floor to the mountain’s, his home’s, precipitous edge: off they rolled and dropped to plummet through the dark. That night, great projectiles of angular light splashed against and extinguished New York City’s billion fluorescent eyes.

On the night of July 13, 1977, the old god Zeus roused from his slumber with a scratchy throat. Reaching drowsily for the glass by his bedside, his arm knocked a handful of thunderbolts from the nightstand. Swift and white, they rattled across the floor to the mountain’s, his home’s, precipitous edge: off they rolled and dropped to plummet through the dark. That night, great projectiles of angular light splashed against and extinguished New York City’s billion fluorescent eyes.

A week later, John Gardner turned 44—a fortuitous number, for the American novelist and medievalist was on a roll. That year alone he was set to see the publication of two children’s books, a collection of short stories, a work of criticism, and a biography. Six years had passed since the release of a short novel, Grendel, his ingenious Frankenstein-ing of the Beowulf myth that is read in American high schools to this day. Eleven years later, at the age of 49, Fate would see fit to fling him from his motorcycle and strike him dead. But first, in 1977, he had to publish his Life and Times of Chaucer. Owing to novelistic tendencies, the work has probably received more admiration from laymen than academics (rather redemptive as far as literary legacies go, actually). It is one of those books, unhampered by its erudition, that is a joy to read all the way through to the bitter end, and its final paragraph, as Steve Donoghue has pointed out, remains one of the strangest, strongest, and most memorable deathbed scenes in our literature:

When he finished he handed the quill to Lewis. He could see the boy’s features clearly now, could see everything clearly, his “whole soul in his eyes”—another line out of some old poem, he thought sadly, and then, ironically, more sadly yet, “Farewell my bok and my devocioun!” Then in panic he realized, but only for an instant, that he was dead, falling violently toward Christ.

The “bok” to which Chaucer says his goodbye is, of course, The Canterbury Tales. Had he had the time, Chaucer would have gladly doubled the length of his book. Who knows what he must have truly felt to take leave of his Knight, his Miller, his Pardoner, his Monk? Readers of this magnificent story cycle will readily sympathize. For even a writer as self-assured as Chaucer could not have anticipated how well and how dearly his countrymen would come to know his characters. The fact that the book remained unfinished at the time of his death did practically nothing to impede its momentous rise. Thankfully, just sixteen years after Chaucer fell violently toward Christ, England got its Gutenberg. When William Caxton set up press in Westminster, the first pages he printed were wet with the ink of Chaucer’s quill. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Tim Sommers

“Cleave,” “buckle,” and “dust” are contranyms. They are their own opposites. To dust means to remove, or sprinkle, with dust. To buckle means to collapse or secure. To cleave means both to divide and to stick to tenaciously.

In that spirit, an astro-turf Federalist Society group, opposing affirmative action and pro-active diversity in college admissions, calls itself “Students for Fair Admissions.” The Supreme Court is on the brink of using two upcoming cases brought by Students for Fair Admissions – SFA v Harvard and SFA v the University of North Carolina – to end the last vestiges of any attempts to address discrimination in the college admissions process.

One of the most widely-quoted slogans in Supreme Court history – right up there with ‘You shouldn’t shout fire in a crowded theatre’ and ‘I can’t define obscenity, but I know it when I see it’ – is “The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.”

This approach to equal protection and fair equality of opportunity suggests that the way to address racial discrimination is to not see race, to be, metaphorically at least, color-blind. This is called the “categorization” approach to jurisprudence about race and it echoes the ‘Don’t say gay’ law in DeSantis’ Florida. It’s the ‘Don’t say race’ approach. (Also, the ‘Don’t say sex,’ but here I’ll stick with race, though I would be happy to discuss sex and other protected categories in comments.) Can we solve racism by being blind to race? Well, can we end discrimination against people with mobility challenges by not seeing wheelchairs? Read more »

by Dwight Furrow

When we speak about identity, we usually have in mind the various social categories we occupy—gender categories, nationality, or racial categories being the most prominent. But none of these general characteristics really define us as individuals. Each of us falls into various categories but so does everyone else. To say I’m a straight white male puts me in a bucket with millions of others. To add my nationality and profession only narrows it down a bit.

When we speak about identity, we usually have in mind the various social categories we occupy—gender categories, nationality, or racial categories being the most prominent. But none of these general characteristics really define us as individuals. Each of us falls into various categories but so does everyone else. To say I’m a straight white male puts me in a bucket with millions of others. To add my nationality and profession only narrows it down a bit.

While all these factors contribute to one’s identity, they don’t reach what makes each of us a distinct individual. Why should that matter? It matters in part because we want to be treated as an individual not a type, but also because having an understanding of one’s distinctive identity might help us decide what kind of life to live. It might help us guide our self-formation by reinforcing decisions tailored to one’s very specific needs, values, and aspirations.

So what does constitute our distinctiveness as persons? We might try to answer this by thinking about cases in which one’s identity is missing—what is commonly called an identity crisis. In an identity crisis we question our purpose in life, what our role or place in society is, what values we ought to be committed to, or the meaning and significance of our activities. But having purpose, meaning, and a commitment to certain values doesn’t quite individuate us either. We share values, commitments, and meanings with many others. These all seem necessary to us as individuals but aren’t sufficient to explain what makes us the distinctive selves we are.

When confronted with such puzzles we might hope that philosophy could straighten us out. However, the results of philosophical inquiry into questions of personal identity are mixed, although I think in the end helpful. Read more »

by Paul Braterman

There are two possible attitudes towards Scripture. One is to regard it as the direct and infallible word of God. This leads to certain problems. The other one, equally compatible with devotion, is to regard it as the recorded writings of men (it almost always is men), however inspired, writing at a specific time and place and constrained by the knowledge and concerns of that time. This invites deeper study of what was at stake for the writers, the unravelling of different narrative strands and voices, and discussion of whatever message the Scriptures may have for our own times. I expect that most readers here will adopt the second approach, while those who adopt the first are not to be dissuaded by mere rational argument, so why am I even discussing it?

There are two possible attitudes towards Scripture. One is to regard it as the direct and infallible word of God. This leads to certain problems. The other one, equally compatible with devotion, is to regard it as the recorded writings of men (it almost always is men), however inspired, writing at a specific time and place and constrained by the knowledge and concerns of that time. This invites deeper study of what was at stake for the writers, the unravelling of different narrative strands and voices, and discussion of whatever message the Scriptures may have for our own times. I expect that most readers here will adopt the second approach, while those who adopt the first are not to be dissuaded by mere rational argument, so why am I even discussing it?

Because we need to expose the hypocrisy of those powerful false prophets who, while claiming to be guided exclusively by Scripture, systematically misapply, distort, and even completely misquote the sacred text. That exactly is what Answers in Genesis, like other creationist organisations, does in its online writings, and in its Creation Museum and Ark Encounter.

I have come across four specific areas that concern me (no doubt there are many others):

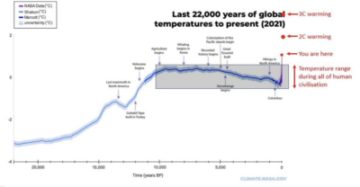

I have written here before about the lengths to which all the major creationists organisations will go, acting in concert, to downplay the significance of human-caused global warming. Here I want to draw attention to just one of their regular arguments, most recently presented as a refutation of Greta Thunberg’s compilation The Climate Book. Read more »

by Ethan Seavey

The extant Kin of the Colonizer are paralyzed but that doesn’t stop them from running their mouths. They yap and yell and are filled with angst and guilt. Their rage fuels something, but that rage is only easy to find when they are pinned up against that Last True American Colonialist. Otherwise they surround themselves with each other and in there it is hard to be mad.

They hop in a rental car and they cross fields of naked-armed trees talking about that mythical land that once existed, before this one had paved it over. How beautiful New York state must have once been, before there were cameras to capture it. They cross the border into Canada and talk borders, how wide and unmanageable, how purposefully desolate, how torturous to cross without a white face. Their white lips talk of white powers and their pink tongues get lost and meander in circles. They ask if Canada is any “better” than the US and they see parallels but such vast differences that the question asked in the first place is deemed irrelevant.

At Niagara Falls they are like everyone else. They watch the falls in mostly silence. They take pictures and selfies. They walk up the cement pathway slowly and turn around every few steps. Again they talk about how it used to be. A sacred site for hundreds of years before white settlers. Then, a spiritual experience for earlier white settlers. They talk about how it is now: a strip of skyscraping hotels towering high over the wonder, dwarfing its excellence in order to give a white man in a business suit a better view. They notice the cemented pathways and the bridges spanning and the boats crossing and the people crowding and the spirit fading or already gone. They find the road lined with ferris wheels and go-carts and haunted houses and kitschy white nostalgia. Read more »