by Kyle Munkittrick

Silicon Valley has rediscovered ‘taste.’ Maybe it was Jony Ive at Stripe Sessions. Maybe it’s Substack aesthetes like Henry Oliver and David Hoang. Maybe it’s everyone trying to figure out if AI can have taste. But taste is, in every case, either ill or incorrectly defined, if at all. Let’s fix that.

Taste is the valuing of craft.

That is, taste is the ability to assess and appreciate a work based on deep understanding of techniques and skills used in the work’s creation, whether it’s a car, a novel, an app, a song, or an outfit.

In Jasmine Sun and Robin Sloan’s Utopia Debate “Can AI have taste?”, Sun argued that if the YouTube or Spotify algorithm ever gave you a good recommendation, then yes AI has taste, because it understood and recreated your taste.

No. Algorithms understand your preferences. Taste is not your preferences. Preferences are, however, the thing most commonly conflated with taste.

Your preferences are intuitive taste—a starting point. Preferences rarely ever fully match with taste. That is what a guilty pleasure is! You like it even though you know it’s not good (Stranger Things), or hate it even though it is (Hemingway). Paying close attention to what you like is an excellent way of building taste. Preferences are a great signal that something might be good.

The opening paragraph of Roger Ebert’s review of the Mummy is a perfect demonstration of his exceptional taste being in seeming conflict with his preferences:

There is within me an unslaked hunger for preposterous adventure movies. I resist the bad ones, but when a “Congo” or an “Anaconda” comes along, my heart leaps up and I cave in. “The Mummy” is a movie like that. There is hardly a thing I can say in its favor, except that I was cheered by nearly every minute of it. I cannot argue for the script, the direction, the acting or even the mummy, but I can say that I was not bored and sometimes I was unreasonably pleased. There is a little immaturity stuck away in the crannies of even the most judicious of us, and we should treasure it.

Ebert contrasts his judgement of the craft (script, direction, acting, effects) with his visceral delight. His pleasure was, by his own admission, unreasonable. That is, unlike many movies he loved, he cannot entirely explain or justify his delight.

There are a few ways to interpret this vis-a-vis taste. One is that taste isn’t objective or based on craft, it’s ineffable. Another is that Ebert didn’t have good enough taste to explain and justify why he liked The Mummy. Both of these are obvious nonsense. Read more »

Let’s grant, for the sake of argument, the relatively short-range ambition that organizes much of rhetoric about artificial intelligence. That ambition is called artificial general intelligence (AGI), understood as the point at which machines can perform most economically productive cognitive tasks better than most humans. The exact timeline when we will reach AGI is contested, and some serious researchers think AGI is improperly defined. But these debates are not all that relevant because we don’t need full-blown AGI for the social consequences to arrive. You need only technology that is good enough, cheap enough, and widely deployable across the activities we currently pay people to do.

Let’s grant, for the sake of argument, the relatively short-range ambition that organizes much of rhetoric about artificial intelligence. That ambition is called artificial general intelligence (AGI), understood as the point at which machines can perform most economically productive cognitive tasks better than most humans. The exact timeline when we will reach AGI is contested, and some serious researchers think AGI is improperly defined. But these debates are not all that relevant because we don’t need full-blown AGI for the social consequences to arrive. You need only technology that is good enough, cheap enough, and widely deployable across the activities we currently pay people to do.

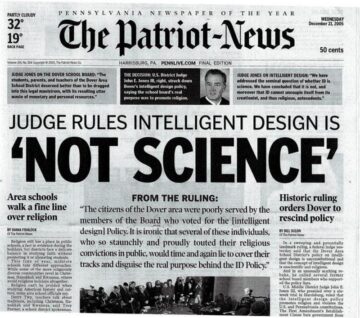

Last Saturday was the 20th anniversary of the day on which Judge John Jones III handed down

Last Saturday was the 20th anniversary of the day on which Judge John Jones III handed down

If poets are to take Imlac’s advice – and I’m not necessarily sure they should – then the proper season for doing so must be winter. No streaks of the tulip to distract us, and the verdure of the forest has been restricted to a very limited palette. Then the snow comes, and the world becomes a suggestion of something hidden, accessible only to memory or anticipation, like a toy under wrapping. Perhaps “general properties and large appearances” are accessible to us only as we gradually delete the details of life; we certainly don’t seem to have much access to them directly. This is knowledge by negation; winter is the supreme season for apophatic thinking.

If poets are to take Imlac’s advice – and I’m not necessarily sure they should – then the proper season for doing so must be winter. No streaks of the tulip to distract us, and the verdure of the forest has been restricted to a very limited palette. Then the snow comes, and the world becomes a suggestion of something hidden, accessible only to memory or anticipation, like a toy under wrapping. Perhaps “general properties and large appearances” are accessible to us only as we gradually delete the details of life; we certainly don’t seem to have much access to them directly. This is knowledge by negation; winter is the supreme season for apophatic thinking. Sughra Raza. Underbelly Color and Shadows. Santiago, Chile, Nov, 2017.

Sughra Raza. Underbelly Color and Shadows. Santiago, Chile, Nov, 2017.

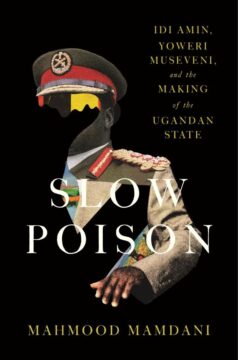

In June 1976, an Air France flight from Tel Aviv to Paris was hijacked by members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine along with two German radicals, diverted to Entebbe, Uganda, and received with open support from Idi Amin. There, the hijackers separated the passengers—releasing most non-Jewish travelers while holding Israelis and Jews hostage—and demanded the release of Palestinian prisoners. As the deadline approached, Israeli commandos flew secretly to Entebbe, drove toward the terminal in a motorcade disguised as Idi Amin’s own and stormed the building. In ninety minutes, all hijackers and several Ugandan soldiers were killed, 102 hostages were freed, and three died in the crossfire. The only Israeli soldier lost was the mission commander, Yoni Netanyahu.

In June 1976, an Air France flight from Tel Aviv to Paris was hijacked by members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine along with two German radicals, diverted to Entebbe, Uganda, and received with open support from Idi Amin. There, the hijackers separated the passengers—releasing most non-Jewish travelers while holding Israelis and Jews hostage—and demanded the release of Palestinian prisoners. As the deadline approached, Israeli commandos flew secretly to Entebbe, drove toward the terminal in a motorcade disguised as Idi Amin’s own and stormed the building. In ninety minutes, all hijackers and several Ugandan soldiers were killed, 102 hostages were freed, and three died in the crossfire. The only Israeli soldier lost was the mission commander, Yoni Netanyahu.