by Kevin Lively

In the six weeks since taking office, the Trump administration has moved with an alacrity boarding on mania, pursuing the tactical doctrine of Steve Bannon: flooding the zone. In a head spinning few weeks, the effort to reshape the federal government (i.e. make it small enough to drown in a bathtub), spearheaded by Elon Musk have done the following: stop all federal hiring, put all federal diversity equity and inclusion staff on leave, attempted to freeze trillions of dollars in federal funding, offered two million federal workers the option of being paid without working until September – then being fired, installed Elon loyalists inside the highly sensitive treasury payments system (Clinton’s secretary of labor was unamused), moved to cut 90% of USAID’s budget, moved to shut down the consumer financial protection bureau, et cetera, et cetera.

While many of these moves have been challenged by the courts, the sheer scale of this attempt to effectively destroy broad swathes of the federal government is nonetheless shocking. Surely such a broad based attack can’t really be in the interests of Trump’s voters and financial backers? For example, Veterans Affairs doctors are among the 2 million employees who received the offer to quit, and what is really to be gained by cutting funding for HIV medication for South Africa? If the goal was really to save money to address, say, the debt, then you would want to increase IRS resources not fire 6700 members of its staff. This raises the obvious question: “Whose interest is this actually in?”

As I discussed in my previous column, there is a rich history from which the Trump administration came, and the logic of these actions is no exception. In fact proposals to eliminate or reduce many of the functions of government have been widely discussed with varying degrees of enthusiasm among both conservative and liberal policy planners for decades. Albeit none have been able to act with as much zeal as we are now seeing. Most obviously we can look to Reagan as the first real fruition of this spirit. During the 1980 presidential debates he said quite plainly that he wanted to introduce tax cuts in order to reduce government spending. In his eight years, he reduced the top marginal tax rate from 73% to 28%, and cut the highest personal income tax bracket from 70% to 38.5%. This was an insufficiently enthusiastic attack for Pat Robertson. In Robertson’s 1988 presidential bid he promised to cut the budget by $100 billion while eliminating every single Carter holdover from among the 100,000 federal employees who could be terminated at will.

Clinton, although coming from the less enthusiastic side, still passed a substantial welfare cut in 1996 pushed on him by Newt Gingrich. This reform introduced work requirements and devolved the program down to the states as the scandal wracked TANF program. The effects were a rapid drop off in recipients of welfare and medicare: participation dropped by as much as 53% as early as 1998. Needless to say the Bush tax cuts continued the streak, and despite facing the worst financial and deficit crisis in modern memory, Obama made no moves to plug the massive hole in the federal budget from the previous decades of tax cuts on the wealthy. Biden, a hold over from the waning days of the New Deal, appeared to be a last gasp attempt to reverse this trend. Now Trump has shifted into an unrestrained overdrive of the most conservative elements.

If this argument holds, then it appears that there has been some tacit bipartisan consensus which has predominated over the last 40 years or so. Clearly this is a nuanced phenomena with many disagreements. However in broad strokes it seems clear that both parties seemed mostly content to let the government budget and its social programs erode. If this is true, then where did this consensus come from? Where does the disagreement lie between the liberal and conservative ends of the US Overton Window? By understanding this could a strategy be envisioned to shift the consensus to a direction which can stimulate badly needed government investment in the plethora of ills facing the country?

In an attempt to establish an intellectual and historical framework to think about this question I will focus on two topics. To establish the intellectual framework, in this article I will mostly focus on empirical research on political coalitions in America, namely how collections of economic interests and voters align around given parties and how the interests behind those coalitions evolve over time. To establish the historical framework I will start by describing the lead up to the pivotal re-alignments of the 1970s which I’ve pointed to previously, and the response of the liberal-internationalist coalition to it. In the follow up I will describe the response of the more conservative, domestic focused business community, the Powell memorandum, authored by soon to be Supreme Court Justice Lewis Powell in 1971. There I will detail the direct thru-line from this document to the dominance of right wing institutions today and the Project 2025 campaign to dismantle the regulatory state.

One of the most substantive and empirically backed analysts, that I’ve found so far at least, on political coalitions in the US is Thomas Ferguson, director of research at the Institute for New Economic Thinking. Nearly every election cycle since at least 1980, he has been putting out post-election analysis papers whose results one would expect to be widely reported and understood public knowledge. These studies meticulously document which sectors of the US economy gave money to which politicians and analyze what motives they may have for doing so.

This breakdown allows one to see for example that in the 2012 election Romney received the overwhelming percentage of contributions from mining, paper, chemicals, oil companies, private equity, banking and hedge funds while Obama received the largest support from Telecom, Silicon Valley and the Health Insurance industry. Similar breakdowns occurred in the 2016 election (non paywalled version), with the interesting flip that this time it was Clinton who received 90% of hedge fund contributions and 77% from private equity. Pollution heavy industries continued to favor Trump.

Now, cheeky memes aside, just tracking this money is not sufficient to say that there is any direct quid pro quo or that these elected representatives are beholden to their financiers. Just because, for example, 99.26% of coal industry funding went to Trump in 2016, doesn’t necessarily mean that’s the reason his first EPA director was someone who had sued the EPA on behalf of coal plants and promised to debate climate change as EPA director. Neither does it determine that his second EPA director was just a straight-up coal lobbyist. Trump legitimately may have put these people in office regardless of contributions. In fact many sectors of the economy give almost evenhandedly to both parties, such as the auto, oil, tobacco and chemical sectors in 2016. If one were to believe that political spending influences political decision making, this would be an good way to hedge bets. Alternatively it could also be argued as evidence against any explicit desire to “buy” a given politician, and instead such contributions are just civic minded activity on the part of citizens and corporations.

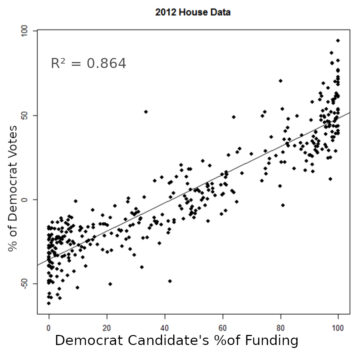

Regardless of decision making, there is also the question of whether or not such spending even produces substantial differences in election outcomes. One study by the Campaign Finance Institute/Bipartisan Policy Center Working Group for example states that “Decades of social science research consistently find a more limited role for campaign spending [than what the public perceives].” However in a 2018 study (non paywall) Ferguson and colleagues analyze every single Senate and House race from 1980 to 2014 and show a nearly uniformly consistent correlation between campaign expenditure for a given party and its percentage of the vote. The R² fit, which determines the strength of correlation in a data set, for nearly all of these elections is on the order of 0.8 (1 being a perfectly straight line). For the social sciences this is an astoundingly solid quantitative result.

The unifying work for this analysis is given in the 1995 book Golden Rule: The Investment Theory of Party Competition and the Logic of Money Driven Political Systems, in which the titular Investment Theory is laid out. Analyzing US industrial structure from the 1800s onward, Ferguson breaks down the coalitions of economic and social interests which coalesced into the five or so recognized Party Systems in the US: Federalists vs Jeffersonian Republicans, Jacksonian Democrats, Lincoln Democrats, the System of 1896, and the New Deal System which began to break down around the Reagan years. These systems are defined by collections of sectors of society and the economy which are stable across multiple electoral cycles, centering on particular political parties and platforms. Typically a single one of those parties is hegemonic, in that even when the opposition is in power, its policies are shaped by the prevalent zeitgeist. An example of this phenomena is when Eisenhower, the first republican elected since FDR – a 20 year span – said in a private letter that “Should any party attempt to abolish social security and eliminate labor laws and farm programs [New Deal Policies], you would not hear of that party again in our political history. There is a tiny splinter group of course, that believes you can do these things […] Their number is negligible and they are stupid”.

By the time we get to the New Deal, the industrialized economy and government begins to coalesce into a series of economic factors which are still dominant today. It’s important to remember that US Labor history up to this point was arguably the most violent of any industrialized country. For instance mining corporations ran essentially private military and police outfits. During the Coal Wars such groups were responsible for a series of massacres of coal miners and their families as in Ludlow in 1914, which is by no means an isolated incident. For comparison by 1891 Bismarck’s Germany had established compulsory healthcare insurance for industrial workers, accident insurance, and an old-age and disability pension — to stave off socialist revolution. This is to say that the level of profound change for working people in the US which the New Deal enacted can hardly be overstated.

Ferguson argues that the forces which lead to this apparent about-face of US labor policy came ultimately from the post WWI ascendance of internationally oriented, capital intensive industries such as banking, and crucially oil and auto companies who were supplying to the recovering European market. In these industries, the argument goes, wages as a fraction of the total costs of production are relatively low. Therefore introduction of protections for unionization and social security posed more of an acceptable cost to the benefit of stable labor relations. Crucially due to labor shortages and a resurgence of strikes after the war, unions had rebuilt themselves and for practically the first time had a sympathetic ear in the white house. This combination of internationalist, economically liberal, capital-intensive businesses in favor of free-trade, alongside labor unions provided the framework for New Deal Democrats for the bulk of the middle of the 20th century.

After WW2 the predominance of the liberal-internationalist coalition seemed irrevocable. The Bretton Woods System had established the US dollar as the worlds reserve currency. The US Military controlled both sides of both oceans and in the words of the eminent state department planner George Kennan in a 1948 policy paper “we have about 50% of the world’s wealth but only 6.3% of its population”. This introduced a new dimension to the internationalist liberal-economic order, continuing in the words of Kennan: “Our real task in the coming period is to devise a pattern of relationships which will permit us to maintain this position of disparity without positive detriment to our national security.” Central to this was keeping foreign markets, in particular Europe, available for US exporters. Thus came into the coalition a strong interventionist streak — beyond keeping Central and South American resources free for US business investment which appears to have been universally agreed upon since Monroe.

Despite efforts by LBJ to extended the New Deal by appeals to labor with his war on poverty programs, by the 1970s cracks had begun to appear. Government and businesses were struggling to process the wave of popular activism which had fundamentally transformed american society over the course of the 1960s. By 1968 so-called race riots and student protests had reached such a pitch that soldiers had to be called in to guard the capitol. Simultaneously, economic recovery in Japan and Europe had led to tensions in the international monetary system. Trade surpluses from Japan and Germany began to threaten US exporters and inflation mounted. When the US ran a trade deficit for the first time in 1971, Nixon responded by taking the US dollar off the gold standard, destroying the fixed currency exchange system. He then introduced a suite of highly interventionist economic policies including 10% tariffs on all imported goods, wage-price controls, and pressured Japan and Germany to reduce trade barriers. While many domestic manufacturers benefited, the sectors of the economy which benefited more from free-trade internationalism — mostly banks and multinationals — were appalled and began organizing to defend their interests.

These two factors of domestic unrest and a wavering support for internationalism led much fretting in policy circles of how to respond. For the sake of simplicity I will focus on two primary poles which themselves have complex coalitions around them. Starting on the internationalist front, in 1973 David Rockefeller founded the Trilateral Commission, an organization dedicated to improving relations between Japan, Europe and the USA. Their seminal publication in 1975 is entitled The Crisis of Democracy. In his chapter on conditions in the US, Samuel Huntington states that:

“The 1960s also saw [..] a marked upswing in other forms of citizen participation, in the form of marches, demonstrations, protest movements, and ’cause’ organizations (such as Common Cause, Nader groups, and environmental groups.) The expansion of participation throughout society was reflected in the markedly higher levels of self-consciousness on the part of blacks, Indians, Chicanos, white ethnic groups, students, and women — all of whom became mobilized and organized[.] Previously passive or unorganized groups in the population now embarked on concerted efforts to establish their claims to opportunities, positions, rewards, and privileges, which they had not considered themselves entitled to before.”

Huntington briefly praises the capacity of the US Democratic system to absorb such demands (from seemingly the entire population besides upper-middle class white men. . .). Nonetheless he quickly goes on to chide that the balance between authority and democracy had become disequilibrated:

“The essence of the democratic surge of the 1960s was a general challenge to existing systems of authority, public and private […] People no longer felt the same compulsion to obey those whom they had previously considered – superior to themselves in age, rank, status, expertise, character, or talents. […] Truman had been able to govern the country with the cooperation of a relatively small number of Wall Street lawyers and bankers. By the mid-1960s, the sources of power in society had diversified tremendously, and this was no longer possible.”

Specifically he details the expansion of government expenditure after WWII and notes that while the military build-up necessary to maintain the preferred internationalist order was sustainable for the duration of the Korean war and the beginning of Vietnam, that LBJs war on poverty proposals led to “massive increases in governmental expenditures to provide cash and benefits for particular individuals and groups within society rather than in expenditures designed to serve national purposes vis-a-vis the external environment”.

His conclusion was that since “the effective operation of a democratic political system usually requires some measure of apathy and non involvement on the part of some individuals and groups”, that “some of the problems of governance in the United States today stem from an excess of democracy” and that what was needed was “a greater degree of moderation in democracy”.

These comments are not just words floating in the ether. The author of this chapter became a member of the Carter administration, and in fact Carter himself and many more of his senior staffers were members of this organization. This was (and often still is) public and perfectly mainstream political thought, even if not necessarily spoken loudly at campaign rallies. This is essentially the “left” response to the changes of the 60s and 70s. The conservative business response I will address in the next column.

For now though, if the conditions we have today are due to a greater degree of moderation in democracy, then perhaps we should instead push back towards an excess.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.