by Richard Farr

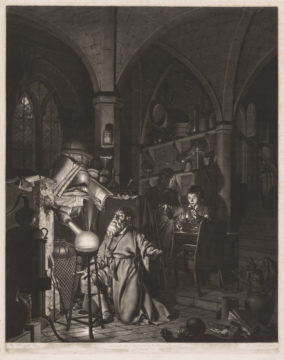

Lucky you, reading this on a screen, in a warm and well-lit room, somewhere in the unparalleled comfort of the twenty-first century. But imagine instead that it’s 800 C.E., and you’re a monk at one of the great pre-modern monasteries — Clonard Abbey in Ireland, perhaps. There’s a silver lining: unlike most people, you can read. On the other hand, you’re looking at another long day in a bitterly cold scriptorium. Your cassock is a city of fleas. You’re reading this on parchment, which stinks because it’s a piece of crudely scraped animal skin, by the light of a candle, which stinks because it’s a fountain of burnt animal fat particles. And your morning mug of joe won’t appear at your elbow for a thousand years.

Lucky you, reading this on a screen, in a warm and well-lit room, somewhere in the unparalleled comfort of the twenty-first century. But imagine instead that it’s 800 C.E., and you’re a monk at one of the great pre-modern monasteries — Clonard Abbey in Ireland, perhaps. There’s a silver lining: unlike most people, you can read. On the other hand, you’re looking at another long day in a bitterly cold scriptorium. Your cassock is a city of fleas. You’re reading this on parchment, which stinks because it’s a piece of crudely scraped animal skin, by the light of a candle, which stinks because it’s a fountain of burnt animal fat particles. And your morning mug of joe won’t appear at your elbow for a thousand years.

What could be worse than the cold, the fleas, the stink, and no coffee? Well. The script you are reading is minuscule, to save ink and space, and it’s written in scriptio continua. That’s right: you are plagued by headaches because spacesbetweenthewordsaremodernconveniencesthathavelikepunctuationandcoffeeandreadingglassesanddeodorantforthatmatternotyetbeeninvented. Even for someone like you, with years of prayer and special training under your greasy rope belt, this is a constant source of difficultyambiguityfrustrationeyestrainanderrer.

Thank goodness for modernity, eh? Except for one strange fact. In our smugly “digital” age, our numbers are still waiting for modernity to happen. Read more »

Harry Frankfurt died on July 16, 2023. As a philosophy student I came to appreciate him for his work on freedom and responsibility, but as a high school word nerd, I came to know him the way other shoppers did: as the author of one of those small books near the bookstore checkout line. That book, On Bullshit, had exactly the right title for impulse-buying, which has to explain how Frankfurt became a bestselling author in a field not known for bestsellers.

Harry Frankfurt died on July 16, 2023. As a philosophy student I came to appreciate him for his work on freedom and responsibility, but as a high school word nerd, I came to know him the way other shoppers did: as the author of one of those small books near the bookstore checkout line. That book, On Bullshit, had exactly the right title for impulse-buying, which has to explain how Frankfurt became a bestselling author in a field not known for bestsellers.

I had my first experience with Daylight Saving Time when I was 9 or 10 years old and living in Phoenix. Most of the country was on DST, but Arizona wasn’t. I knew DST as a mysterious thing that people in other places did with their clocks that made the times for television shows in Phoenix suddenly jump by one hour twice a year. In a way, that wasn’t a bad introduction to the concept. During DST, your body continues to follow its own time, as we in Phoenix followed ours. Your body follows solar time, and it can’t easily follow the clock when it suddenly jumps forward.

I had my first experience with Daylight Saving Time when I was 9 or 10 years old and living in Phoenix. Most of the country was on DST, but Arizona wasn’t. I knew DST as a mysterious thing that people in other places did with their clocks that made the times for television shows in Phoenix suddenly jump by one hour twice a year. In a way, that wasn’t a bad introduction to the concept. During DST, your body continues to follow its own time, as we in Phoenix followed ours. Your body follows solar time, and it can’t easily follow the clock when it suddenly jumps forward.

Unspeakable horrors transpired during the genocide of 1994. Family members shot family members, neighbours hacked neighbours down with machetes, women were raped, then killed, and their children forced to watch before being slaughtered in turn. An estimated 800,000 people were murdered in a country of (then) eight million. Barely thirty years have passed since the Rwandan genocide. Everywhere, there are monuments to the dead, but as an outsider I see no trace of its shadow among the living.

Unspeakable horrors transpired during the genocide of 1994. Family members shot family members, neighbours hacked neighbours down with machetes, women were raped, then killed, and their children forced to watch before being slaughtered in turn. An estimated 800,000 people were murdered in a country of (then) eight million. Barely thirty years have passed since the Rwandan genocide. Everywhere, there are monuments to the dead, but as an outsider I see no trace of its shadow among the living.

Barbara Chase-Riboud. Untitled (Le Lit), 1966.

Barbara Chase-Riboud. Untitled (Le Lit), 1966.

One of the easy metaphors, easy because it just feels true, is that life is like a river in its flowing from then to whenever. We are both a leaf floating on it, and the river itself. Boat maybe. Raft more likely. But those who know such things say there is a river beneath the river, the hyporheic flow. “This is the water that moves under the stream, in cobble beds and old sandbars. It edges up the toe slope to the forest, a wide unseen river that flows beneath the eddies and the splash. A deep invisible river, known to its roots and rocks, the water and the land intimate beyond our knowing. It is the hyporheic flow I’m listening for.” The person speaking is Robin

One of the easy metaphors, easy because it just feels true, is that life is like a river in its flowing from then to whenever. We are both a leaf floating on it, and the river itself. Boat maybe. Raft more likely. But those who know such things say there is a river beneath the river, the hyporheic flow. “This is the water that moves under the stream, in cobble beds and old sandbars. It edges up the toe slope to the forest, a wide unseen river that flows beneath the eddies and the splash. A deep invisible river, known to its roots and rocks, the water and the land intimate beyond our knowing. It is the hyporheic flow I’m listening for.” The person speaking is Robin There is a scene near the end of First Reformed, the 2017 film directed by Paul Schrader, where the pastor of a successful megachurch says to the pastor of a small, sparsely attended church:

There is a scene near the end of First Reformed, the 2017 film directed by Paul Schrader, where the pastor of a successful megachurch says to the pastor of a small, sparsely attended church: