by Bill Murray

With earth set on a slow rolling boil through the rest of the summer, now might be a good time to mentally transport oneself to the cold. How’s about a winter weather sailor’s tale?

St. John’s, Newfoundland and the Grand Banks

People feel pain but too often fail to appreciate its absence. There are solid, evolutionary, survival-dependent reasons to prioritize pain – flee that sabre-toothed tiger, and fast! – but how much fuller life would be if we could celebrate time spent pain free. And what do you know, here is an island full of people who do just that. Welcome to “The Rock.”

Newfoundland marches to the beat of its own drummer, or at least to the ticking of its own clock. An hour and a half ahead of the U.S. east coast, the island they call “The Rock” is an island alone. No one shares Newfoundland Standard Time, which is a half hour ahead of the rest of Atlantic Canada and a half hour behind the nearby French territory of Saint-Pierre et Miquelon.

At 400,000 square kilometers, Newfoundland and Labrador comprise a province triple the size of the other Canadian maritime provinces of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island combined. Newfoundland is the sixteenth largest island in the world, larger than Iceland, or Cuba. Read more »

I met Kseniia during my second visit to Ukraine, in June 2023. The moment I met her, I knew that this thirty-four-year-old woman is a special one. Kseniia belongs to the type of women who made Molotov cocktails to help defend Kyiv in March 2022. “I had some romantic idea to create these Molotov cocktails, because I heard that it might come to urban warfare, and I wanted to help. We spent a whole day making them, but the smell of petrol was awful.” Nevertheless, Kseniia made several boxes.

I met Kseniia during my second visit to Ukraine, in June 2023. The moment I met her, I knew that this thirty-four-year-old woman is a special one. Kseniia belongs to the type of women who made Molotov cocktails to help defend Kyiv in March 2022. “I had some romantic idea to create these Molotov cocktails, because I heard that it might come to urban warfare, and I wanted to help. We spent a whole day making them, but the smell of petrol was awful.” Nevertheless, Kseniia made several boxes.

Sughra Raza. Self-portrait at Itaimbezinho Canyon, Brazil, March 2014.

Sughra Raza. Self-portrait at Itaimbezinho Canyon, Brazil, March 2014.

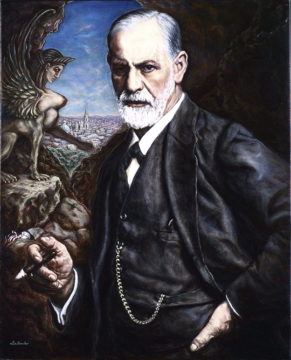

I picture the LORD God as a child psychologist—very much of a type, vaguely professorial, plucked from the ’50s. Picture him with me: shorn and horn-rimmed, his fingernails immaculate, he’s on his way to a morning appointment. As he kneels in the garden to tie his shoe, his starched white shirtfront strains against his gut.

I picture the LORD God as a child psychologist—very much of a type, vaguely professorial, plucked from the ’50s. Picture him with me: shorn and horn-rimmed, his fingernails immaculate, he’s on his way to a morning appointment. As he kneels in the garden to tie his shoe, his starched white shirtfront strains against his gut.

The first

The first

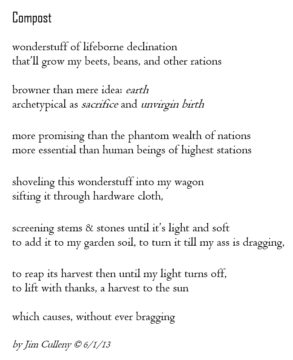

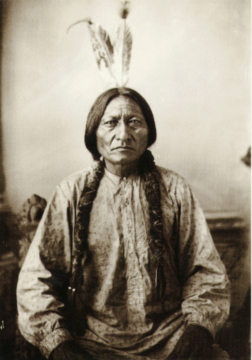

Jeffrey Gibson. Chief Black Coyote, 2021.

Jeffrey Gibson. Chief Black Coyote, 2021.