by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

What are the chances that one of the greatest painters alive– a genius of portraiture, no less– would arrive at the court of the most infamous king in British history at the precise moment when the king began sending his royal wives to the chopping block?

Henry VIII. Even today, we can close our eyes and conjure up his dazzlingly rotund image. Those shapely legs in their white hose, adorned with courtly garter. And what about his perfect eyebrows and soft cheeks? The only reason we can do this conjuring is the skill of the painter Hans Holbein the Younger, who arrived in London just when all the fun started.

Holbein painted Henry so vividly. So evocatively. Facing straight on, legs set wide apart, his eyes are locked on the viewer. This is a vision of power. A lion about to pounce. In his puffed sleeves and doublet, the king is dripping in silk, gold, and gemstones. Holbein’s Henry is not just a portrait of the King but is an icon of power and excess.

And I’m sure I don’t need to point out the codpiece.

It was not just Henry whom Holbein painted either; for as Franny Moyle says in her wonderful Holbein biography, The King’s Painter, which came out earlier this year, every aristocratic Tom, Dick and Henry wanted a portrait painted by the great German artist.

In 1537, Holbein became Henry’s official court painter. With Leonardo at the French court in Amboise and Titian in Madrid, it was obvious that Henry needed a painter of his own. It bears considering how extraordinary were the times. As Julian Norwich writes in his book Four Princes, Henry VIII was not just sharing the world stage with the King of France, Francis I, and the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, but he was also a contemporary of Suleiman the Magnificent, who needs no introduction.

But for Henry, this sultan was a remote and hazy presence. During his long reign, Henry was in a constant tug of war with Francis and Charles –Charles, who was also the nephew of Henry’s first wife Catherine of Aragon, whom Henry had so mistreated. Still, England was far from the battles that Francis and Charles had with the Ottoman Empire. So, this left Henry with more time to obsess on his domestic issues, not to mention things to do with that codpiece.

His first wife, Catherine of Aragon, had already been cast aside after reaching menopause so that Henry could try to father a son. Holbein arrived in England as Henry’s “great matter” to marry Anne Boleyn had turned into being a “great mistake.” So the king got rid of her along with his counselor Cardinal Woolsey, breaking with Rome in the process. When at last he had found the wife of his dreams in Jane Seymour (ie, one who would bear him a son), she died a few weeks after her ordeal by childbirth. But he had his boy. At last.

Henry’s life had been dominated by courtly love and romances. It was as if he was living in a fantasy version of King Arthur’s court. Indeed, for the times, it was surprising that Henry remained committed to unions based on love. Having become a laughingstock amongst the kings of Europe, who all formed political marriage alliances as a matter of course, King Henry had wed not once—but three times for true love. But at the death of his beloved Jane Seymour, the Reformer Thomas Cromwell, who had stepped in to fill Woolsey’s shoes after his fall from grace, was pushing for a political union with a Protestant state.

And that was where Holbein stepped in.

In addition to his portraits of the King and Queen Anne Boleyn, Holbein would be sent on missions to paint eligible princesses around Europe. Not an easy task, for to flatter a lady would be to hoodwink the King, never a forgiving man even in the best scenario. But to be brutally honest could change the fate of kingdoms. His large portrait of Christina, the Duchess of Milan, considered by some to be the finest portrait ever created, had Henry so pleased by this prospective bride that he ordered music and dancing performed at court nonstop for days.

Holbein would paint many of the famous people of Henry’s day– from the great humanist Thomas More, who had been the painter’s original benefactor in London, to the unattractive Thomas Cromwell. There were commissions from merchants of the Hanseatic League in London, not to mention an extraordinary painting, known to us today as The Ambassadors— of two French friends standing behind a white blur that snaps into focus if you find just the right spot in which to stand. It is a human skull.

When time permitted, Holbein would also paint aristocrats like Simon George of Cornwall, a staggeringly sexy picture of the gentleman in his beautiful feather hat, holding a red carnation . Or there is the less-sexy –but equally marvelous– Anne Lowell against a surreal blue ground with curling green fig branches, her pet squirrel held in her hands and a black starling on her shoulder as if whispering in her ears.

It is this last picture that became the poster image of the recent Holbein exhibition at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles. “Holbein: Capturing Character” seeks to explore the creative ways Holbein sought to portray his subjects, not just in their realistic likeness –which could be problematic, after all– but in their full character.

How to depict a person’s inner life? For the best portraits must go beyond outward likeness to convey something of the person. For King Henry, it was the romance and mystique of wealth, power, and kingship. In the case of Christina of Denmark, reputed to be one of the greatest beauties of her day, we see a woman so lively that she doesn’t require fancy dresses or jewels. Depicted in the black of mourning, for she had been widowed at just sixteen years of age, her mischievous and teasing personality comes full force. When asked whether she would like to become the next Mrs Henry VIII, she noted with regret that she did not have two heads…. having only one, she preferred to steer clear of Henry and his chopping block. Her character and personality are in full display in Holbein’s portrait. Just looks at her expression and those hands.

2.

To be painted by Holbein, can you imagine it?

Since leaving Japan in 2011, I have become interested in portrait paintings– in particular, in the late Medieval and early Renaissance Donor Pictures. A sub-category of sacra conversazione paintings (in which the Enthroned Virgin and Jesus are seen in conversation with various saints), in donor pictures you find painted in a corner of the scene, a portrait of the painting’s patron. Sometimes depicted with a spouse and often the donors are painted on their knees in prayer. Some of my favorite examples of donor paintings include the van Eyck’s The Virgin and Child with Canon van der Paele, 1434–36 in Bruges and The Montefeltro Altarpiece or the Brera Madonna by Piero della Francesca in Milan. And of course, the Madonna della Vittoria by Andrea Mantegna in the Louvre. This is a picture I have stood in front for hours. It is the one with the white bird—and how did that white cuckoo from Australia find its way into a painting created in 1496? Beneath a high throne decorated in pearls and weavings, sits Mary.

Like a wormhole connecting discrete and distant points in time, these pictures are stunningly transportive. The church authorities, maybe not surprisingly, clamped down on this practice and the early Renaissance donor portraits disappeared. I had never noticed them until recently when I started to really look at them. And the more I looked, the more I began to fantasize about what it would be have my own portrait painted like that amongst the saints. Or a better way of saying this is that if I lived back then and more to the point, had been rich beyond belief, how certainly I would have desired to be painted like that.

Is it not the ultimate selfie?

Or maybe it is the ultimate non-selfie.

We live in an age of rampant images. But I wonder what would it be like to have only one image of oneself? Because I lost all my old photos in a wreck, I don’t have many photographs of myself in Japan, or of my son when he was small. The remaining images I have–in film negatives and a few I uploaded to social media before the disaster– are so precious. What this means is that unlike young people today, I really don’t have reams of pictures of myself. I don’t much mind…. In fact, I would rather possess just one portrait in oil.

Even though I hate having my picture taken, I plotted a re-enactment of Jan van Eyck’s The Arnolfini Portrait. As a celebration the joy of my second marriage, but in pixels, not brush-strokes. Much like Holbein a hundred years later, van Eyck traveled for work. His boss, unlike Henry VIII, was known for his mad pranks. In the good old days, kings and dukes were known to play around, and an artist working for Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy might occasionally be asked to join the fun. Job titles were more flexible back then: for in addition to spying missions for his liege, van Eyck helped create decorations for the Duke’s fabulous parties and practical jokes. These included rainmaking devices that squirted water on ladies from below, books that sprayed soot on unsuspecting readers, and magical mirrors.

Holbein also planned parties and created statement pieces, like the table fountain commissioned by Anne Boleyn. He designed the royal cutlery and a palace fireplace and even had a hand in creating the displays for her coronation processions on the 31st of May and 1st June 1533. His tableau, erected in Gracechurch Street, represented Apollo and the Muses on Mount Parnassus.

Hanging near to Holbein’s fascinating Ambassadors, van Eyck’s Arnolfini can be found in the National Gallery in London. The painting is smaller than I expected. But it is such an extraordinary double portrait. And more promising to emulate, as we are lacking in saints. I looked for a green gown for me and a hat and dark coat for Chris. We already have our sweet puppy and a chandelier. All that was missing was the convex mirror. But how hard could that be to find? Her emerald gown stole my breath away, though I have read that it was Mr. Arnolfini’s outfit where the real money lay. Still, that green dress….. And the way she stands almost overwhelmed by the layers–blue under a fur-lined merino wool green gown: it is reminiscent of formal kimono. I had many chances to wear kimono in Japan but I could not imagine spending so much money on a piece of clothing. But looking at the lady in the luxurious green gown, I felt how glorious it would be to stand in her shoes.

Five years later, during the pandemic, I was delighted to see the way people were taking up the call by the Getty Museum to re-enact famous pictures. Missing museums terribly, like a lot of people, I loved seeing these, and so many were portraits. This drive for humanity to create was one of the themes in Emily St. John Mandel’s apocalyptic novel Station Eleven. It is how we speak to each other without words and across time and space.

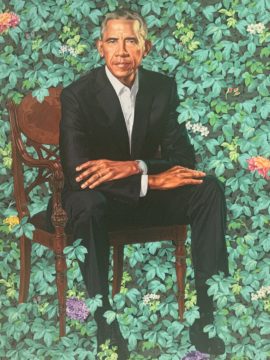

Despite the wonderful pandemic re-enactments that flooded my social media feeds, I had all but forgotten about my own plans to re-enact the Arnolfini painting, when another famous portrait came to town– right on the heels of Holbein! Like a lot of people, the unveiling of Kehinde Wiley’s presidential portrait of Barack Obama grabbed my attention. I fell in love with the picture the first time I saw it online and have longed to see it in person. So, I was thrilled to find out it was here in Los Angeles.

Before the portraits, I had been impressed with the Obama’s dedication to contemporary art and their exciting aesthetic tastes–bringing into the White House works like Alma Thomas’ Resurrection and Glenn Ligon’s Black Like Me #2.

I first heard of artist Kende Wiley from his Memling Series, which are beautifully created oils of people he met while living in Harlem painted in conversation with works by Renaissance painter Hans Memling, who was himself known to have painted portraits of ordinary people. Last year, the Memling Museum in Bruges, which is housed in the old 12th century Saint John’s Hospital, put on an exhibition of works by contemporary artist inspired by Memling (Video), including the complete Memling Series by Wiley. He also has a large scale work kept in the Brooklyn Museum called Napoleon Leading His Army Over the Alps that I am dying to see. Napoleon, as is well known never crossed the Alps on a rearing stallion and instead followed behind the army on a mule several days later. Wiley, therefore, has taken a propagandist image by 19th century Jacques-Louis David, and turned it on its head.

He is such an exciting painter, whose command of craft is as off-scale– as his vision. So, I couldn’t wait to see the Barrack Obama Portrait.

Both Portraits have become objects of secular pilgrimage and are touring the nation, where they are drawing massive crowds. Michelle’s was painted by Amy Sherald. I got my first sighting of it in the twitter frenzy caused by a picture of a little girl standing in awe at the foot of Michelle Obama’s portrait: The resulting media sensation had led the girl’s mother to hire a publicist to manage all the requests for interviews. Mrs. Obama, the little girl told Ellen DeGeneres in front of a live national audience, was probably a “queen.” (Article in Atlantic). There was also this picture on Instagram of a hand-drawn picture by a guard at the National Portrait Gallery describing how an elderly lady had gotten on her knees and prayed in front of the portrait in the company of other visitors: “No other painting gets the same kind of reactions. Ever.”

At LACMA, where the portraits will be until early January, you are allowed to get close. And approaching Wiley’s Portrait of Barack, I felt awe. There is the great man, sitting in a wooden chair like the Presidential Portrait of Abraham Lincoln. Sitting forward in his chair, much attention is on his hands, which are unbelievably beautiful. He is attentive and poised. Barack’s extraordinary presence bears down on viewers. He sits in a flowery world. There are African blue lilies representing his father in Kenya; white jasmine for his childhood in Hawaii; and chrysanthemums, which are the official flower of Chicago where Obama trained as a community organizer. This is a sacra conversazione with the natural world.

Can a portrait represent a life and offer a legacy? Facebook and Instagram are popular because we want to have some control over how we are seen by others. But perhaps between the subject and the portrait painter, there is a singular bond. Long after their subjects are gone, these images will move us. With the deepest kind of looking, great artists can transfer a little bit of the beauty, the dignity, the essence of a person onto the canvas.

To be truly seen, even once, would be a gift.

Video: A Stitch in Time in the Arnolfini Portrait

Hannah Gadsby: why I love the Arnolfini Portrait, one of art history’s greatest riddles

The Obama Portraits Have Had a Pilgrimage Effect

One year after Kehinde Wiley’s and Amy Sherald’s paintings were unveiled, the director of the National Portrait Gallery reflects on their unprecedented impact.

By Kim Sajet

The Internet Is Restaging Famous Paintings While Museums Are Closed

The Getty, Metropolitan Museum, and Rijksmuseum have challenged their followers to creatively recreate famous works in their collections. In HYPERALLERGIC by Hakim Bishara

New Yorker: Where Did that White Cuckoo Come from?

Books:

The King’s Painter: The Life of Hans Holbein

by Franny Moyle

Holbein: Capturing Character

Getty Museum Catalogue

GIRL IN A GREEN GOWN

by Carola Hicks

Jan Van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait: Stories of an Icon

by Linda Seidel

The Obama Portraits

by Taina Beatriz Caragol-Barreto, Richard J. Powell, Dorothy Moss, Kim Sajet, Thelma Golden

Huntington Museum Kehinde Wiley: A Portrait of a Young Gentleman

Top Reads 2021: Hummingbirds and Holbein

.