by Michael Liss

Nearly 250 years is not quite Shakespeare, but if The Wealth of Nations were a play, we would say it has had a pretty good run. Is it a dusty old warhorse, to be read while sitting in a winged-back chair with a snifter of brandy, or still relevant today? Can it solve the (deep) problems of the present and future? Is our almost faith-bound devotion to market forces still justified, or are new approaches needed?

A heavy topic requires heavyweights, and I found them at this past November’s “Center on Capitalism and Society,” at Columbia University’s 20th Anniversary Conference. The topic: Economy Policy and Economic Theory for the Future

The two-day event assembled a formidable crew of speakers, headlined by three Nobelists for Economics: Joseph Stiglitz (2001), Eric Maskin (2007) and Edmund Phelps (2006). They were joined by a “supporting cast” of 15 others, also heavyweights in their field, including the sociologist and urbanist Richard Sennett, the financial journalist Martin Wolf, Finnish philosopher Esa Saarinen, Ian Goldin of Oxford, economists Roman Frydman and Jean-Paul Fitoussi, Carmen Reinhart of the World Bank, and Jeffrey Sachs of Columbia and the UN.

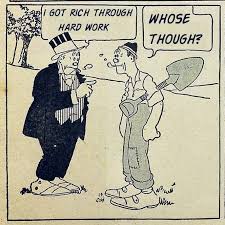

In short, there were a lot of credentials in the room (either in person or remotely) and a number of extremely compelling presentations, but it is Sachs whom I want to talk about. He spoke first, after opening remarks by the extraordinary Ned Phelps (nearing 90, still writing, still speaking, and still mentoring and inspiring), and I assume that the choice was a tactical one. The organizers clearly anticipated that Sachs would do what Sachs does: devote his time to lobbing a little hand grenade into the proceedings: Capitalism, to his way of thinking, particularly the Anglo-Saxon version of Capitalism practiced in the United States, was no longer capable of taking on the big, global challenges. Read more »

Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations begins with this claim:

Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations begins with this claim: I just read Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations for the first time. Not every word. It’s over a thousand pages, and there are long “Digressions” (Smith’s term) on matters such as the history of the value of silver, or banking in Amsterdam, which I simply passed over. I was mainly interested in what Smith has to say about work, so I also merely skimmed some other sections that seemed to have little relevance to my research. Time and again, though, I found myself getting sucked into chapters unrelated to my concerns simply because the topics discussed are so interesting, and what Smith has to say is so thought-provoking. Reading the book is also made easier both by Smith’s admirably lucid writing and by the brief summaries of the main claims being made that he inserts throughout at the left-hand margin.

I just read Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations for the first time. Not every word. It’s over a thousand pages, and there are long “Digressions” (Smith’s term) on matters such as the history of the value of silver, or banking in Amsterdam, which I simply passed over. I was mainly interested in what Smith has to say about work, so I also merely skimmed some other sections that seemed to have little relevance to my research. Time and again, though, I found myself getting sucked into chapters unrelated to my concerns simply because the topics discussed are so interesting, and what Smith has to say is so thought-provoking. Reading the book is also made easier both by Smith’s admirably lucid writing and by the brief summaries of the main claims being made that he inserts throughout at the left-hand margin.