by Ed Simon

What then is time? If no one asks me, I know what it is.

If I wish to explain it to him who asks, I do not know. —Augustine, Confessions (397)

Time is what keeps everything from happening all at once. —Richard Cummings, The Girl in the Golden Atom (1922)

Twenty-six years ago, on a late-afternoon, late-summer sojourn down Liverpool’s Bold Street, a High Street of dark pubs and record stores, Donner kebab counters and chip shops, Frank accidentally walked into 1965. On his idyl perambulations to meet up with his wife at Waterstone’s, where she was grabbing a copy of Trainspotting, and Frank noticed a different slant of light, an alteration in the atmosphere, a variation in the sounds from the street, a drop in temperature. The summer odor of warm beer and fetid air replaced with the crispness of Christmas time. Approaching the bookstore, the Cranberries blaring on the music system, and mid-tune it’s replaced with a tinny radio playing a Herman’s Hermits number. Bold Street’s pedestrians were no longer wearing Oasis and Blur t-shirts, now they were men in boating jackets and mop tops, women in Halston dresses and pixie cuts. The road no longer paved, but cobblestoned. Frank noted that the Waterstone’s façade was now of a shop named “Cripps,” a woman’s clothing store that had been on this spot but closed decades before. Just as he crossed the threshold, and Cripps was abruptly transformed back into a bookstore. Misapprehension, misconception, misinterpretation? Hallucination or hoax? Vortex or ghosts? As paranormal writer Rodney Davies helpfully opines in Time Slips: Journeys into the Past and Future, “One theory state that past, present, and future are all one… But our limited consciousness can only experience time by being in what we know as ‘the present.’” Mayhap.

Twenty-six years ago, on a late-afternoon, late-summer sojourn down Liverpool’s Bold Street, a High Street of dark pubs and record stores, Donner kebab counters and chip shops, Frank accidentally walked into 1965. On his idyl perambulations to meet up with his wife at Waterstone’s, where she was grabbing a copy of Trainspotting, and Frank noticed a different slant of light, an alteration in the atmosphere, a variation in the sounds from the street, a drop in temperature. The summer odor of warm beer and fetid air replaced with the crispness of Christmas time. Approaching the bookstore, the Cranberries blaring on the music system, and mid-tune it’s replaced with a tinny radio playing a Herman’s Hermits number. Bold Street’s pedestrians were no longer wearing Oasis and Blur t-shirts, now they were men in boating jackets and mop tops, women in Halston dresses and pixie cuts. The road no longer paved, but cobblestoned. Frank noted that the Waterstone’s façade was now of a shop named “Cripps,” a woman’s clothing store that had been on this spot but closed decades before. Just as he crossed the threshold, and Cripps was abruptly transformed back into a bookstore. Misapprehension, misconception, misinterpretation? Hallucination or hoax? Vortex or ghosts? As paranormal writer Rodney Davies helpfully opines in Time Slips: Journeys into the Past and Future, “One theory state that past, present, and future are all one… But our limited consciousness can only experience time by being in what we know as ‘the present.’” Mayhap.

If you are the sort who absent-mindedly scrolls through accounts of the occult with dubious provenance, or as has spent innumerable hours listening to Art Bell’s Coast to Coast A.M., if you’ve ever heard of “John Titor” and wanted to believe, then you may already be familiar with Frank’s temporal flickering in the “Liverpool Time Slip.” Not the only such anomalies – there are accounts of tourists coming upon Marie Antoinette’s retinue while at Versailles and of guests in Cornish manor houses wandering into the seventeenth-century, backroad drivers in Arizona overtaken by futuristic vehicles and London streets destroyed by the Luftwaffe restored to pre-war completeness. Read more »

When I heard that Chicago will host the 2024 Democratic National Convention next August, (August 19-22,) it brought back a flood of memories. Memories, not only of the convention itself, but of the 60’s. “The 60’s” did not exactly span the decade but began in 1963 , when John F Kennedy was shot, and ended in 1975, when the war in Vietnam ended. During this relatively short period, our country went through a large number of societal changes, including political changes, changes in gender stereotypes, in racial interactions, in acceptable speech, in sexual mores. This was the time when we Baby Boomers came of age, when the 76 million Americans born between 1946 and 1954, began to flex their muscles and recognize how much they could accomplish, and what a loud voice they had when acting as a group. For example, they influenced clothing styles and music. They had tremendous purchasing power, as most of the clothing for sale after the 60’s was more appropriate for a-19–year-old than for a 40 or 50- year old American!

When I heard that Chicago will host the 2024 Democratic National Convention next August, (August 19-22,) it brought back a flood of memories. Memories, not only of the convention itself, but of the 60’s. “The 60’s” did not exactly span the decade but began in 1963 , when John F Kennedy was shot, and ended in 1975, when the war in Vietnam ended. During this relatively short period, our country went through a large number of societal changes, including political changes, changes in gender stereotypes, in racial interactions, in acceptable speech, in sexual mores. This was the time when we Baby Boomers came of age, when the 76 million Americans born between 1946 and 1954, began to flex their muscles and recognize how much they could accomplish, and what a loud voice they had when acting as a group. For example, they influenced clothing styles and music. They had tremendous purchasing power, as most of the clothing for sale after the 60’s was more appropriate for a-19–year-old than for a 40 or 50- year old American!

Nanni Moretti has always been a melancholic in denial. Perhaps more than any other film-director raised on the French New Wave – born in 1953, shooting his first short in 1973 – Moretti has been turning around the question that François Truffaut posed as a key to the seventh art: is cinema more important than life? But where for Truffaut, or Rossellini, as for many amongst their long and glorious lineage (from Spielberg to Tran Anh Hung) the dilemma has been between a painful reality full of obstacles on one side and a ‘harmonious’ path where ‘there are no traffic jams’ (to speak like Truffaut in his 1973 Day for Night), on the other – in other words, where cinema is the path of escape towards a world where dreams (or nightmares) come true – for Moretti, it is the dilemma itself which is the essence of cinema.

Nanni Moretti has always been a melancholic in denial. Perhaps more than any other film-director raised on the French New Wave – born in 1953, shooting his first short in 1973 – Moretti has been turning around the question that François Truffaut posed as a key to the seventh art: is cinema more important than life? But where for Truffaut, or Rossellini, as for many amongst their long and glorious lineage (from Spielberg to Tran Anh Hung) the dilemma has been between a painful reality full of obstacles on one side and a ‘harmonious’ path where ‘there are no traffic jams’ (to speak like Truffaut in his 1973 Day for Night), on the other – in other words, where cinema is the path of escape towards a world where dreams (or nightmares) come true – for Moretti, it is the dilemma itself which is the essence of cinema.

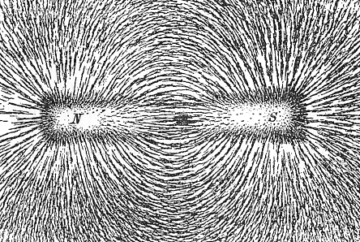

I never heard Henry Bull, my father-in-law, claim he invented the Whee-Lo, but his proud sons have on occasion. He manufactured and distributed the toy, and made it into a nationwide sensation in 1953, just before the hula hoop and Frisbee. A curved double metal track that held a spinning plastic wheel, the gyroscopic magnetic Whee-Lo is still available for purchase, most frequently at airport gift shops. By flicking your wrist, you propel the wheel and its spinning progress down the track and back. Mesmerizing, it’s a sort of fifties’ analog Game Boy. First called the Magnetic Walking Wheel, it came packaged with six colorful cardboard discs known as “Whee-lets” that created optical illusions as the wheel spun. According to Fortune, Henry’s company, Maggie Magnetics, sold two million units its first year.

I never heard Henry Bull, my father-in-law, claim he invented the Whee-Lo, but his proud sons have on occasion. He manufactured and distributed the toy, and made it into a nationwide sensation in 1953, just before the hula hoop and Frisbee. A curved double metal track that held a spinning plastic wheel, the gyroscopic magnetic Whee-Lo is still available for purchase, most frequently at airport gift shops. By flicking your wrist, you propel the wheel and its spinning progress down the track and back. Mesmerizing, it’s a sort of fifties’ analog Game Boy. First called the Magnetic Walking Wheel, it came packaged with six colorful cardboard discs known as “Whee-lets” that created optical illusions as the wheel spun. According to Fortune, Henry’s company, Maggie Magnetics, sold two million units its first year.