by Michael Liss

It has become a disturbing feature of some recent opinions to criticize the decisions with which they disagree as going beyond the proper role of the judiciary. …[W]e do not mistake this plainly heartfelt disagreement for disparagement. It is important that the public not be misled either. Any such misperception would be harmful to this institution and our country. —Chief Justice John Roberts, Opinion of the Court, Biden v. Nebraska

Let us not be misled.

Here we go again. Another year, another round of controversial Supreme Court rulings, another set of difficult questions about the behavior of Supreme Court Justices.

This is not a happy group, and the unhappiness is not merely ideological. The personalities are different. In each of the four instances of changing seats since 2016, the Court lost a bit of its temperamental cohesiveness. Beyond the famous friendship between Justices Scalia and Ginsburg, Justice Kennedy was conciliatory and mindful of the Court’s traditions; Justice Breyer was courtly and insisted he was among friends. Now we have Justice Kagan squaring off against the Chief; Justices Thomas and Jackson engaging in what looks to be a very personal argument; and Justice Alito veering from searching for the Dobbs leaker, to accusing his critics of endangering his life, to airing his grievances from the safe space of the WSJ Opinion pages. Let me admit to being surprised that Justice Kavanaugh not only vouches for collegiality, but is also the Justice most in the majority.

That the liberal wing of the Court is discontented is understandable—with a couple of exceptions, it’s getting crushed on the field. Linda Greenhouse, in an article for The New York Times, points out that long-held conservative wishes that had been dammed up behind the pre-Trump-largely-centrist Court have been realized. Abortion, guns, affirmative action, the open embrace of religion, and a heavy SCOTUS hand on those regulatory actions of which conservatives don’t approve—all these trophy wins have been banked, with more to come. Greenhouse ends on what anyone who believes in checks and balances should find chilling: “The Supreme Court now is this country’s ultimate political prize.” Read more »

Maria Berrio. From the series “In A Time of Drought”.

Maria Berrio. From the series “In A Time of Drought”. The Lede

The Lede 1.

1.

“D — — , I presume, is not altogether a fool, and, if not, must have anticipated these waylayings, as a matter of course.”

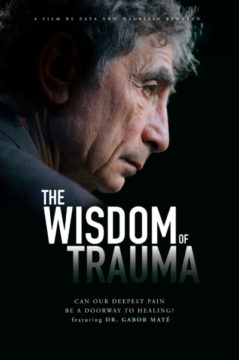

“D — — , I presume, is not altogether a fool, and, if not, must have anticipated these waylayings, as a matter of course.” He received the Order of Canada, profoundly helped many people with addiction on the streets of Vancouver, and is much loved and admired, but some of Dr. Gabor Maté’s claims feel like they don’t hold water. And some claims might actually be dangerous if blindly accepted.

He received the Order of Canada, profoundly helped many people with addiction on the streets of Vancouver, and is much loved and admired, but some of Dr. Gabor Maté’s claims feel like they don’t hold water. And some claims might actually be dangerous if blindly accepted.

Boomer-bashing is everywhere. Maybe it’s warranted, but a reality check is in order, because the bashing starts from an easy and false idea about how power has moved in American society. The recent change in House Democratic leadership is almost too perfect an example. As a “new generation” takes power in the top three offices, we quietly ignore the most interesting generational story. We griped about the old guard clinging to power, and we cheer for our new young leaders, but we don’t mention that political power skipped a generation: it passed from the pre-Baby Boom generation to the post-Baby Boom generation. The Boomers themselves were shut out of power. As usual.

Boomer-bashing is everywhere. Maybe it’s warranted, but a reality check is in order, because the bashing starts from an easy and false idea about how power has moved in American society. The recent change in House Democratic leadership is almost too perfect an example. As a “new generation” takes power in the top three offices, we quietly ignore the most interesting generational story. We griped about the old guard clinging to power, and we cheer for our new young leaders, but we don’t mention that political power skipped a generation: it passed from the pre-Baby Boom generation to the post-Baby Boom generation. The Boomers themselves were shut out of power. As usual.