by Michael Liss

Nearly 250 years is not quite Shakespeare, but if The Wealth of Nations were a play, we would say it has had a pretty good run. Is it a dusty old warhorse, to be read while sitting in a winged-back chair with a snifter of brandy, or still relevant today? Can it solve the (deep) problems of the present and future? Is our almost faith-bound devotion to market forces still justified, or are new approaches needed?

A heavy topic requires heavyweights, and I found them at this past November’s “Center on Capitalism and Society,” at Columbia University’s 20th Anniversary Conference. The topic: Economy Policy and Economic Theory for the Future

The two-day event assembled a formidable crew of speakers, headlined by three Nobelists for Economics: Joseph Stiglitz (2001), Eric Maskin (2007) and Edmund Phelps (2006). They were joined by a “supporting cast” of 15 others, also heavyweights in their field, including the sociologist and urbanist Richard Sennett, the financial journalist Martin Wolf, Finnish philosopher Esa Saarinen, Ian Goldin of Oxford, economists Roman Frydman and Jean-Paul Fitoussi, Carmen Reinhart of the World Bank, and Jeffrey Sachs of Columbia and the UN.

In short, there were a lot of credentials in the room (either in person or remotely) and a number of extremely compelling presentations, but it is Sachs whom I want to talk about. He spoke first, after opening remarks by the extraordinary Ned Phelps (nearing 90, still writing, still speaking, and still mentoring and inspiring), and I assume that the choice was a tactical one. The organizers clearly anticipated that Sachs would do what Sachs does: devote his time to lobbing a little hand grenade into the proceedings: Capitalism, to his way of thinking, particularly the Anglo-Saxon version of Capitalism practiced in the United States, was no longer capable of taking on the big, global challenges.

Sachs has an interesting affect. I have included a YouTube link to his talk (The Center has uploaded links to all the presentations), and it really is worth watching, but pay attention. He has a bit of a Midwestern accent, he’s very low key, and his voice is carefully modulated, yet he moves like a big tight end with an unusually fast first step—sleep on him and you won’t catch up. Of course, it’s his content that matters, what happens after he takes that first step, and that content leaves a lot of people with a lot to disagree with.

What Sachs does really well is challenge people, not merely with his ideas, but also because some of his answers dissatisfy them so much they refuse to give a fair hearing to his questions.

So, if you are a good American capitalist, devoutly believe that our system as it presently exists is, for now and forever, the best way of solving every problem, I’d recommend Sachs even more. This is not an attempt to convince you Sachs’ Elixir is the cure-all (I’m enough of a good capitalist myself to doubt that). It is to ask you if his questions have any validity whatsoever, and, if they do, how we good capitalists expect to solve them.

Sachs identifies six issues as what he terms Fundamental Drivers Of Systemic Change: The Anthropocene, Geopolitics, Demographic Disruption, Efficacy of Social Democracy, Smart Machines and Digital Society, and Wealth and Wellbeing. Then he offers five emerging institutional priorities and ethical emphases: (1) Social democratic distribution of services, (2) Global fiscal/financial regime of tax sharing and redistribution, (3) Public planning and investment of sustainable architecture, (4) Rise of leisure and care economy, and (5) Preeminent role of open-source public science and industrial policy.

It is fair to say that not everyone will acknowledge that all six of Sachs’s Fundamental Drivers in fact, represent problems. Some may even regard aspects of one or more of them as actually desirable. Even fewer will go along with his solutions. Sachs says that if you want to see the future, it’s Norway, which is not a line you are likely to hear quoted with approval at, say, the Republican National Convention.

If that is the way you feel about any one of Sachs’s drivers or emerging priorities, I would really suggest you move off it and engage on the next one. We don’t have to agree with all of Sachs’s Theses to ask whether the solutions we are currently applying (or not applying) are up to the job.

Start with climate change. If you are willing to stay in for the discussion, ask yourself what Capitalism has offered. The Sachs plan is top-down, multinational coordination, with a substantial component of regulation over industry and the usage of fossil fuels. That is a heavy hand, not an invisible one. I’m skeptical, and not necessarily because of faith in markets or that I think governments always screw things up. Rather, I’m skeptical that any global solution to climate change can include the United States. Here, policy is made through a political and legislative process that, at least for now, is beholden to reflexive partisanship, the polluters, and the politicians who answer to them. If you want America truly to join in a global effort and stay in it, you have to win enough elections consecutively to make certain those policies aren’t erased after the next cycle.

That being said, I’d take even a pallid response by government over what the markets have accomplished…which is basically nothing. Here, Sachs is clearly right—the Invisible Hand is quite invisible (or, to be more cynical, the Invisible Hand is supporting profits over the public good). If America either can’t or won’t, the rest of the world may have to go its own way. Of course, there is a price for that, not just in reduction of efficacy, but also in a reduction in American influence. If we won’t play, we won’t get to make any of the rules.

Geopolitical Change: Sachs sees us approaching the end of an American-led world, and the beginning of a new era of uncertainty in which we will be lucky to escape an incredibly destructive war. Since the end of World War II, we have been the only superpower. That is no longer true, and not merely because of an emergent China. In some respects, this is inevitable—you can’t expect a country with roughly four percent of the world’s population to dominate the rest. But this presages something that will have an effect that might be beyond accurate modeling. For more than the last two centuries, the British and the American Empires have been central in defining and maintaining world order. If that center no longer holds, no one really knows what the end results might be. It might be Sachs’s Northern European paradise…or it could just as easily turn a lot more Hobbesian. By contrast, the American-led world did not always reflect the better angels of our natures, but it was often benign. Can Capitalism slow that decline, or mitigate its worst impulses? Will it be seen as relevant in another generation?

Demographic Change: We can see it all around us if we just care to look. Birth rates in developed countries have dropped below replacement rates, while those in developing countries have skyrocketed. People are moving to cities in astronomical numbers—three billion are expected in the next 30 years, vastly outpacing those city’s capacities to create and maintain infrastructure. This is all coming at a time when we have a rapidly aging population, with citizens who are moving from the productive phases of their lives to a period where their needs will sharply increase. American-style Capitalism has accepted (sometimes grudgingly) basic support for the elderly such as Social Security and Medicare, but has rejected, time and again, any efforts to expand on that. As needs inevitably increase, is this a viable approach?

Efficacy of social democracy: It is becoming increasingly clear that America, in its approach to allocation of resources and how they are applied to basic services like education, childcare and healthcare, is becoming an outlier. The countries with the resources are embracing the Northern European model and that model educates and cares for its citizens far better than we do. Sachs is right when he emphasizes a particular feature of Anglo-Saxon Capitalism…it’s astringent. Its near-Calvinism often leads to the conclusion that society owes little to its inhabitants beyond an opportunity to participate/compete in the economic system. That is the system we live in right now, and what we haven’t seen yet is a turn, at the ballot box, towards a more Progressive version of it. Our distinct preference for individualism can be a strength when we resist the stifling aspects of institutionalism, but, particularly when mixed with tribalism, is increasingly leading us off a cliff. Is our form of Capitalism really best serving the needs of the greatest number of people?

Speed Of Disruption from Machines and Technologies: Sachs recognizes one part of the problem—the massive social dislocation that will result from the destruction by technologies of millions of jobs. His solutions are interesting—more leisure time, shorter workweeks, and more resources available for the displaced so they do not need to jump into a low-paying job. But he doesn’t say how this transformation could occur, only that it should occur. In the United States, profits flow to the entrepreneurs (proportionally or disproportionately depending on your perspective). This fosters two different dynamics. First, there’s an economic one, in which a great many people who previously had comparatively good-paying jobs are being forced into lower-paying ones with less security. Second, this group doesn’t turn to those who offer a more communitarian response—rather, the dislocated align themselves with the cultural populism of the autocratic right. In a political culture in which one is accused of being a Communist by someone taking government payments so they can avoid an employer mandate to get vaccinated, it is very hard to see how we can achieve what Sachs calls an “equitable allocation.” That being said, our brand of Capitalism doesn’t seem to be providing good new jobs as quickly as old ones are being killed off. So, while you might reasonably argue that Sachs is wrong, relying on a “markets will provide” mantra when they aren’t also seems to be a leap of faith.

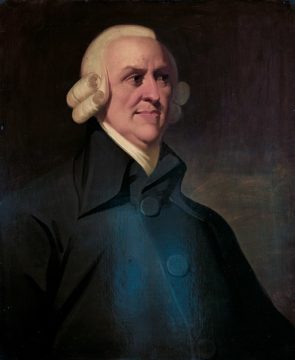

Wealth and Wellbeing: Sachs allows that the central promise of Adam Smith’s Capitalism, that it would lift the many out of poverty, was, in large part, met. But he feels it no longer seems to be delivering in the same way. He wants a new orientation in which entrepreneurship is less glamorized and community more emphasized. He notes that many great scientific advances are not always the product of markets, but instead of great learning and research institutions. An interconnected world, to Sachs’s way of thinking, is one that can cooperate in addressing the existential issues that face us. It can play a central role in planning and developing basic and sustainable infrastructure—including the energy system. It can reduce the competition among countries for capital and induce more sharing of resources. Finally, it can foster, here in the United States, a change of culture, so that the delivery of basic social services is recognized as a human right, lifting many out of despair.

Sachs can seem so out there on some solutions, but, to return to my starting point, is he really wrong on the issues that plague us and the world? You may not believe his ideas are good ones, you may think that Capitalism would do it better, but has it done it better? Doesn’t it need to do better, or to outsource the things it is unsuited for?

I think it does. A Washington Post-University of Maryland poll released this past weekend indicates that 34 percent of Americans say violent action against the government is justified at times. Yes, some of that anger and bloodlust is a result of politicians playing with fire in order to satisfy their ambitions. But could it really take root in a society that was solving problems and successfully providing basic necessities and opportunities for as much of the population as possible? Economic insecurity leads to radicalization and an emphasis on hormonal issues. Once a fire starts, it can burn down an entire town—including the gated communities.

So, if we don’t want the barbarians outside those gates, perhaps it is time to think anew. It doesn’t have to be the Jeff Sachs way: Adam Smith himself might think that the market for innovative ideas is ripe for those who are willing to take risks. The Invisible Hand need not be the Dead Hand.