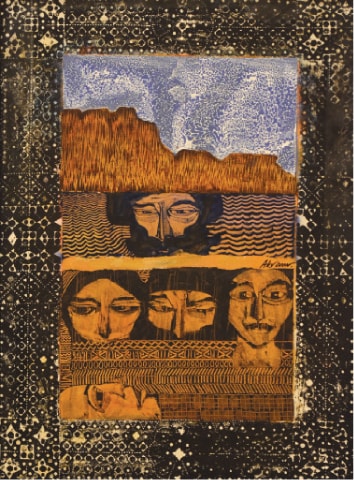

Akram Dost Baloch. From the exhibition “Identities”, 2020.

Akram Dost Baloch. From the exhibition “Identities”, 2020.

Staying Alive: The Owl, the Orca, and the Human Problem

by David Greer

The northern spotted owl (Strix occidentalis caurina) and the southern resident orca (Orcinus orca) are dramatically different animals that employ curiously similar predation techniques, and both face extinction thanks in large part to their choice of prey.

The northern spotted owl, one of three subspecies of spotted owls, is slightly smaller than a raven and inhabits mature forests along the Pacific coast of North America from southwestern British Columbia to northern California. The southern resident orca, sometimes called the killer whale, occupies the same part of the world and is found primarily in the coastal waters of British Columbia, Washington and Oregon, and most especially throughout the Salish Sea.

Though the extinction threats they face are different in nature, there is one very similar root cause—the fact that they are both fussy eaters.

The diet of the spotted owl consists primarily of two small rodents: bushy-tailed wood rats (otherwise known as pack rats) and flying squirrels. Like most other owls, the spotted owl hunts primarily in the dark. To catch its prey efficiently with minimal expenditure of energy, it has evolved two remarkable and complementary aptitudes: exquisite hearing and silent flight. Unlike some owl species that prowl at night in search of prey, the spotted owl simply perches in a tree, waits motionless, and intently listens. If it hears the scratching of pack rat toenails on a log or the soft impact of a flying squirrel landing on a tree trunk, it unfolds its wings and launches towards the sound. Like other owls, the spotted owl has evolved a structure and texture of feathers that ensures an almost soundless flight. Read more »

Losing

by Eric Bies

There may be no concept so alluring in all of science fiction than that of time travel. We are undoubtedly drawn to alien species and places in space—moons to colonize, asteroids to mine. But even freakish beings and far-off worlds, however remote, have always smacked a little too much of our own reality. I’m fully capable, after all, of walking from my apartment to the park. I can sit on a bench and read National Geographic. What I can’t do (and have an immensely difficult time imagining ever being able to do, so that the notion borders on fantasy) is step outside and arrive at yesterday.

There may be no concept so alluring in all of science fiction than that of time travel. We are undoubtedly drawn to alien species and places in space—moons to colonize, asteroids to mine. But even freakish beings and far-off worlds, however remote, have always smacked a little too much of our own reality. I’m fully capable, after all, of walking from my apartment to the park. I can sit on a bench and read National Geographic. What I can’t do (and have an immensely difficult time imagining ever being able to do, so that the notion borders on fantasy) is step outside and arrive at yesterday.

And yet how many of us wish we could!

The more melancholy among us, given to regret, get stuck in the mud of wishing just that. (And the reasons, from finance to romance, could occupy an entire essay of their own.) But how many of us at the same time wish to know, for the sheer fun of finding out, whether Jesus Christ had curly hair or straight? (My bet is he was bald.) Yes, who else but we the hopelessly curious can be depended on to investigate, if one day someone does invent a time machine, who Jack the Ripper was, whether there ever was a warrior-king called Odysseus, and what Cleopatra and T-Rexes really looked like?

Here’s another mission: Go back to 1880, clap a beard on your face, stump down to the British Library, and ask one of the assistants to judge whether the name of John Ruskin, the most eminent English writer then living, will remain recognizable to readers in the year 2020. Of course, this is something like surmising today Brad Pitt’s popularity in 2160: if we wish to know, it’s because we can’t, and so we ask: Does one future grow any less certain the more certain than others it seems? Is there some universal law that invites expectation only to subvert it? Read more »

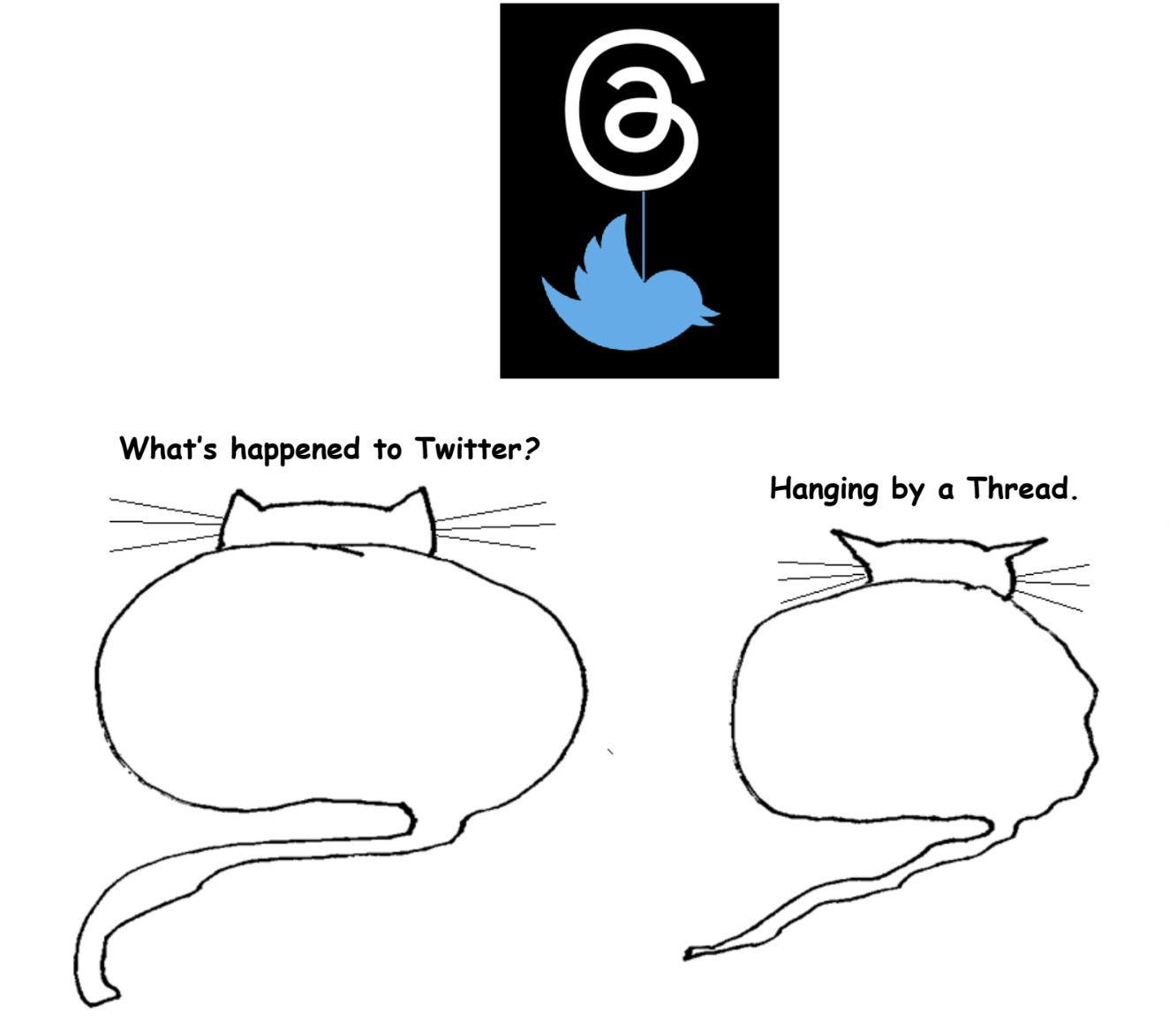

Catspeak

by Brooks Riley

Translation as Colonialism’s Engine Fuel in R. F. Kuang’s Babel

by Claire Chambers

Rebecca F. Kuang’s new novel Yellowface, a hilarious and haunting satire about the publishing industry, is proving a literary fiction bestseller this summer. However, it is her previous book Babel, or the Necessity of Violence that interests me here. Whereas Yellowface concerns contemporary America, Babel is a capacious piece of speculative fiction mostly set in Oxford during the 1830s. It was published in the Covid-19 pandemic under the young author’s abbreviated first name, and was a surprise hit due in part to its popularity on BookTok. As I will discuss, the novel deals with issues of language, translation, and colonialism in a startlingly original way.

Rebecca F. Kuang’s new novel Yellowface, a hilarious and haunting satire about the publishing industry, is proving a literary fiction bestseller this summer. However, it is her previous book Babel, or the Necessity of Violence that interests me here. Whereas Yellowface concerns contemporary America, Babel is a capacious piece of speculative fiction mostly set in Oxford during the 1830s. It was published in the Covid-19 pandemic under the young author’s abbreviated first name, and was a surprise hit due in part to its popularity on BookTok. As I will discuss, the novel deals with issues of language, translation, and colonialism in a startlingly original way.

Protagonist Robin Swift had been born in Canton and given a Chinese name that is never disclosed. After his mother’s death in the so-called Asiatic Cholera pandemic of the late 1820s, a professor called Richard Lovell becomes his guardian for reasons initially unknown. Lovell allows the boy to choose his own name (he decides on ‘Robin’ for the bird, and ‘Swift’ from Gulliver’s Travels) before bringing him to England.

Lovell prepares Robin for admission at the prestigious Royal Institute of Translation at Oxford, known to students as Babel. Compared with the classist and white supremacist patriarchy of the rest of Oxford University in that period at least, Babel is multilingual, multicultural, and even admits girls. Here Robin makes three friends: Ramy from Calcutta, Haitian Victoire, and the English rose Letty. In the institute’s intensive language programme, the teenagers’ friendship too quickly becomes intense. Ramy, Victoire, and Robin still feel a complex loyalty to the (quasi-)colonized homelands they had to leave behind. Cracks start to emerge in their relationship with Letty, who holds sympathy for the British civilizing mission. Read more »

To Create is to be Free

by Ed Simon

I am condemned to be free. —Jean-Paul Sartre, Being and Nothingness

Well, I wish I could be like a bird in the sky,

how sweet it would be if I found I could fly,

Oh, I’d soar to the sun and look down at the sea,

and then I’d sing ’cause I’d know, yeah,

I’d know how it feels

I’d know how it feels to be free. —Nina Simone, “I Wish I Knew How to be Free”

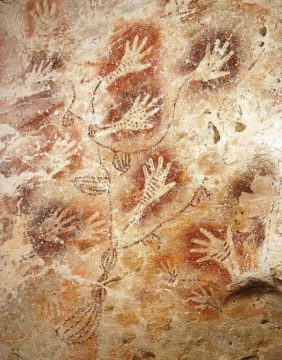

First mixing the grounds of red and yellow ocher with water so as to make a viscus, sticky gum which she puts between her cheek and whatever teeth she may have had, the woman placed her rough, calloused, weather-beaten, sun-chapped hand against the nubbly surface of the limestone cave’s wall, and then perhaps using a hollow-reed picked from the silty banks of the Rammang-rammang River she would blow that inky substance through her straw, leaving the shadow of a perfect outline. This happened around forty thousand years ago and her hand is still there. A little over two dozen of these tracings in white and red are all over the cave wall. What she looked like, where she was born, whether she had a partner or children, what gods she prayed to and what she requested will forever be unknown, but her fingers are slim and tapered and impossible to distinguish from those of any modern human. “It may seem something of a gamble to try to get close to the thought processes that guided these people,” writes archeologist Jean Clottes in What is Paleolithic Art?: Cave Paintings and the Dawn of Human Creativity. “They are so remote from us.” Today a ladder must be pushed against the surface of the cave’s exterior, which appears as if a dark mouth over the humid, muddy Indonesian rice fields of South Sulawesi Island, so as to climb inside and examine her compositions, but during the Neolithic perhaps they simply cleaved alongside the rock face with their hands and feet. Several other paintings are in the complex; among the earliest figurative compositions ever rendered, some of the sleek, aquiline, red hog deer, others of chimerical therianthropes that are part human and part animal. Beautiful, obviously, and evocative, enigmatic, enchanting, but those handprints are mysterious and moving in a different way, a tangible statement of identity, of a woman who despite the enormity of all of that which we can never understand about her, still made this piece forty millennia ago that let us know she was here, that she lived. Read more »

First mixing the grounds of red and yellow ocher with water so as to make a viscus, sticky gum which she puts between her cheek and whatever teeth she may have had, the woman placed her rough, calloused, weather-beaten, sun-chapped hand against the nubbly surface of the limestone cave’s wall, and then perhaps using a hollow-reed picked from the silty banks of the Rammang-rammang River she would blow that inky substance through her straw, leaving the shadow of a perfect outline. This happened around forty thousand years ago and her hand is still there. A little over two dozen of these tracings in white and red are all over the cave wall. What she looked like, where she was born, whether she had a partner or children, what gods she prayed to and what she requested will forever be unknown, but her fingers are slim and tapered and impossible to distinguish from those of any modern human. “It may seem something of a gamble to try to get close to the thought processes that guided these people,” writes archeologist Jean Clottes in What is Paleolithic Art?: Cave Paintings and the Dawn of Human Creativity. “They are so remote from us.” Today a ladder must be pushed against the surface of the cave’s exterior, which appears as if a dark mouth over the humid, muddy Indonesian rice fields of South Sulawesi Island, so as to climb inside and examine her compositions, but during the Neolithic perhaps they simply cleaved alongside the rock face with their hands and feet. Several other paintings are in the complex; among the earliest figurative compositions ever rendered, some of the sleek, aquiline, red hog deer, others of chimerical therianthropes that are part human and part animal. Beautiful, obviously, and evocative, enigmatic, enchanting, but those handprints are mysterious and moving in a different way, a tangible statement of identity, of a woman who despite the enormity of all of that which we can never understand about her, still made this piece forty millennia ago that let us know she was here, that she lived. Read more »

Monday Photo

My wife and her mother walking in the mountains near Meransen, South Tyrol.

Gender Existentialism

by Ethan Seavey

“Man is born free and everywhere he is in chains.” —Jean-Jacques Rousseau (some guy who wound up as the father of French philosophy)

How much you can divide this sentence into similarly incorrect phrases?

How much you can divide this sentence into similarly incorrect phrases?

[Man is born free and everywhere he is.] “Everywhere” is incorrect because the idea of a man is extremely limited to the societal sphere in which he lives. The American white man is gendered so differently from the French white man. The American white man is also different from his neighbor who is Black, his neighbor who is gay, and his neighbor who is white but born into poverty. They are all Men and they experience that differently. Any attempt to define what a man is by social attributes alone is futile because it will always exclude people who identify as men.

[Man is born free] is incorrect because they are subjected to forces more powerful than them which force them into labor and strip freedoms.

[Man is born] is incorrect because Man is made. Consider: a baby is born into a world. A doctor inspects the baby’s genitalia. The doctor decides which sex the baby will be labeled. In some cases, the doctor will modify the baby’s body to ensure that they will fit into one of two options. Then the baby is not a baby. He is a baby boy; she is a baby girl. In that order. He is a To-Be-Man; she is a To-Be-Woman. The troubling part is that every person is labeled a To-Be-Something before they have the opportunity to decide what they are, or what that even means for them.

The position of being a Young Man or a Young Woman may be the first time that the person has the opportunity for choice. With the independence to explore their connection to their gender for the first time, it can be exciting. For cisgender, heterosexual people, it’s a euphoric moment of being recognized as you truly want to be.

For queer people, this euphoria does not come with being recognized as a Man or Woman. The very opposite is true, leading to what I’d call Gender Insecurity. In my own experience, I found that Gender Insecurity transformed into two different manifestations, fighting within myself. Read more »

Nomads and Gastronomes

by Dwight Furrow

Flavors are nomads. They lurk in disparate ingredients and journey from dish to dish. They cross generations and geographical borders putting down roots in far-flung locations, pop up when least expected, and appear in different guises depending on specific mixtures and combinations. Flavors are a molecular flow continuously reshaping each other in reciprocal determination.

The task of gastronomy is to understand this complexity. But how? As I noted in a previous post, there appears to be no global similarity space mapping relations between flavors/aromas and no rules governing how they should be combined. Are there strategies for grasping this contingency and complexity?

In general, we humans have developed two strategies for dealing with complexity. The first, macro-reduction, is of ancient lineage. We develop a taxonomy of categories into which we can neatly slip any object we encounter, carving nature at its joints, as Plato wrote. Any phenomenon can be understood as a particular instance of a general category which can then serve as a norm to judge whether the phenomenon in question is a good example of its type.

In the food world, this means we think of flavors in terms of the ingredients and dishes in which they appear, which are then grouped according to the culture from which they emerge. We divide the world of cuisine into “Italian food,” “Chinese food,” “Mexican food, etc. and these categories guide our expectations about what food should taste like. Read more »

Monday, July 3, 2023

Why I Am Not NOT a Buddhist

by Deanna K. Kreisel (Doctor Waffle)

I have a confession to make: I ❤️ Seymour Glass. If you don’t know who that is, count yourself lucky and walk away now—come back in a few weeks when I’ll be discussing humiliating experiences at middle-school dances or whatever. (Obviously I am joking—as always, I desperately want you to finish reading this essay.)

I have a confession to make: I ❤️ Seymour Glass. If you don’t know who that is, count yourself lucky and walk away now—come back in a few weeks when I’ll be discussing humiliating experiences at middle-school dances or whatever. (Obviously I am joking—as always, I desperately want you to finish reading this essay.)

For the uninitiated, Seymour was the scion of the Glass family, a half-Jewish-half-Irish troupe of tragic prodigies populating nine stories by J. D. Salinger, of Catcher in the Rye fame, set in the years 1924 to 1959. If you’re familiar with the oeuvre of Wes Anderson, you probably know that the Royal Tenenbaums are generally considered an homage to the Glasses. Both families are casually and eccentrically well-to-do, aswim in a world of brownstones, 5 p.m. martinis, private education, summers in the Hamptons, family branches in Connecticut, fur coats, and tennis lessons. And they’re all brilliant. On this point Salinger was most adamant—every child of the Glass family, all seven of them, appeared on the fictional radio program “It’s A Wise Child,” a purportedly wholesome entertainment wherein smarty-pants kids are prompted to say unintentionally hilarious smarty-pants things, but (IMO) is clearly just a wisecrack sweatshop where children are ruthlessly exploited for their youthful naïveté and left dessicated husks sucked dry of all joy.[1]

But Seymour alone is a true savant. Precocious even by Glass family standards, he is a brilliant poet who becomes a professor of English at Columbia by the age of 20. He is also the most tragic member of the gang, a real Romantic-hero type. Too smart and sensitive for the world around him, even his gifted family members,[2] he eventually blows his brains out in a Florida hotel room in front of his sleeping wife. This all happens in the very first story in which he appears, “A Perfect Day for Bananafish,” so from the moment of his introduction we already know he is doomed. Read more »

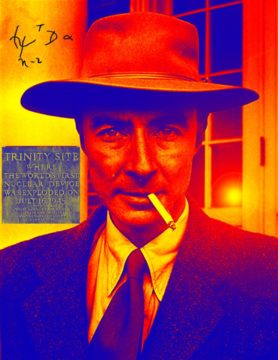

Oppenheimer VII: “Scorpions in a bottle”

by Ashutosh Jogalekar

This is the seventh in a series of essays on the life and times of J. Robert Oppenheimer. All the others can be found here.

The Bohrian paradox of the bomb – the manifestation of unlimited destructive power making future wars impossible – played into the paradoxes of Robert Oppenheimer’s life after the war. The paradox was mirrored by the paradox of the arena of political and human affairs, a very different arena from the orderly, predictable arena of physics that Oppenheimer was used to in the first act of his life. As Hans Bethe once said, one reason many scientists gravitate toward science is because unlike politics, science can actually give you right or wrong answers; in politics, an answer that may be right from one viewpoint may be wrong from another.

In the second act of his life, like Prometheus who reached too close to the sun, Oppenheimer reached too close to the centers of power and was burnt. In this act we also see a different Oppenheimer, one who could be morally inconsistent, even devious, and complicated. His past came to haunt him. The same powers of persuasion that had worked their magic on his students at Berkeley and fellow scientists at Los Alamos failed to work on army generals and zealous Washington bureaucrats. The fickle world of politics turned out to be one that the physicist with the velvet tongue wasn’t quite prepared for. Read more »

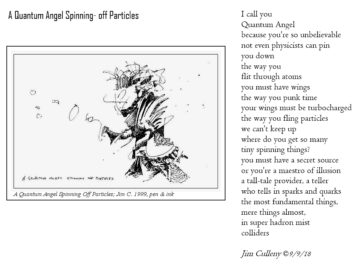

Monday Poem

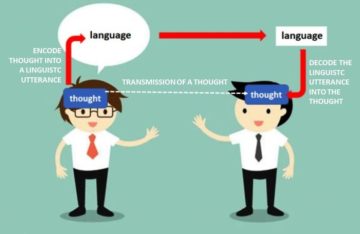

On Ambiguity and Inexplicitness in Language and Thought

by David J. Lobina

It is often stated that natural language is both ambiguous and inexplicit to be the medium of thought – to be the medium in which we think, as opposed to the conceptual language of thought I have gone on about for some time here at 3 Quarks Daily. But what do we mean when we say that language is ambiguous and inexplicit?

In the case of ambiguity, there are two relevant cases: lexical ambiguity, where a word may mean different things in different contexts (think of the word bank and all the things it can refer to); and structural ambiguity, as in the sentence below, which can receive different interpretations depending on what part of the sentence the phrase in Paris actually modifies.

The author of Stephen Hero decided to write Finnegans Wake in Paris.

That is, did the decision to write Finnegans Wake take place while the noted author was in Paris, or did the author of Stephen Hero decide that Paris would be a suitable place in which to carry out the foreseen writing? Or to put it in more linguistic terms: does the prepositional phrase in Paris modify the overall phrase decided to write Finnegans Wake or just the internal and thereby shorter phrase to write Finnegans Wake? Given the differing interpretations, such a sentence couldn’t possibly constitute an object of thought, for there is no such thing as an ambiguous thought. How could a person even have an ambiguous thought? Read more »

Living in a performative world: The Imaginary Audience and the Personal Fable

by Mark Harvey

I’ve mostly escaped the selfie photo culture, not out of some virtuous modesty, but because I generally look like a confused mouth-breathing moron in photos. So selfies are more of an indictment for me than something I want to post on Instagram. If I photographed like a Benicio del Toro or George Clooney, all bets would be off. And before I offend and get canceled by any mouth breathers, I am part of the mouth-breathing family due to a deviated septum. At full rest, I sound like one of those artificial lungs in hospitals.

I’ve mostly escaped the selfie photo culture, not out of some virtuous modesty, but because I generally look like a confused mouth-breathing moron in photos. So selfies are more of an indictment for me than something I want to post on Instagram. If I photographed like a Benicio del Toro or George Clooney, all bets would be off. And before I offend and get canceled by any mouth breathers, I am part of the mouth-breathing family due to a deviated septum. At full rest, I sound like one of those artificial lungs in hospitals.

But, my God, there are a lot of people roaming the world who are convinced their friends and followers could use just one more shot of them doing the Bon Jovi fingers on a beach in Cancun. Everywhere you go couples, individuals and families are setting up little super-model sets angling for just the right light, just the right 4” jump off the beach, and just the right expression communicating spontaneity or expensive vacations or being included with the cool crowd.

Instead of going somewhere to enjoy the locale, near or far, social media has turned millions into location scouts ever seeking a good post. Maybe that’s why Mark Zuckerberg changed the name of his company to Meta. What’s more meta than dedicating half your awareness to how you’ll look in a photo? Read more »

Perceptions

Escape from Brain Prison

by Oliver Waters

Panic about runaway artificial super-intelligence spiked recently, with doomsayers like Eliezer Yudkowsy prophesising that, if current progress continues, literally everyone on Earth will die.

Panic about runaway artificial super-intelligence spiked recently, with doomsayers like Eliezer Yudkowsy prophesising that, if current progress continues, literally everyone on Earth will die.

In a way, he’s right. Humanity will probably die out as technology progresses, but not quite in the depressing way he imagines. ‘Humanity’ after all, refers to two distinct things. The first is our biological species – homo sapiens. The second is our collective cultural existence – the beliefs, attitudes, and creations that make us truly who we are. Our biology is merely a platform for our humanities to dance upon, and it is a platform that transhumanists wish to eventually supersede.

If all goes well, we will design and build better bodies and neural systems that more seamlessly integrate with our information technologies. On this trajectory, there will be no grand dichotomy between humans and ‘Artificial General Intelligences’. All persons, whether descended from apes or designed in a lab, will be constantly upgrading their cognitive systems to be ever wiser and sturdier.

The first big step on this journey will involve scanning your brain for all relevant neural information, which would then be loaded into a synthetic brain, attached to a comfortable artificial body. Science fiction has already imagined the countless benefits of existing in such a digital, computational brain. Practical immortality is at the top of the list, given you can ‘download’ your backed-up state of mind into a new body if you happen to be hit by a train or are notoriously assassinated. Read more »

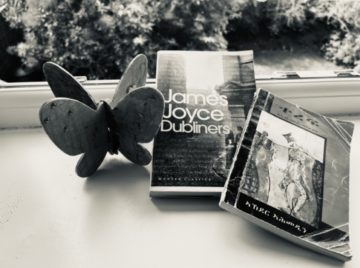

In-between Spaces and Silences : A Reading of James Joyce’s ‘Eveline’ and Akhedr Ahmedin’s ‘The Remnant’

by Muna Nassir

Sitting on the sill, head slightly resting on the pane, The Dubliners in hand, I look out the window, much like the eponymous Eveline, at the start of this particular short story. The darkness, in this case, is ready to invade not an avenue with concrete pavement and rows of redbrick terraced houses in Dublin, but an empty playground with bright coloured slides, swings, seesaws, and a roundabout in South Manchester. My vantage point allows me an eye level view of the giant oak sitting at the closest corner of the park, across the street. Unlike the slanted view from the living room, here, I can almost see the tiniest ferns sprouting on its bark. The oak’s tip points towards the sky with its thick branches spread out like the arms of a dervish in a trance. Bearing the weight of the subject in mind, I sigh in, inhaling the evening breeze. My nostrils detect not the smell of dusty cretonne but rather the scent of fallen leaves imbued with the myriad hues of autumn. From green to lime, to orange, red, maroon, and brown. The tree sits on a sideway, a space that seems to have been added as an afterthought, giving the park an irregular shape. Basking in another worldly silence, the oak exudes a stillness befitting the day’s retirement for the night. Read more »

A Respect for Old Things

by Nate Sheff

Not long ago, I went to the Yale University Art Gallery and saw their collection of Egyptian art. Seeing the dates on some of the pieces, it occurred to me that I had never really considered just how old Egyptian civilization is. I looked up some historical events to get perspective, and learned that I am closer in time to the assassination of Julius Caesar (44 BCE, which is 2,066 years ago) than Julius Caesar was to the construction of the Great Pyramid of Giza (circa 2500 BCE, over 2,400 years before Caesar’s death). Caesar’s death is ancient history, and the building of the Great Pyramid is also ancient history, but – for the sake of perspective here – the Great Pyramid’s construction was also ancient for Julius Caesar. That’s how old Egyptian civilization is.

Not long ago, I went to the Yale University Art Gallery and saw their collection of Egyptian art. Seeing the dates on some of the pieces, it occurred to me that I had never really considered just how old Egyptian civilization is. I looked up some historical events to get perspective, and learned that I am closer in time to the assassination of Julius Caesar (44 BCE, which is 2,066 years ago) than Julius Caesar was to the construction of the Great Pyramid of Giza (circa 2500 BCE, over 2,400 years before Caesar’s death). Caesar’s death is ancient history, and the building of the Great Pyramid is also ancient history, but – for the sake of perspective here – the Great Pyramid’s construction was also ancient for Julius Caesar. That’s how old Egyptian civilization is.

Four-and-a-half millennia is a long time on a human timescale, but not all timescales are human. A core sample from Methuselah, a bristlecone pine living – alive – in the White Mountains of California, shows the tree to be about 4,800-years-old. By the time they started building the Great Pyramid, Methuselah had already spent a couple centuries photosynthesizing on a mountainside, adding rings but not counting them.

Methuselah is the oldest known non-clonal tree. When we consider trees that can reproduce asexually, say, by growing new individuals from existing root systems, we find organisms like Pando, a colony of genetically-identical quaking aspens in Utah, estimated to be about 15,000-years-old. Pando had been alive for several thousand years before Göbekli Tepe, the site of the earliest known megaliths, appeared in Anatolia.

Think of how many generations of birds might have started their lives in Pando’s branches by then. Read more »

Catspeak

by Brooks Riley

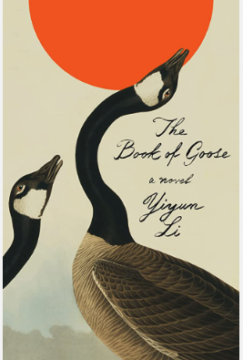

An Overabundance of Wishful Love – Yiyun Li’s “The Book of Goose”

by Varun Gauri

When Yiyun Li took questions about her new novel, The Book of Goose, at my local bookstore, someone said her new novel felt awfully dark. (I don’t remember the precise wording, though Yiyun might, as she sometimes offers people she has met briefly “a detailed account” of their encounter “out of mere mischief.”) Yiyun acknowledged the darkness, then offered an explanation — she was once a propagandist for the Chinese government, she was good at it, but now she hates propaganda, especially propaganda for life.

When Yiyun Li took questions about her new novel, The Book of Goose, at my local bookstore, someone said her new novel felt awfully dark. (I don’t remember the precise wording, though Yiyun might, as she sometimes offers people she has met briefly “a detailed account” of their encounter “out of mere mischief.”) Yiyun acknowledged the darkness, then offered an explanation — she was once a propagandist for the Chinese government, she was good at it, but now she hates propaganda, especially propaganda for life.

There was an audible gasp in the audience, then silence. I suspect many were asking themselves if they could manage without propaganda for life. In my case, I felt called out. What are A Christmas Carol, one of my favorite books, and the movie It’s a Wonderful Life, another favorite, but propaganda for life?

The Book of Goose is the story of two French farm girls, Agnès and Fabienne. Fabienne’s older sister died in childbirth, her father is a drunk, and her mother has passed away, meaning Fabienne has to tend the farm rather than attend school. Agnès’ older brother was badly wounded in the war, her sisters have gone and married, and her parents are narrow-minded and conventional. The girls, poor and lonely, already know the world is “full of nonsense.” Read more »

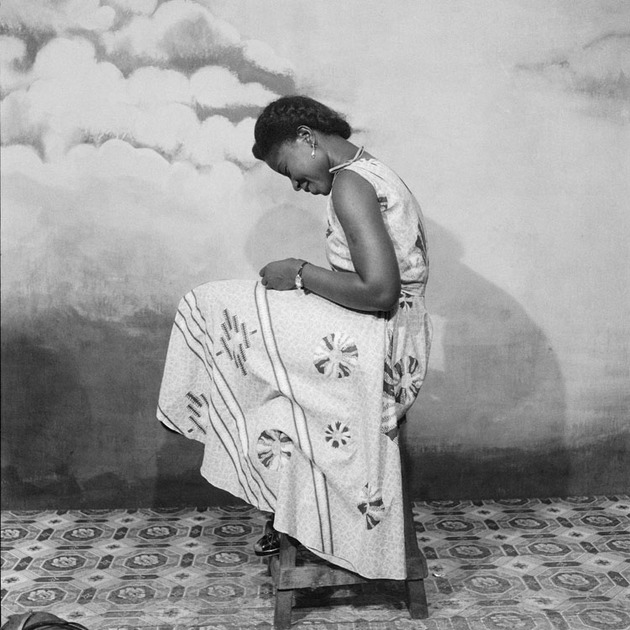

James Barnor. Portrait, Accra, ca 1954.

James Barnor. Portrait, Accra, ca 1954.