by Tim Sommers

One time, this guy handed me a picture of him and said, ‘Here’s a picture of me when I was younger.’ Every picture is of you when you were younger. – Mitch Hedberg

There’s synchronic identity, what makes you, you at a particular moment in time – say, now. And there’s diachronic identity, what makes you, you over time. For example, why are you now the same person as when you were twenty-five years old or five (if you are)? These two perspectives – synchronic and diachronic – are deeply interdependent, of course, but philosophers tend to focus on diachronic identity since what is essential to you being you is, presumably, whatever it takes for you to continue to exist. Here are some theories.

You are your soul.

The trouble with this theory is not that it usually has a religious basis. That might be trouble later, but initially the trouble is that it is not very helpful. I am my soul. So, what’s my soul? Is the soul some mysterious, ghostly thing or a Platonic form or is it just whatever is essential to who I am? If the answer is that the soul is whatever is essential to who I am, this seems like just a restatement of the question.

Keep in mind, the great innovation of Christianity was not the soul, an idea that’s been around at least since Plato and Aristotle (who thought we had three souls). The Christian innovation was bodily resurrection.

You are your ego.

The ego may just be the secular soul. Descartes’ version of the ego theory, the most influential, is that a person is a persisting, purely mental, thing. But like the soul it’s hard to unpack the ego in an informative way. It is whatever unifies our consciousness. We survive as the continued existence of a particular subject of experiences, and that explains the unity of a person’s life, i.e., the fact that all the experiences in this life are had by the same person. This is circular, of course. Further, on this view, what happens if I fall into a dreamless sleep? Or get hit on the head and black out? Go in and out of a coma? Am fully anesthetized? When I wake up and start having experiences again, how do I know I am the same ego? How do I know that the ego is a persistent thing at all? Later, we will see what Hume has to say about this.

In the meantime, we are going to need a better theory of the ego or soul before either is going to be useful as a theory of personal identity. Read more »

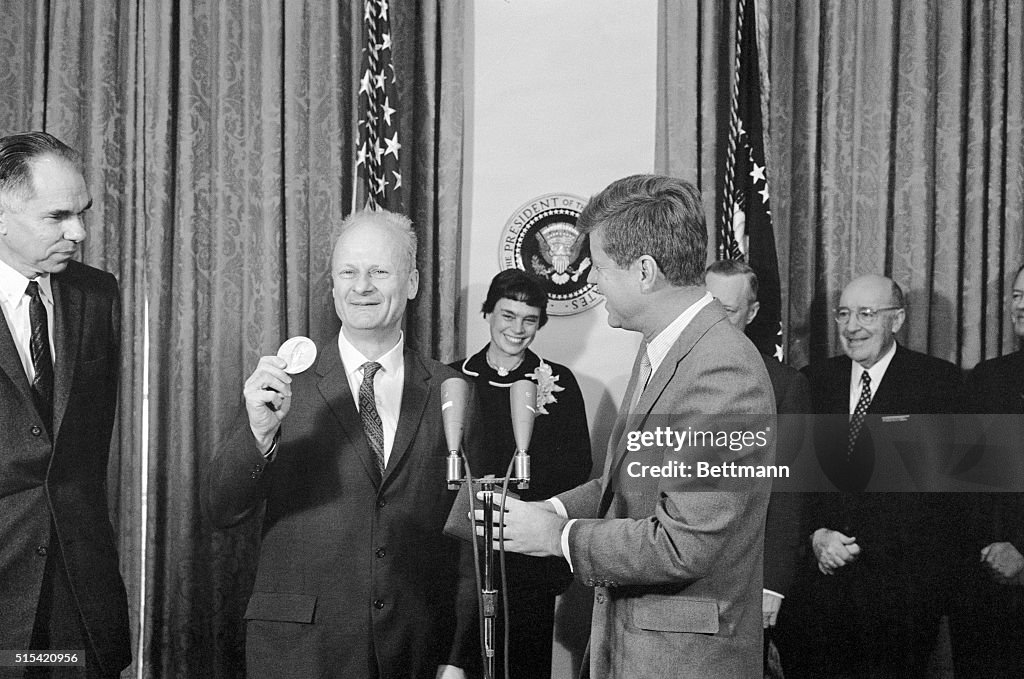

In 2016,

In 2016,

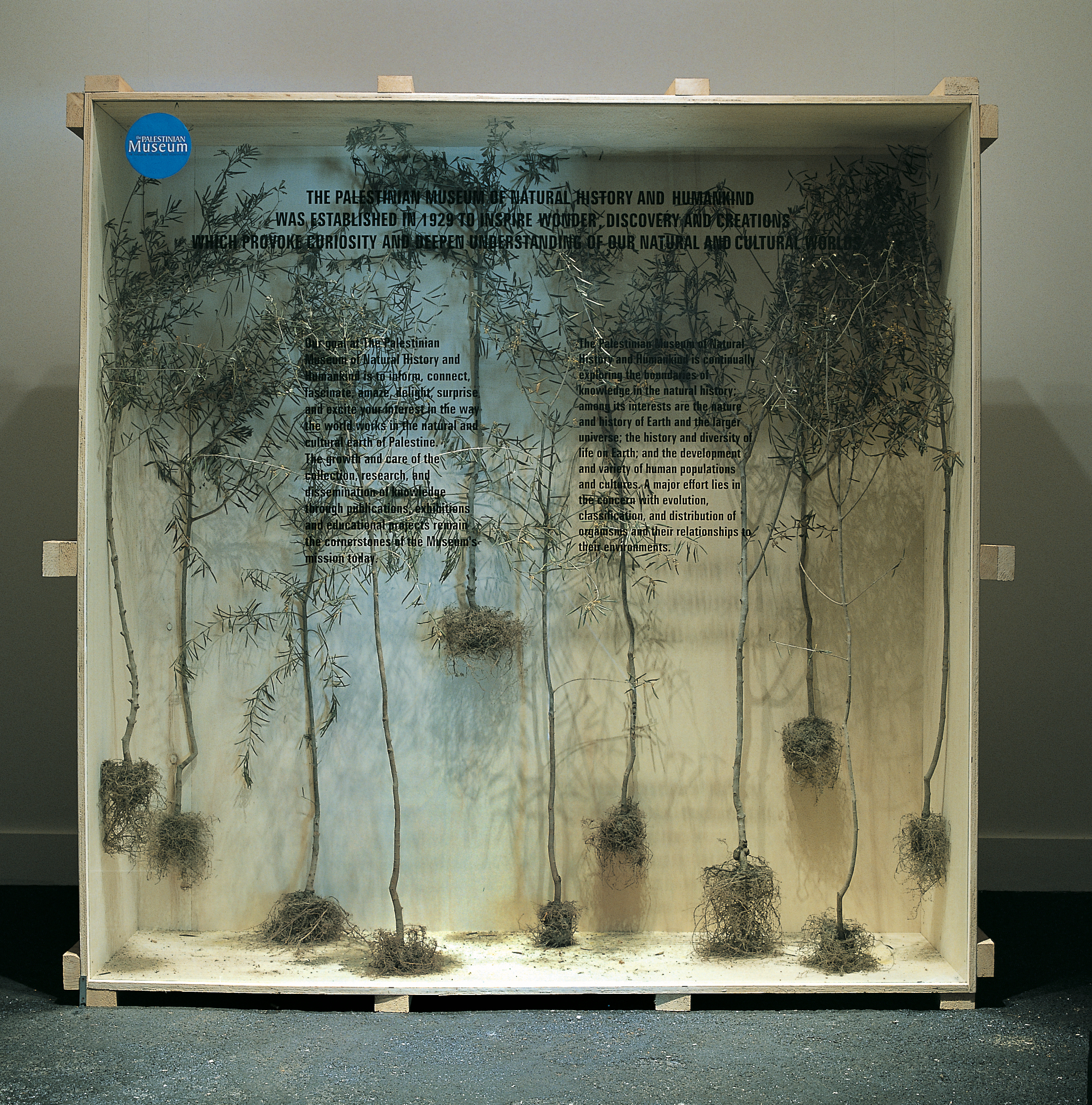

Khalil Rabah. About The Museum, 2004.

Khalil Rabah. About The Museum, 2004.

If a city could be an organism, then Kherson in Eastern Ukraine would be a sick body. For eight months, between March and November 2022, Kherson was occupied by Russian forces. Kidnapping, torture, and murder – in terms of violence and cruelty, Kherson’s citizens have seen it all. Today, even though liberated, the port city on the Dnieper River and the Black Sea is still being regularly bombarded: a children’s hospital, a bus stop, a supermarket. Even though freed, how could this city ever heal?

If a city could be an organism, then Kherson in Eastern Ukraine would be a sick body. For eight months, between March and November 2022, Kherson was occupied by Russian forces. Kidnapping, torture, and murder – in terms of violence and cruelty, Kherson’s citizens have seen it all. Today, even though liberated, the port city on the Dnieper River and the Black Sea is still being regularly bombarded: a children’s hospital, a bus stop, a supermarket. Even though freed, how could this city ever heal?

Two popular books released this year have breathed new life into the ancient debate over whether we have free will.

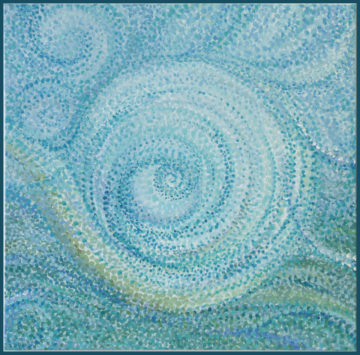

Two popular books released this year have breathed new life into the ancient debate over whether we have free will. We all naturally take an interest in the night sky. Just last week, my fiancee and I attended an event put on by the Astronomical Society of New Haven. Without a cloud in the sky, near-freezing temperatures, and a new moon, the conditions were ideal for looking through telescopes the size of cannons. To see anything, you had to stand in line, in the cold, for your opportunity to look at something for a minute.

We all naturally take an interest in the night sky. Just last week, my fiancee and I attended an event put on by the Astronomical Society of New Haven. Without a cloud in the sky, near-freezing temperatures, and a new moon, the conditions were ideal for looking through telescopes the size of cannons. To see anything, you had to stand in line, in the cold, for your opportunity to look at something for a minute.

Ron Amir. Bisharah and Anwar’s Tree, 2015. From the exhibition titled Doing Time in Holot.

Ron Amir. Bisharah and Anwar’s Tree, 2015. From the exhibition titled Doing Time in Holot.