by Richard Farr

We called my English teacher Scab for no particular reason except that it took the edge off our terror. A big man in a double breasted jacket, he wore tinted glasses that hid his expression. His head looked as if it had been carved rather carelessly from a boiled ham. “You are not going to like me,” he said to us in our first class, when I was 13. “I am the iron fist inside this institution’s velvet glove.”

It was a front, mainly. He did not suffer fools, including his pupils and most of his colleagues, at all gladly. He probably dreamed of teaching at a university, where he could have discussed Chaucer’s prosody without first getting people to stop making farting noises.

By the time I turned 17 he had softened a little, as if he could see that some of us might one day turn into bona fide human beings. And that year the national syllabus gods gifted us what was (as I gradually came to see) an absolute corker. Among other succulent morsels there were chunks of The Canterbury Tales, all of both Othello and Lear, Gulliver’s Travels, Larkin’s The Whitsun Weddings, Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, Harold Pinter’s The Birthday Party.

The most intimidating item by far was Paradise Lost Books IX and X — a hundred-score lines of theology that we found impenetrable, as if we were trying to hack our way back into an overgrown Eden long after its attendants’ banishment. Our feet tangled in the archaic vocabulary. Classical allusions stung our ignorant faces at every turn. (“Of Turnus for Lavinia disespous’d”? “Not sedulous to indite”? Both of these gems were on the first page of Book IX.) Scab spent a couple of weeks trying to make sense of it all for us but we were illiterate adolescents, lost and flailing inside an erudite adult’s poem. One day he sighed melodramatically and changed tactics. “I’ll read it to you,” he said. “Don’t think. Don’t even try to think. Just listen.”

The most intimidating item by far was Paradise Lost Books IX and X — a hundred-score lines of theology that we found impenetrable, as if we were trying to hack our way back into an overgrown Eden long after its attendants’ banishment. Our feet tangled in the archaic vocabulary. Classical allusions stung our ignorant faces at every turn. (“Of Turnus for Lavinia disespous’d”? “Not sedulous to indite”? Both of these gems were on the first page of Book IX.) Scab spent a couple of weeks trying to make sense of it all for us but we were illiterate adolescents, lost and flailing inside an erudite adult’s poem. One day he sighed melodramatically and changed tactics. “I’ll read it to you,” he said. “Don’t think. Don’t even try to think. Just listen.”

What happened next I can’t articulate with any clarity, except to say that the words melted onto his tongue like expensive chocolates, rendering his voice thick and smooth, and it was as if he had become Milton; it was as if I was present at the creation and was witnessing the poem erupt for the first time from the dark materials of the blind freedom-fighter’s imagination.

“Don’t think. Just listen.” Read more »

Shilpa Gupta. Untitled 2009.

Shilpa Gupta. Untitled 2009.

If you were a medieval peasant in the year 1323 AD, would you have believed that slavery was morally permissible?

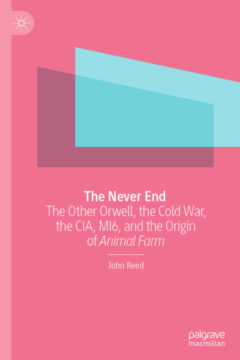

If you were a medieval peasant in the year 1323 AD, would you have believed that slavery was morally permissible? Twenty years ago, John Reed made an unexpected discovery: “If Orwell esoterica wasn’t my foremost interest, I eventually realized that, in part, it was my calling.” In the aftermath of September 11, 2001, ideas that had been germinating suddenly coalesced, and in three weeks’ time Reed penned a parody of George Orwell’s Animal Farm. The memorable pig Snowball would return from exile, bringing capitalism with him—thus updating the Cold War allegory by fifty-some years and pulling the rug out from underneath it. At the time, Reed couldn’t have anticipated the great wave of vitriol and legal challenges headed his way—or the series of skewed public debates with the likes of Christopher Hitchens. Apparently, the world wasn’t ready for a take-down of its patron saint, or a sober look at Orwell’s (and Hitchens’s) strategic turn to the right.

Twenty years ago, John Reed made an unexpected discovery: “If Orwell esoterica wasn’t my foremost interest, I eventually realized that, in part, it was my calling.” In the aftermath of September 11, 2001, ideas that had been germinating suddenly coalesced, and in three weeks’ time Reed penned a parody of George Orwell’s Animal Farm. The memorable pig Snowball would return from exile, bringing capitalism with him—thus updating the Cold War allegory by fifty-some years and pulling the rug out from underneath it. At the time, Reed couldn’t have anticipated the great wave of vitriol and legal challenges headed his way—or the series of skewed public debates with the likes of Christopher Hitchens. Apparently, the world wasn’t ready for a take-down of its patron saint, or a sober look at Orwell’s (and Hitchens’s) strategic turn to the right.

“Martti Ahtisaari, ex-Finland president and Nobel peace laureate, dies aged 86” runs the headline of

“Martti Ahtisaari, ex-Finland president and Nobel peace laureate, dies aged 86” runs the headline of

I once wrote a political column for

I once wrote a political column for

Sughra Raza. Pale Sunday Morning, April 2021.

Sughra Raza. Pale Sunday Morning, April 2021.