by Mike Bendzela

The greatest of stories has no proper beginning, at least none that we can yet discern, but proceeds from a warm, shallow shore some 375 million years ago.

There a lobe-finned fish found a way to use its bony limbs to stand up under water. It was thus able to lift its head out of the murk and gaze upon new shores that its descendants would populate.

Down through seemingly endless iterations of change, these fins were further exapted for such tasks as slogging through mud, scurrying through grass, clambering up trees, plucking fruit, scribbling letters.

The story continues on a cool, northern island, in a place called Downe, in June of the year 1858. There one of this fish’s descendants, Charles Darwin–a travel-weary, physically ill, gentleman scientist–holds in his hand an envelope addressed from the island of Ternate in Indonesia. The enclosed missive will change his world–and everyone’s–forever.

Darwin is not ready for this blow. His infant son, Charles Waring Darwin, born with Down syndrome, is not doing well: the boy is infected with the bacterium that causes scarlet fever, the same disease that killed his older sister seven years ago.

After this girl, Anne, had finally succumbed to the disease, Darwin wrote that his wife Emma and he had buried “the joy of the household,” and he settled into a long sadness.

And now it is happening again.

These catastrophes transpire while Darwin is laboring on a huge book about a simple idea he calls natural selection. For over twenty years he has solicited specimens from collectors scattered all over the world; selectively bred pigeons and orchids; sat for hours observing the behaviors of ants; boiled the flesh from rabbit carcasses and compared their bones. In the process he has accumulated thousands of pages of manuscript.

This is all done to propose a mechanism for an old idea–“the transmutation of species,” what Darwin prefers to call “descent with modification”–an idea that has not gone away in spite of scorn heaped on it by natural philosopher and clergyman alike.

The essay in Darwin’s possession has come from the hand of one of those collectors from whom he has solicited evidence. Alfred Russel Wallace is no stranger to suffering and loss. Like Darwin, he once spent four years in South America collecting massive numbers of specimens. During that time, he nearly shot off his own hand; lost his brother, Herbert, to the mosquito-borne virus that causes yellow fever; became shipwrecked in the middle of the Atlantic, losing everything he had accumulated except his diary and some sketches.

The essay he sent Darwin was written under extreme duress: Wallace had contracted malaria, another mosquito-borne plague, this time a parasitic protozoan instead of a virus. While feverish in bed, he envisioned the same mechanism for species change that Darwin had been documenting for decades.

The vision goes something like this: The profligacy of nature pits Earth’s inhabitants–a variable lot–in competition with each other continually, over resources, space, mates, hosts, status. Death is a sort of lathe that whittles from the population those unsuited for this struggle, leaving behind only those that happen to be better adapted. These survivors then pass their traits on to the next generation, and this process is repeated, nearly ad infinitum, down through the generations, over unimaginable stretches of time.

Wallace’s paper, with the unwieldy title, “On the Tendency of Varieties to Depart Indefinitely from the Original Type,” makes Darwin blanch. He realizes that this obscure collector has formulated a mechanism identical to his own. Darwin will even call their hypothesis “this child of ours.”

And now he fears Fate will snatch this latest child away from him.

Convinced his life’s work has been “forestalled,” he gives the paper to his friends Charles Lyell, author of Principles of Geology, and Joseph Hooker, Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, as Wallace has requested him to do. They come up with a plan to simultaneously credit Wallace’s originality while preserving Darwin’s precedence: They solicit from Darwin a book extract, “On the Variation of Organic Beings in a state of Nature; etc.”, and they present these men’s ideas jointly at an upcoming meeting of the Linnean Society of London and publish them side-by-side in the Society’s journal.

As these revolutionary works are being read aloud to an audience of thirty listeners, one author recovers from illness in faraway Borneo; the other attends his baby son’s burial in Downe.

Thus, on two sturdy limbs, humanity raises its head from its collective abyss of ignorance. Through them, we are permitted to gaze back, back, back upon our original selves and discover that we are not what we once thought we were.

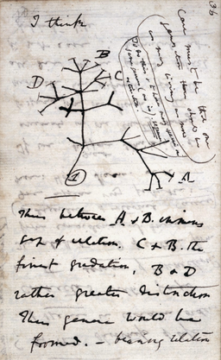

Image

Charles Darwin, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.