by Mindy Clegg

https://xkcd.com/610/

In recent years, some of the most powerful people in our society have claimed to be beleaguered outsiders. The former president is just one of the many powerful, wealthy, privileged people who declared themselves victims of a society out to destroy them and their way of life, which we’re meant to understand represents that of “real” Americans. Despite experiencing an incredibly privileged life, they claim to be the ones who are victims of jackbooted leftist thugs. There seems to be a whole cottage industry of people who rake in money by the bucketload while claiming to speak truth to the oppressive liberal/marxist power structure. They claim to be the authentic voice of the American working class, unlike the coastal elites who have no understanding of “real” life, but of course, despite their obvious privilege, they do understand the struggles of the common man. How did we get here, where men who benefit most from our social structures, position themselves as the little guy? This comes from a longer history of political shifts in America and of the rise of mass cultural consumption as a means of political expression. As culture came to stand in for political rebellion, the far right sought to weaponize mass culture to sneak in far right, reactionary ideology via the back door. But their ability to embrace an outsider status is evidence of their own privilege, as being an outsider has a strong cultural cache in our current mass mediated environment.

A contradiction rests at the heart of modernity: individualism and mass society. The enlightenment brought to the fore the concept of the individual and their role as active participants in society via citizenship. Men (mostly just men until recently) became historical agents. Alternative frameworks existed in enlightenment discourse, such as the work of people like Fredrick the Great, the Prussian ruler who advocated for enlightened despotism. Eventually, individualism won out. We can see that in the widespread adoption of John Locke’s work. He promoted the idea of the individual as the center of social and political life in a democratic society. Locke influenced the framers of the US Constitution, which would influence other constitutions around the world.1 So on the other hand was the rise of mass society under the capitalist economy in the wake of the Civil War. More goods were being mass produced and more people were embracing consumerism as a way of life. By the 20th century, mass produced goods became a means of defining one’s identity. Mass consumption reflected and shaped our culture, for good or ill. So, we are both individual actors and consumers of mass-produced goods that help define us. That contradiction opened space for both resistance and reification of capitalism. Alienation makes some easy pickings for reinforcing the worst aspects of modernity. But the more consumer choices one had access to reflected the level of privilege within that system. Those who can shape narratives in the mass media while claiming to be an outsider and often be taken at face value, are living with a great deal of privilege.

https://catandgirl.com/cat-and-girl-do-good/

Enter youth culture. Youth-oriented cultures became a cultural and political battleground.2 Out of this came youth-oriented countercultures (beatniks, hippies, punks, etc). Such countercultures did make people more aware of social alienation, but the rebellion was threaded through the consumption of mass culture. The reality is that there was no “outside the system,” only positions within the system. Often the dissent of youthful idealism gets channeled into more boutique forms of consumption rather than into political demands. Some believed it was a safer alternative to other forms of rebellion. This culture at the margins became incorporated into the mainstream culture. Thomas Frank, among others, argued that countercultural consumption were designed with that in mind.3 But political change did grow out of these highly imperfect cultural movements at times. There doesn’t really exist a perfect form of resistance, just imperfect measures for positive change. In other words, we should not completely dismiss these forms of dissent out of hand. For some, listening to challenging underground music or reading countercultural literature can open up new understandings of our Ballardian landscape of modernity. Change does begin with understanding the problem, after all.

We expect the counterculture to be a bastion of left-wing politics. However, as with movements such as MAGA, the far right has embraced a countercultural positions. During the interwar period, the far right won power during the chaos of the Great Depression. Once they gained power, and they imposed their will on everyone else. The destruction of the far right regimes at the end of the Second World War meant a need to regroup. They eventually deployed language associated with youth countercultures. In Britain in the late 1970s, the far right National Front developed a strategy of recruiting among alienated white men in the growing punk scene in the UK.4 By the 1980s, with the rise of hardcore punk in the US and Oi in the UK, violence began to be a common experience in punk spaces, and not just performative violence of the slam pit, either. Much of that violence came from skinheads, and often racist skinheads. In some scenes, violence emerged out of the divisions within the skinhead scenes, such as in Minneapolis. At the same time, the mainstream culture politicized punk via “punk panic”, driving the development of a underground.4

The ideology of the far right has become mainstream among some on the right in recent years, thanks in part to the far right’s embrace of a populist, outsider position. Despite being in the minority of the GOP, the MAGA movement led by the former President is in full control of the party. By deploying the language of racism, he earned the loyalty of underground racist groups. He also picked up support from some white, middle class Americans who likely wouldn’t join an openly racist movement, but believed themselves to be cultural outsiders despite their own privilege. MAGA is explicitly placed at odds with the “establishment” by which they mean liberals. They claim that the liberal political establishment are left-wing extremsists that operate as a conspiratorial “cabal” controlling the country at the expense of “real” Americans. Many in the MAGA movement see themselves as social rebels who are returning the country back to an idealized past (that never really existed). The term the “establishment” came to popular usage first in the British media, but it took on new dimensions in American politics. An NPR article from 2016 shows how right wing activists had started to use the term in a manner that denoted a conspiracy of the elite class—in this case within the GOP political apparatus itself. But first, this language came out of the New Left, which this article at Washington Post makes clear. The rebellion against the establishment is a fundamentally populist position, when deployed by either the left or right. The framework of the New Left rested on much firmer historical grounding than the MAGA movement of today, which pulls heavily from barely concealed bigoted tropes. They differ on solutions. The left demands more democracy and greater transparency, while the right seeks a strong man to “drain the swamp” of their perceived enemies and ensure their domination of the hated other.

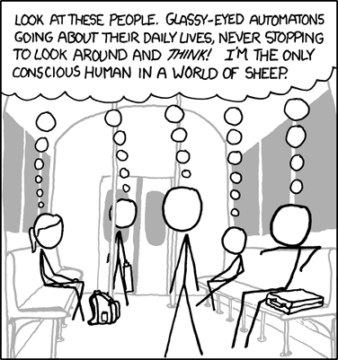

What helps to explain the embrace of violent populism of MAGA is that embrace of an outsider identity by large swaths of white, middle class Americans since the 1950s. According to historian Elizabeth Grace Hale, during the postwar era, the dominant demographic in America embraced a romanticized version of the outsider in American society. Mass culture promoted the cultural outlaw, presenting a romantic ideal of people who rejected society.5 By doing so, the most politically empowered imagined themselves as the real rebels in the American narrative. She said that it allowed “middle-class whites to cut themselves free of their own social origins and their own histories.” This was true on both the left and the right, she argued, among both the hippies and in what became the “new right” pioneered by people such as William F. Buckley.6 This was in part driven by the changes to American society in the postwar era but was understood via mass culture. It was a critique of mass culture via mass culture.7 The far right saw this as an opportunity, developing their own mass culture in the social media era. The divisions of the modern media landscape is another topic that needs its own essay, but for our purposes here we should know that Americans get their news and culture from very different places, depending on their political and social orientations. At times we don’t even understand the same facts based on our media consumption (such as who won the election 2020). The right-wing media regularly positions their viewers as the “real” outsiders in American society and that they are in an existential struggle with those who disagree with them. And that has put us into the current dangerous situation facing us. Quite frankly, as long as we keep believing in this fiction of insider-outsider dynamics, we won’t be able to see our actual shared condition within our mass mediated society. We’re all stuck here, and we can only get out if we all understand that the status quo is not working for anyone anymore.

Footnotes

1 Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, (London: Verso, 1983).

2 Jon Savage, Teenage: The Prehistory of Youth Culture, 1875-1945, (New York: Penguin Random House).

3 Thomas Frank, The Conquest of Cool: Business Culture, Counterculture, and the Rise of Hip Consumerism, (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1997).

4 Mindy Clegg, Punk Rock: Music is the Currency of Life, (Albany: SUNY Press, 2022), 83-116.

4 Robert Forbes and Eddie Stampton, The White Nationalist Skinhead Movement, UK & USA 1979-1993, (Port Townsend, WA: Feral House, 2015), 9.

5 Grace Elizabeth Hale, A Nation of Outsiders: How the White Middle Class Fell in Love with Rebellion in Postwar America, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 1.