by John Allen Paulos

Philosopher Daniel Dennett’s new book, I’ve Been Thinking, just came out, and I was reminded of a party game he’s written about. A variant of the child’s game of twenty questions, it is relevant to an increasingly pressing question: How do different social bubbles, media subcultures, or cults develop. Let me start with the game, generalized versions of which are ubiquitous. It’s probably one of Dennett’s most compelling intuition pumps; that is, thought experiments with made-up, but plausible outcomes.

Imagine a group of people at a party who choose one person and ask him (throughout, or her) to leave the room. The “victim” is told that while he is out of the room one of the other partygoers will relate a recent dream to the group. He is also told that on his return to the party, he must try, asking Yes or No questions only, to do two things: describe the dream and possibly figure out whose dream it was.

The big reveal is that no one relates any dream. The party-goers decide to respond either Yes or No to the victim’s questions according to chance or, perhaps, according to some arbitrary rule. Any rule will do and may be supplemented by a non‑contradiction requirement so that no answer directly contradicts an earlier one.

What might happen is that the victim, impelled by his own obsessions, constructs a phantasmagoric, or at least a, weird dream in response to the random answers he elicits. He may even think he knows whose dream it was, but then the trick is revealed to him. The dream, of course, has no author, but in a sense the victim himself is. His preoccupations dictate his questions, which even if answered negatively at first, frequently receive a positive response when slightly reformulated. These positive responses are then pursued. Read more »

You’ve always dreamed of foreign travel and you’re aware that there’s a long history of people doing it, and benefiting from it. But you live under a regime that closed the borders a couple of generations ago, at the same time criminalizing the act of researching potential destinations. (Many countries were dangerous, they said, and some tourists were coming home with tie-dyed shirts and peculiar ideas.) To protect the vulnerable, a War on Travel was announced. In the years since, you have grown up with little more than rumors of other cultures, climates, cuisines.

You’ve always dreamed of foreign travel and you’re aware that there’s a long history of people doing it, and benefiting from it. But you live under a regime that closed the borders a couple of generations ago, at the same time criminalizing the act of researching potential destinations. (Many countries were dangerous, they said, and some tourists were coming home with tie-dyed shirts and peculiar ideas.) To protect the vulnerable, a War on Travel was announced. In the years since, you have grown up with little more than rumors of other cultures, climates, cuisines.  Artificial intelligence – AI – is hot right now, and its hottest part may be fear of the risks it poses. Discussion of these risks has grown exponentially in recent months, much of it centered around the threat of existential risk, i.e., the risk that AI would, in the foreseeable future, supersede humanity, leading to the extinction or enslavement of humans. This apocalyptic, science fiction-like notion has had a committed constituency for a long time – epitomized in the work of researchers like

Artificial intelligence – AI – is hot right now, and its hottest part may be fear of the risks it poses. Discussion of these risks has grown exponentially in recent months, much of it centered around the threat of existential risk, i.e., the risk that AI would, in the foreseeable future, supersede humanity, leading to the extinction or enslavement of humans. This apocalyptic, science fiction-like notion has had a committed constituency for a long time – epitomized in the work of researchers like

The narrator of Alberto Moravia’s 1960 novel Boredom is constantly defining what it means to be bored. At one point, he says “Boredom is the lack of a relationship with external things” (16). He gives an example of this by explaining how boredom led to him surviving the Italian Civil War at the end of World War II. When he is called to return to his army position after the Armistice of Cassibile, he does not report to duty, as he is bored: “It was boredom, and boredom alone—that is, the impossibility of establishing contact of any kind between myself and the proclamation, between myself and my uniform, between myself and the Fascists…which saved me” (16).

The narrator of Alberto Moravia’s 1960 novel Boredom is constantly defining what it means to be bored. At one point, he says “Boredom is the lack of a relationship with external things” (16). He gives an example of this by explaining how boredom led to him surviving the Italian Civil War at the end of World War II. When he is called to return to his army position after the Armistice of Cassibile, he does not report to duty, as he is bored: “It was boredom, and boredom alone—that is, the impossibility of establishing contact of any kind between myself and the proclamation, between myself and my uniform, between myself and the Fascists…which saved me” (16). The only light in the second-class train compartment came from the moonlight, which filtered through the rusty iron grill of the window. The sun had set hours earlier, a fiery red ball swallowed whole by the famished Rajasthani countryside. I sat at the window on the bottom berth of my compartment of the Sainak Express, headed from Jaipur to Delhi.

The only light in the second-class train compartment came from the moonlight, which filtered through the rusty iron grill of the window. The sun had set hours earlier, a fiery red ball swallowed whole by the famished Rajasthani countryside. I sat at the window on the bottom berth of my compartment of the Sainak Express, headed from Jaipur to Delhi.

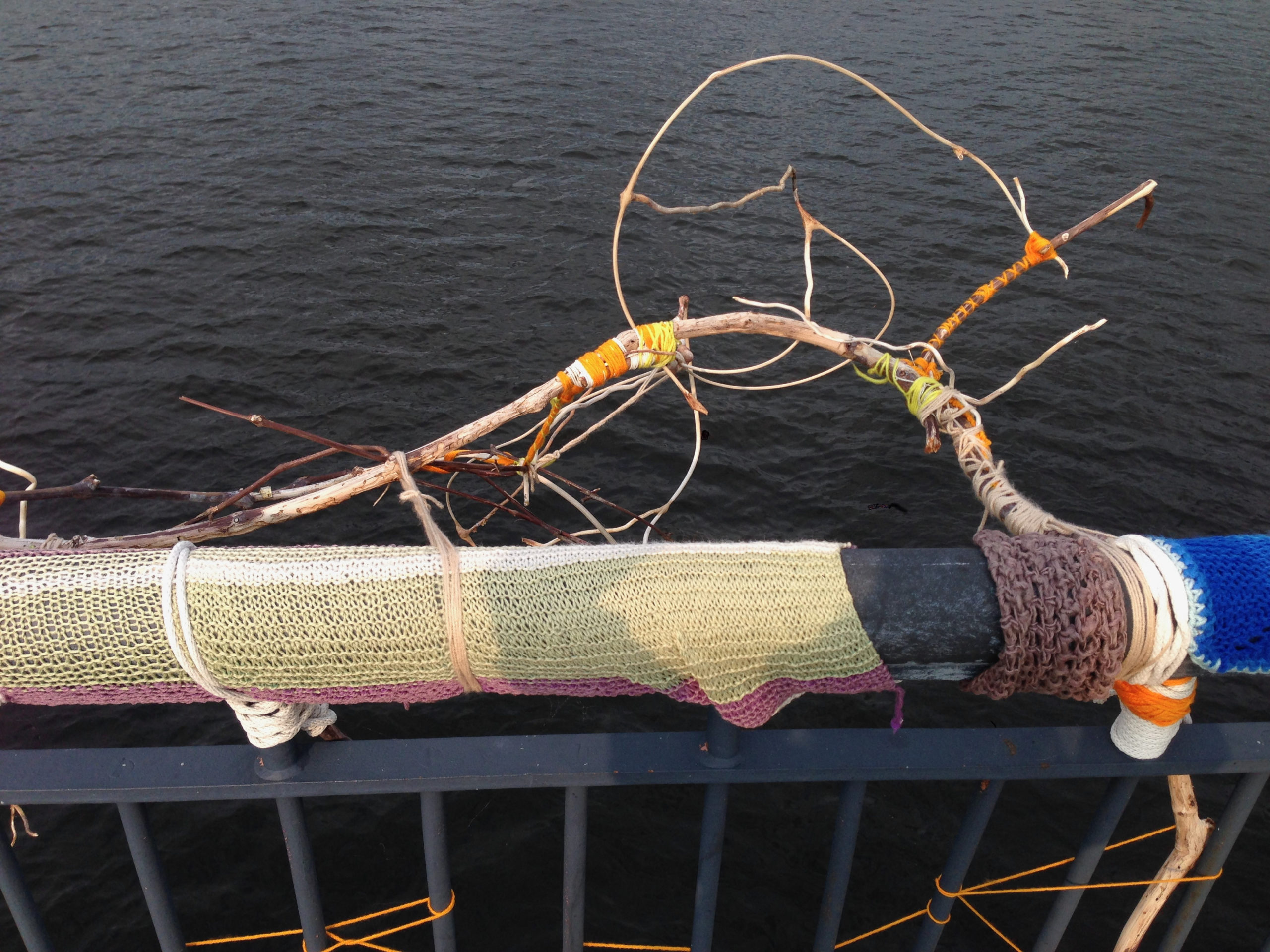

Sughra Raza. Yarn Art on The Mass Ave Bridge, July 2014.

Sughra Raza. Yarn Art on The Mass Ave Bridge, July 2014.