by Ed Simon

Demonstrating the utility of a critical practice that’s sometimes obscured more than its venerable history would warrant, my 3 Quarks Daily column will be partially devoted to the practice of traditional close readings of poems, passages, dialogue, and even art. If you’re interested in seeing close readings on particular works of literature or pop culture, please email me at [email protected]

On Valentine’s Day in 1990, the Voyager space-probe reoriented its camera in the direction of its origin, and was able to capture the furthest image of the Earth ever taken, from almost four billion miles away. Smaller than a single pixel, our world is suspended in a ribbon of luminescence, with Earth appearing as nothing so much as a solitary dust fragment captured in a ray of morning light. The picture was taken at the urging of astrophysicist and science popularizer Carl Sagan, who had worked on the original Voyager mission (and was famously involved with the compilation of its “Golden Record”). Acknowledging that there was little concrete scientific benefit to the image, Sagan had argued that reorienting the space probe’s camera so as to record Earth from such a distance would provide a perspective that would be culturally, philosophically, and spiritually beneficial. He considered the implications of that picture four years after it taken, in his celebrated work of science popularization Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space. A passage from that book, often informally referred to as “Reflections on a Mote of Dust,” asks the reader to “Look again at that dot.” What follows are five concise paragraphs wherein Sagan does just that, producing one of the most popular passages from a work of scientific journalism written in the past several decades.

Writing in The Atlantic, Marina Koren says that thirty years later, the Voyager image should be understood as a “display, however fuzzy, of humankind’s capacity to catapult away from our planet in an attempt to understand everything else.” Science correspondent for the BBC, Jonathan Amos, declares that the aqua sliver in a field of black is “unquestionably one of the greatest space images ever.” Meanwhile, Carolyn Porco at Scientific American exclaims that the picture “capped a groundbreaking era in the coming of age of our species.” Many peoples’ reactions to the picture, which if a viewer is unaware of what they’re looking at happens not to look like much of all, is understandably filtered through the experience of reading Sagan’s “Reflections on a Mote of Dust.” Perhaps the most talented and widely read popular science writer of the last quarter of the twentieth-century, Sagan was able to avoid the acerbic mean-spiritedness of a Richard Dawkins or the naïve scientificity of a Neil DeGrasse Tyson, writing rather in a poetic idiom that sacrificed nothing in the way of accuracy. Sagan rather belonged to an earlier grouping of scientist-explainers, figures like Stephen Jay Gould, Lewis Thomas, and Rachel Carson, who drew upon a rich vein of humanistic expression to use science as a means of contemplation and not just technocratic apologetics, making him a figure as reminiscent of the eighteenth or nineteenth-centuries as much as of the twentieth (in the best way). Read more »

When promoting her new book in September, Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett stated in an interview as quoted in Politico : “I think the Constitution is alive and well.” She went on – “I don’t know what a constitutional crisis would look like. I think that our country remains committed to the rule of law. I think we have functioning courts.”

When promoting her new book in September, Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett stated in an interview as quoted in Politico : “I think the Constitution is alive and well.” She went on – “I don’t know what a constitutional crisis would look like. I think that our country remains committed to the rule of law. I think we have functioning courts.” During covid, amid the maelstrom that was American healthcare, a miracle happened. State medical boards suspended their cross-state licensure restrictions.

During covid, amid the maelstrom that was American healthcare, a miracle happened. State medical boards suspended their cross-state licensure restrictions.

There has long been a temptation in science to imagine one system that can explain everything. For a while, that dream belonged to physics, whose practitioners, armed with a handful of equations, could describe the orbits of planets and the spin of electrons. In recent years, the torch has been seized by artificial intelligence. With enough data, we are told, the machine will learn the world. If this sounds like a passing of the crown, it has also become, in a curious way, a rivalry. Like the cinematic conflict between vampires and werewolves in the Underworld franchise, AI and physics have been cast as two immortal powers fighting for dominion over knowledge. AI enthusiasts claim that the laws of nature will simply fall out of sufficiently large data sets. Physicists counter that data without principle is merely glorified curve-fitting.

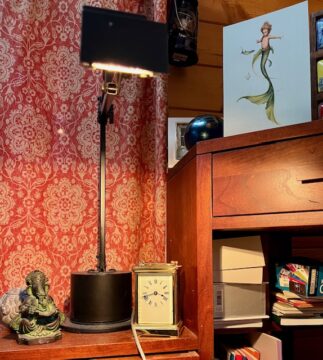

There has long been a temptation in science to imagine one system that can explain everything. For a while, that dream belonged to physics, whose practitioners, armed with a handful of equations, could describe the orbits of planets and the spin of electrons. In recent years, the torch has been seized by artificial intelligence. With enough data, we are told, the machine will learn the world. If this sounds like a passing of the crown, it has also become, in a curious way, a rivalry. Like the cinematic conflict between vampires and werewolves in the Underworld franchise, AI and physics have been cast as two immortal powers fighting for dominion over knowledge. AI enthusiasts claim that the laws of nature will simply fall out of sufficiently large data sets. Physicists counter that data without principle is merely glorified curve-fitting. The smallest spider I’ve ever seen is slowly descending from the little metal lampshade above my computer. She’s so tiny, a millimeter wide at most, I have to look twice to make sure she isn’t just a speck of dust. The only reason I can be certain that she’s not is that she’s dropping straight down instead of floating at random.

The smallest spider I’ve ever seen is slowly descending from the little metal lampshade above my computer. She’s so tiny, a millimeter wide at most, I have to look twice to make sure she isn’t just a speck of dust. The only reason I can be certain that she’s not is that she’s dropping straight down instead of floating at random. Naotaka Hiro. Untitled (Tide), 2024.

Naotaka Hiro. Untitled (Tide), 2024. In a previous essay,

In a previous essay,

Isn’t it time we talk about you?

Isn’t it time we talk about you?

To be alive is to maintain a coherent structure in a variable environment. Entropy favors the dispersal of energy, like heat diffusing into the surroundings. Cells, like fridges, resist this drift only by expending energy. At the base of the food chain, energy is harvested from the sun; at the next layer, it is consumed and transferred, and so begins the game of predation. Yet predation need not always be aggressive or zero-sum. Mutualistic interactions abound. Species collaborate when it conserves energy. For example, whistling-thorn trees in Kenya trade food and shelter to ants for protection. Ants patrol the tree, fending off herbivores from insects to elephants. When an organism cannot provide a resource or service without risking its own survival, opportunities for cooperative exchange are limited. Beyond the cooperative, predation emerges in its more familiar, competitive form. At every level, the imperative is the same: accumulate enough energy to maintain and reproduce. How this energy is obtained, conserved, or defended produces the rich diversity of strategies observed in nature.

To be alive is to maintain a coherent structure in a variable environment. Entropy favors the dispersal of energy, like heat diffusing into the surroundings. Cells, like fridges, resist this drift only by expending energy. At the base of the food chain, energy is harvested from the sun; at the next layer, it is consumed and transferred, and so begins the game of predation. Yet predation need not always be aggressive or zero-sum. Mutualistic interactions abound. Species collaborate when it conserves energy. For example, whistling-thorn trees in Kenya trade food and shelter to ants for protection. Ants patrol the tree, fending off herbivores from insects to elephants. When an organism cannot provide a resource or service without risking its own survival, opportunities for cooperative exchange are limited. Beyond the cooperative, predation emerges in its more familiar, competitive form. At every level, the imperative is the same: accumulate enough energy to maintain and reproduce. How this energy is obtained, conserved, or defended produces the rich diversity of strategies observed in nature.