by Mindy Clegg

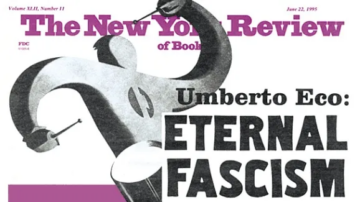

In a recent video by Damien Walter about the Polish sci-fi writer Stanislaw Lem, the role of the Holocaust is brought front and center in Lem’s body of work. According to academic and author Elena Gomel, his work demanded that we grapple with that incomprehensible event. It’s a question that matters still since in the modern era we continued to see violence with seemingly little reason. But, Walter argued, we have refused to learn a critical lesson from the Holocaust which is a form of denial of that horrific event: Lem’s insight that the Holocaust was not a deviation from the march of history, but a byproduct of modern history itself. One particular aspect of the Holocaust that Lem explored was the kitsch culture of the Nazis. Lem believed that kitsch had its worst expression in Nazi culture. Was Lem correct? Was there a direct line between kitsch culture and destructive states? Lem honed in on a key aspect of mass society and how it shapes us and is shaped by us. I would agree to a degree. Kitsch, a critical byproduct of modernity, has been both a means of reinforcing and resisting oppressive forms of power. At its worse it can be used to motivate awful forms of violence. But kitsch can also be wonderfully subversive. Read more »

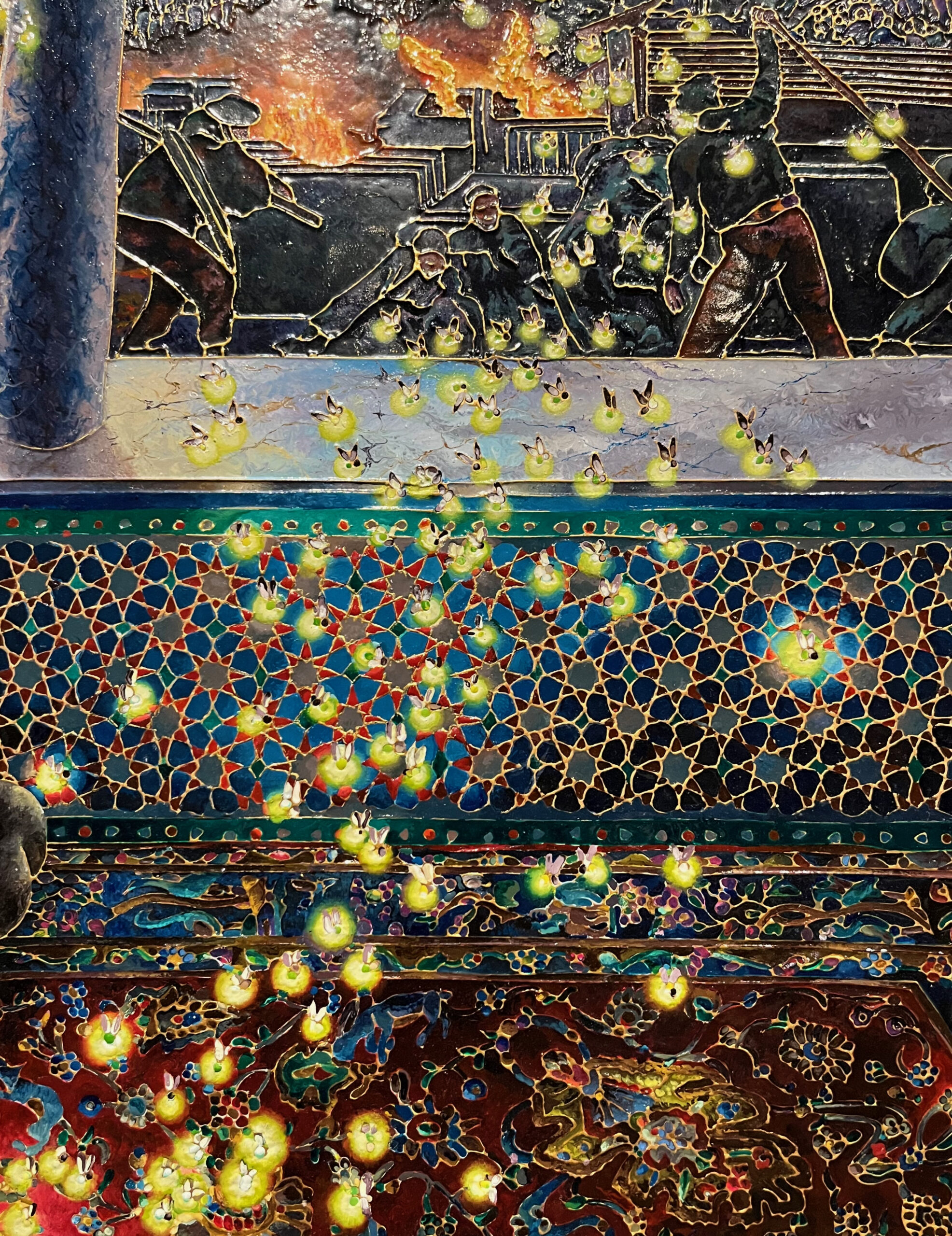

Raqib Shaw. Detail from Ode To a Country Without a Post Office, 2019-20. (photograph by Sughra Raza)

Raqib Shaw. Detail from Ode To a Country Without a Post Office, 2019-20. (photograph by Sughra Raza)

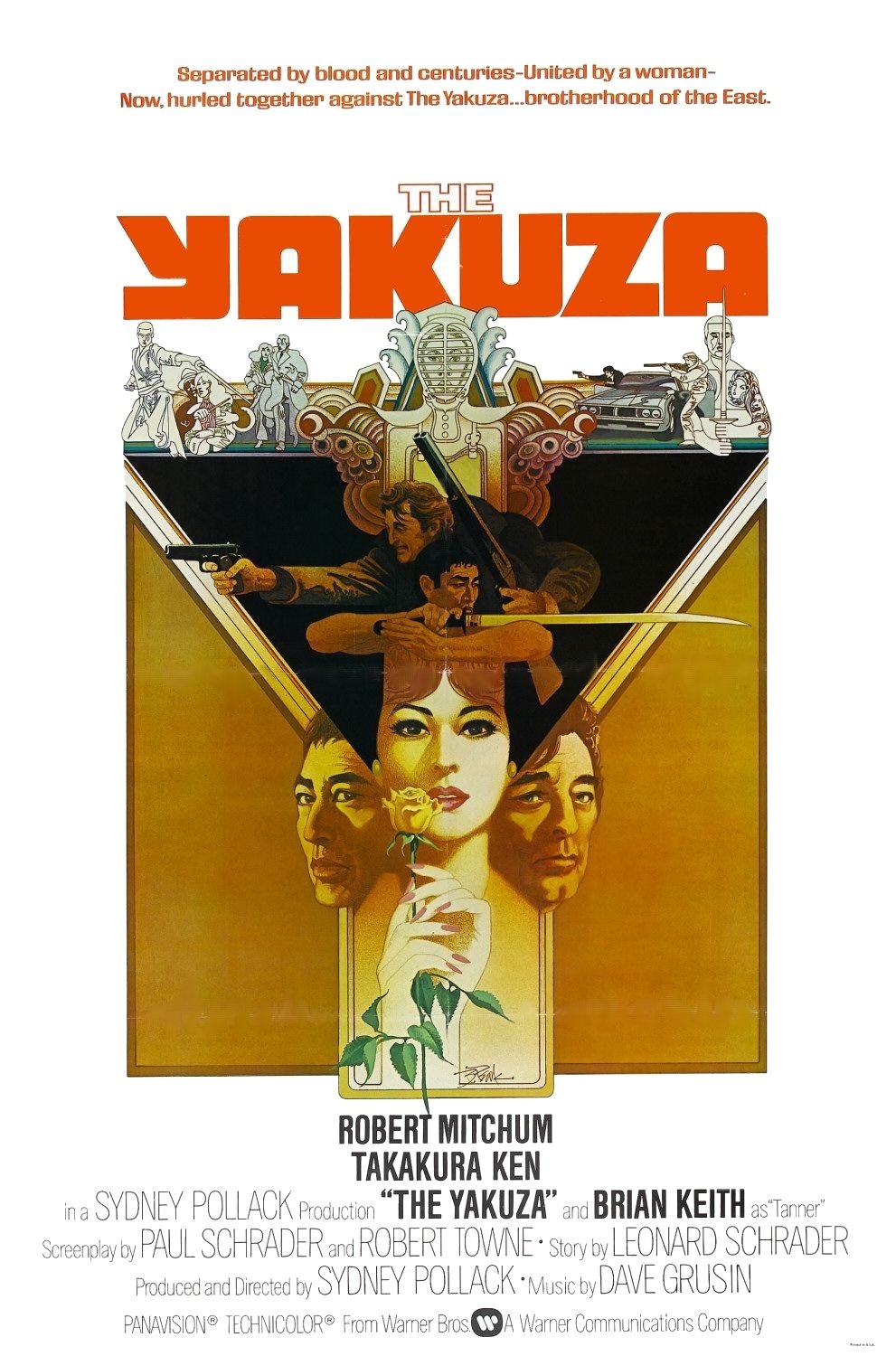

A few days ago I watched The Yakuza (1974), Paul Schrader’s screenwriting debut, and the following day I saw Andrei Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia (1983) at the cinema. These two films would never feature on a double bill together, and yet, due to having watched them within 24 hours of each other, they seem related in my mind, and I can’t help but interpret Nostalghia in light of The Yakuza.

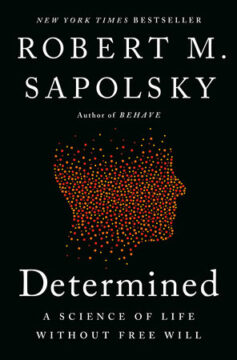

A few days ago I watched The Yakuza (1974), Paul Schrader’s screenwriting debut, and the following day I saw Andrei Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia (1983) at the cinema. These two films would never feature on a double bill together, and yet, due to having watched them within 24 hours of each other, they seem related in my mind, and I can’t help but interpret Nostalghia in light of The Yakuza. A few months ago, the Stanford biologist Robert Sapolsky released

A few months ago, the Stanford biologist Robert Sapolsky released