by Tim Sommers

The Theory of Mind That Says Artificial Intelligence is Possible

Does your dog feel pain? Or your cat? Surely, nonhuman great apes do. Dolphins feel pain, right? What about octopuses? (That’s right, “octopuses” not “octopi.”)They seem to be surprisingly intelligent and to exhibit pain-like behavior – even though the last common ancestor we shared was a worm 600 million years ago.

Given that all these animals (and us) experience pain, it seems exceedingly unlikely that there would only be a single kind of brain or neurological architecture or synapse that could provide the sole material basis for pain across all the possible beings that can feel pain. Octopuses, for example, have a separate small brain in each tentacle. This implies that pain, and other features of our psychology or mentality, can be “multiply realized.” That is, a single mental kind or property can be “realized,” or implemented (as the computer scientists prefer), in many different ways and supervene on many distinct kinds of physical things.

We don’t have direct access to the phenomenal properties of pain (what it feels like) in octopuses – or in fellow humans for that matter. I can’t feel your pain, in other words, much less my pet octopuses’. So, when we say an octopus feels pain like ours, what can we mean? What makes something an example (or token) of the mental instance (or type) “pain”? The dominant answer to that question in late twentieth century philosophy was called the “functionalism” answer (though many think functionalism goes all the way back to Aristotle).

Functionalism is the theory that what makes something pain does not depend on its internal constitution or phenomenal properties, but rather the role or function it plays in the overall system. Pain might be, for example, a warning or a signal of bodily damage. What does functionalism say about the quest for Artificial General Intelligence (AGI)? Read more »

I’ve heard owls are signs of a big shift in your life; I also know that I only really look for owls during those times.

I’ve heard owls are signs of a big shift in your life; I also know that I only really look for owls during those times.  The

The  Poets. Dancers. Singers. Scientists. Generals. Explorers. Actors. Engineers. Diplomats. Reformers. Painters. Sailors. Builders. Climbers. Composers. In a pretty-good eighteenth-century copy of a portrait by Holbein the Younger, Thomas Cromwell is not so much a man as a slab of living, dangerous gristle. Henry James looks dangerous too, in a portrait by John Singer Sargent that more people would recognize as great if inverted snobbery hadn’t turned under-rating Sargent into a whole academic discipline. Humphrey Davy, painted in his forties, could not be more different. He looks about 14; thinking about science has made him glow with delight.

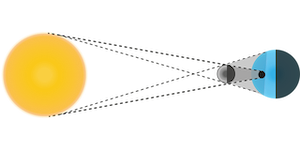

Poets. Dancers. Singers. Scientists. Generals. Explorers. Actors. Engineers. Diplomats. Reformers. Painters. Sailors. Builders. Climbers. Composers. In a pretty-good eighteenth-century copy of a portrait by Holbein the Younger, Thomas Cromwell is not so much a man as a slab of living, dangerous gristle. Henry James looks dangerous too, in a portrait by John Singer Sargent that more people would recognize as great if inverted snobbery hadn’t turned under-rating Sargent into a whole academic discipline. Humphrey Davy, painted in his forties, could not be more different. He looks about 14; thinking about science has made him glow with delight.  There are worse places to be a stargazer than south-central Indiana; it’s not cloudy all the time here. I’ve spent many lovely evenings outside looking at stars and planets, and I’ve been able to see a fair number of lunar eclipses, along with the occasional conjunction (when two or more planets appear very close together on the sky) and, rarely, an occultation (when a celestial body, typically the moon but sometimes a planet or asteroid, passes directly in front of a planet or star).

There are worse places to be a stargazer than south-central Indiana; it’s not cloudy all the time here. I’ve spent many lovely evenings outside looking at stars and planets, and I’ve been able to see a fair number of lunar eclipses, along with the occasional conjunction (when two or more planets appear very close together on the sky) and, rarely, an occultation (when a celestial body, typically the moon but sometimes a planet or asteroid, passes directly in front of a planet or star).

Sughra Raza. Figure in Environment, May 1974.

Sughra Raza. Figure in Environment, May 1974.

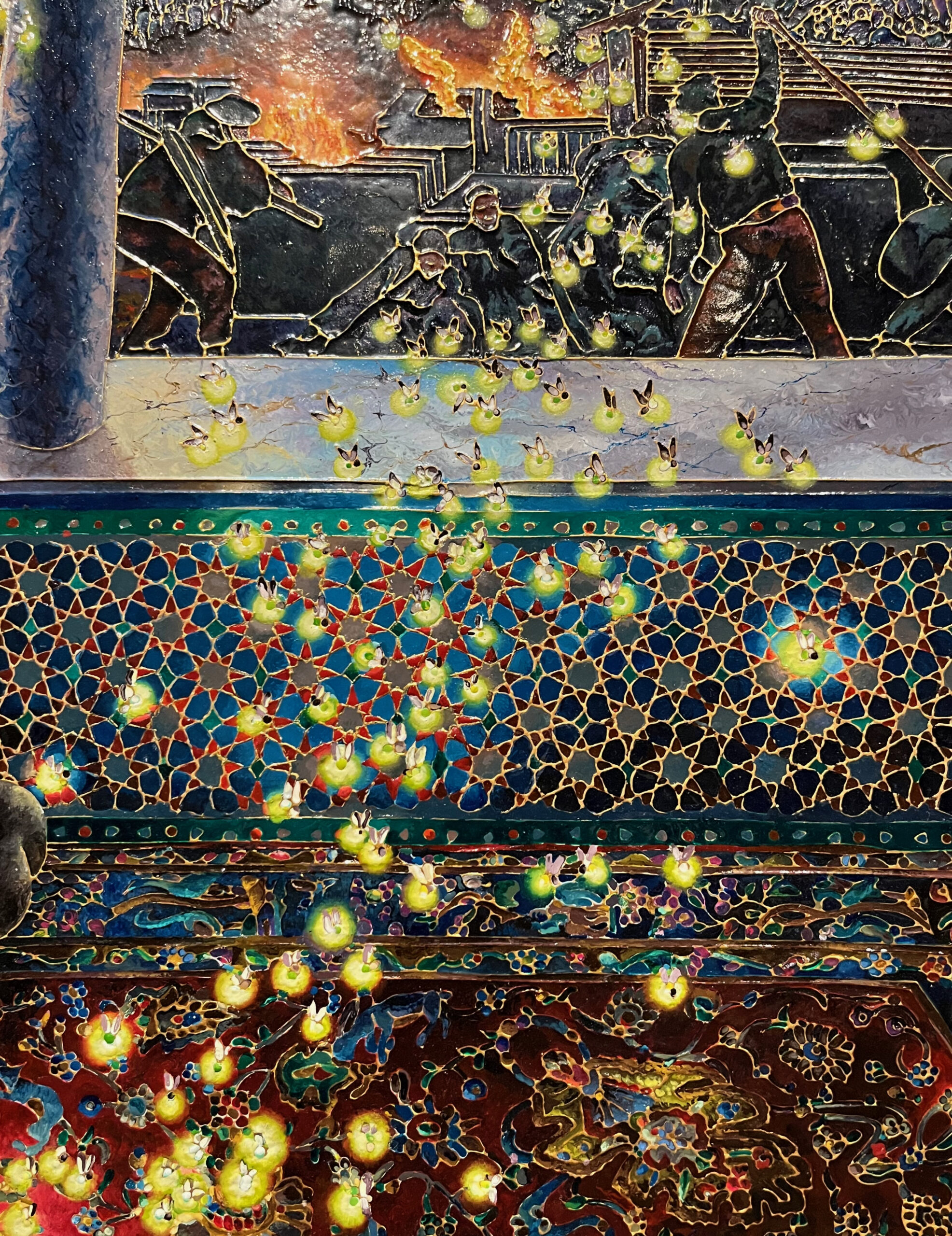

Raqib Shaw. Detail from Ode To a Country Without a Post Office, 2019-20. (photograph by Sughra Raza)

Raqib Shaw. Detail from Ode To a Country Without a Post Office, 2019-20. (photograph by Sughra Raza)