by Oliver Waters

The Matrix films depict a future dystopia in which oppressive super-intelligent machines have imprisoned human beings inside an entirely simulated world in order to exploit them as a power source. The human protagonists of the films – Neo and Trinity – lead a thrilling rebellion to free as many people as possible. It’s rather obvious why they are the ‘good guys’ and the machines are evil: imprisoning people in a virtual cage is wrong.

The Matrix films depict a future dystopia in which oppressive super-intelligent machines have imprisoned human beings inside an entirely simulated world in order to exploit them as a power source. The human protagonists of the films – Neo and Trinity – lead a thrilling rebellion to free as many people as possible. It’s rather obvious why they are the ‘good guys’ and the machines are evil: imprisoning people in a virtual cage is wrong.

This is despite the fact that life in the Matrix actually seems more enjoyable than the alternative. Inside, you partake in the heady optimistic era of 1990s America. Outside it, you must endure the dusty remnants of the great civilisational war between humans and machines. There isn’t even any sunshine, on account of the humans having ‘scorched the sky’ to prevent the machines from accessing solar power. The only ‘free’ human city exists deep underground, where there’s very little entertainment unless scantily clad festival raves are your thing.

This is why the notorious character Cypher decides to betray humanity to the machines in exchange for a charmed life in the simulation. As he rationalises while eating a juicy virtual steak: ‘ignorance is bliss’. The film pushes us to think of Cypher as a deeply mistaken jerk. But why exactly? Why is being trapped in the Matrix wrong even if it is seemingly more pleasurable than living in reality? Because it is assumed that the people stuck inside it possess the inherently human trait of curiosity. Deep down, they want to know how the world really works. By being trapped in a fantasy world, this basic need is being frustrated, even if they don’t know it. Their individual potentials as self-aware beings are being cruelly inhibited, and justice demands that they be freed.

If you haven’t seen the Matrix films by now – where on Earth have you been?

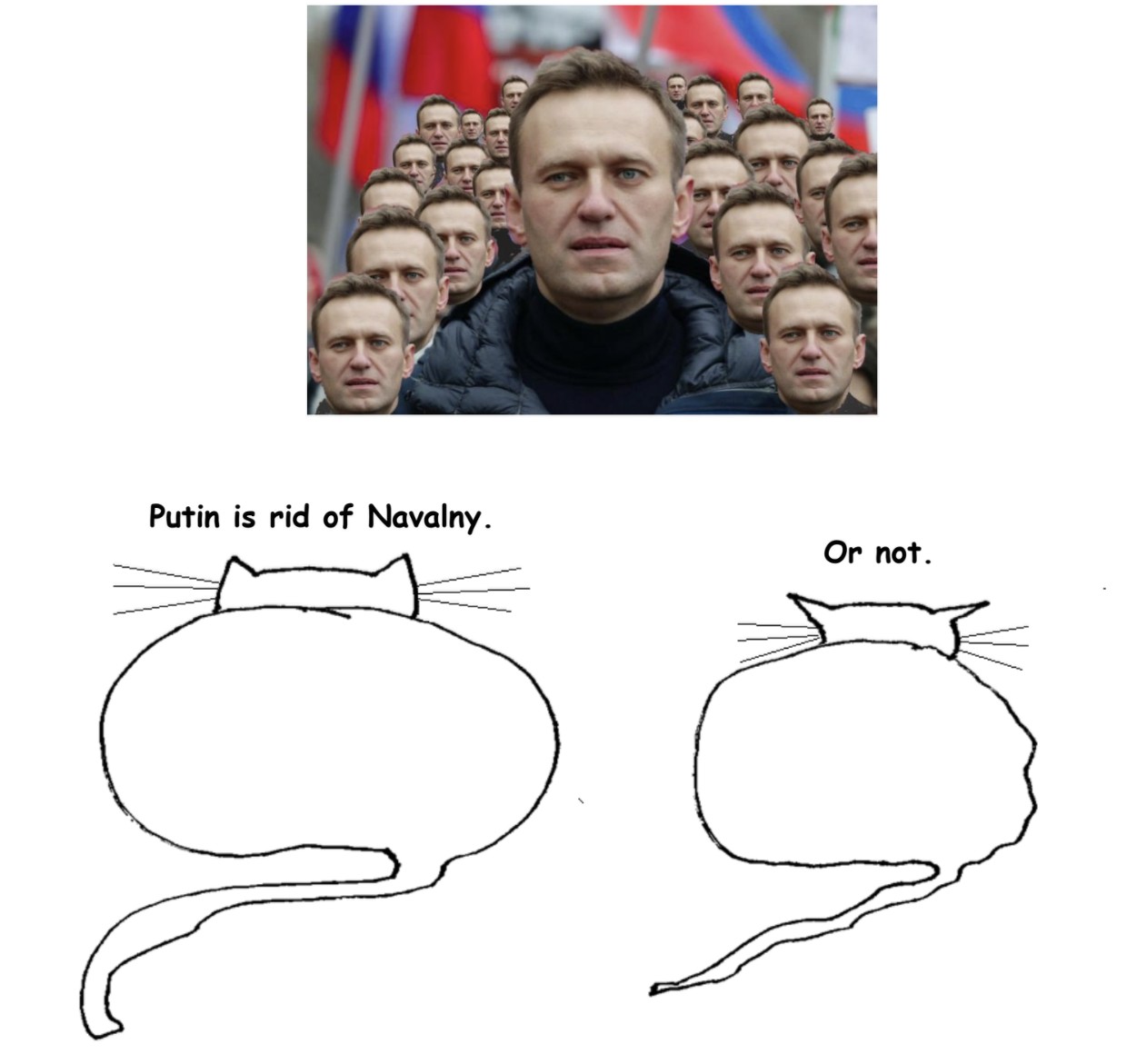

One plausible place is on North Sentinel Island, a tiny member of the Andaman Islands in the Bay of Bengal. It is remarkable for the fact that the people who live on it (the ‘Sentinelese’) are in almost zero contact with the rest of our global civilisation. There have been several attempts to connect with them over the centuries with varying degrees of failure, brought vividly to life in Adam Goodheart’s recent book The Last Island (2023). The Sentinelese exist today in total isolation – an arrangement enforced by the Indian government within whose sovereignty the island lies. Read more »

Poets. Dancers. Singers. Scientists. Generals. Explorers. Actors. Engineers. Diplomats. Reformers. Painters. Sailors. Builders. Climbers. Composers. In a pretty-good eighteenth-century copy of a portrait by Holbein the Younger, Thomas Cromwell is not so much a man as a slab of living, dangerous gristle. Henry James looks dangerous too, in a portrait by John Singer Sargent that more people would recognize as great if inverted snobbery hadn’t turned under-rating Sargent into a whole academic discipline. Humphrey Davy, painted in his forties, could not be more different. He looks about 14; thinking about science has made him glow with delight.

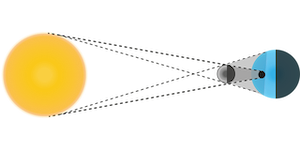

Poets. Dancers. Singers. Scientists. Generals. Explorers. Actors. Engineers. Diplomats. Reformers. Painters. Sailors. Builders. Climbers. Composers. In a pretty-good eighteenth-century copy of a portrait by Holbein the Younger, Thomas Cromwell is not so much a man as a slab of living, dangerous gristle. Henry James looks dangerous too, in a portrait by John Singer Sargent that more people would recognize as great if inverted snobbery hadn’t turned under-rating Sargent into a whole academic discipline. Humphrey Davy, painted in his forties, could not be more different. He looks about 14; thinking about science has made him glow with delight.  There are worse places to be a stargazer than south-central Indiana; it’s not cloudy all the time here. I’ve spent many lovely evenings outside looking at stars and planets, and I’ve been able to see a fair number of lunar eclipses, along with the occasional conjunction (when two or more planets appear very close together on the sky) and, rarely, an occultation (when a celestial body, typically the moon but sometimes a planet or asteroid, passes directly in front of a planet or star).

There are worse places to be a stargazer than south-central Indiana; it’s not cloudy all the time here. I’ve spent many lovely evenings outside looking at stars and planets, and I’ve been able to see a fair number of lunar eclipses, along with the occasional conjunction (when two or more planets appear very close together on the sky) and, rarely, an occultation (when a celestial body, typically the moon but sometimes a planet or asteroid, passes directly in front of a planet or star).

Sughra Raza. Figure in Environment, May 1974.

Sughra Raza. Figure in Environment, May 1974.

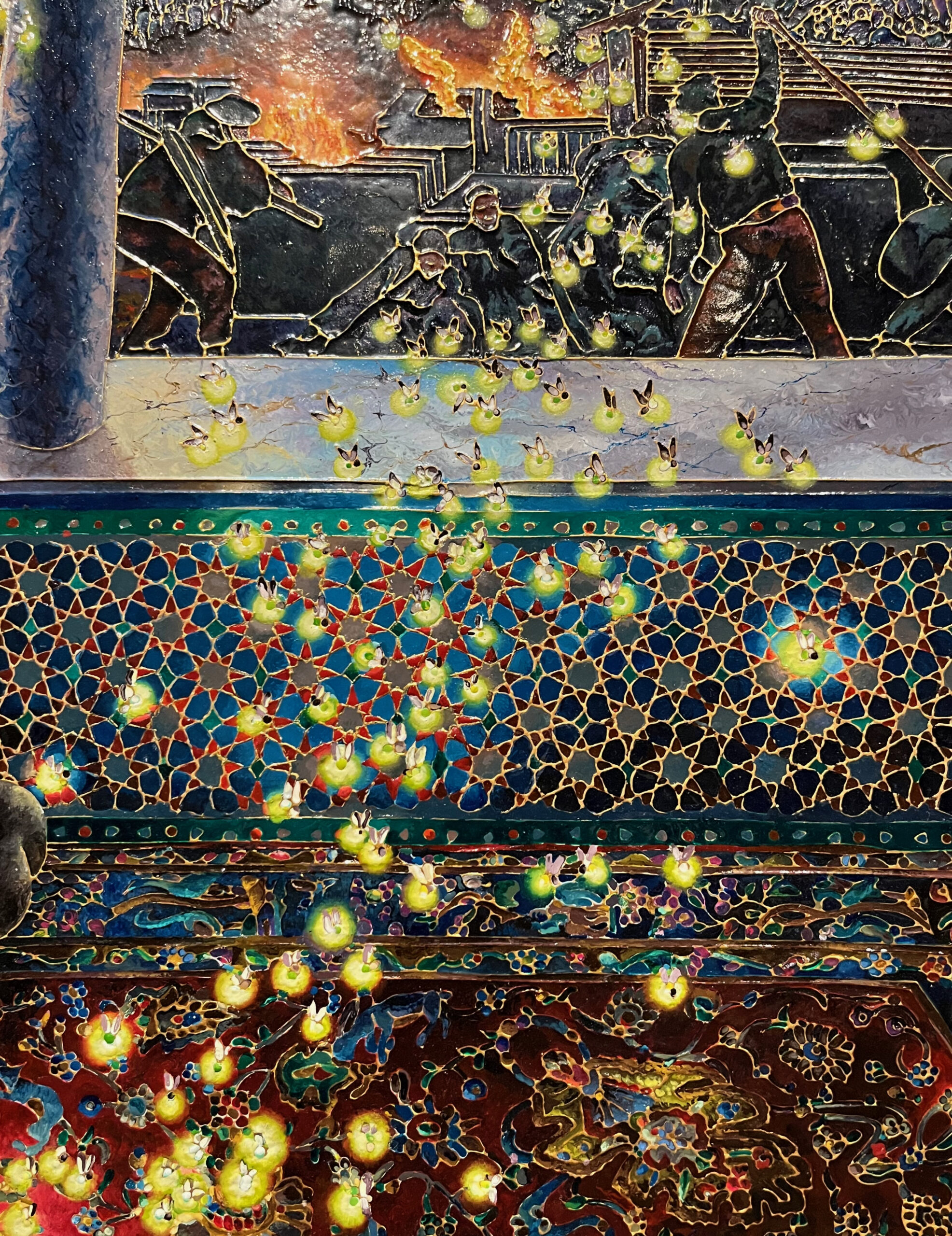

Raqib Shaw. Detail from Ode To a Country Without a Post Office, 2019-20. (photograph by Sughra Raza)

Raqib Shaw. Detail from Ode To a Country Without a Post Office, 2019-20. (photograph by Sughra Raza)