by Bill Murray

Countries can be sensitive as teenage girls about their names. The change from Turkey to Türkiye aligned Türkiye’s name in Turkish with its internationally known name, but mainly, disassociated itself from the bird with the goofy reputation.

Some countries’ names become less ethnic (Zaire to Democratic Republic of the Congo) and others more (Swaziland to Eswatini). Some countries change their names for politics (Macedonia to North Macedonia).

They say Czechia changed its name for marketing. Moldova may not need a name change, but it could maybe use some rebranding. The state news agency is Moldpres and the phone company is Moldtelecom. Sounds vaguely unhygienic.

But on substance and politics, the three-and-a-half-year government of 52-year-old Maia Sandu in Chișinău, Moldova’s capital, is playing a shaky hand like a poker shark, navigating a small agrarian nation riven into parts toward the West, with many thanks to Russia’s war on Ukraine.

Moldova borders only Romania and Ukraine. Its fate is tied utterly to the war. To be clear right up front, I wanted to visit this summer because, depending on the outcome of the war, visiting later might not be possible, maybe for a long time.

Like everywhere else, Moldova’s electorate is divided. President Sandu’s pro-Russian predecessor Igor Dodon has been charged with all manner of crimes by all manner of authorities Moldovan and Western, crimes of high treason, corruption and racketeering. The U.S. Treasury has piled on with conspiracy charges. These charges have left Dodon effectively neutered as a political player for now.

Sandu’s most prominent current challenger, Ilan Shor, is only 37 years old. The former mayor of a Moldovan town of 20,000 called Orhei, Shor was convicted in 2017 in a fraud scheme that cost the country about a billion dollars, or 12% of its GDP at the time. Read more »

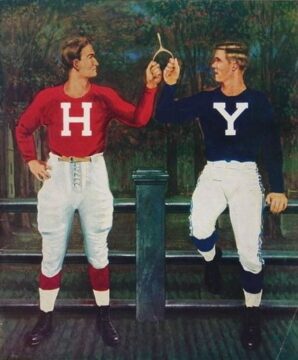

This week marks one year since Affirmative Action was repealed by the Supreme Court. The landmark ruling was a watershed moment in how we think of race and social mobility in the United States. But for high schoolers, the crux of the case lies somewhere else entirely.

This week marks one year since Affirmative Action was repealed by the Supreme Court. The landmark ruling was a watershed moment in how we think of race and social mobility in the United States. But for high schoolers, the crux of the case lies somewhere else entirely.

Arguably the greatest global health policy failure has been the US Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) refusal to promulgate any regulations to first mitigate and then eliminate the healthcare industry’s significant carbon footprint.

Arguably the greatest global health policy failure has been the US Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) refusal to promulgate any regulations to first mitigate and then eliminate the healthcare industry’s significant carbon footprint.

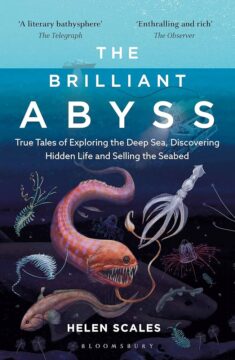

Marine biologist Helen Scales’ previous book The Brilliant Abyss: True Tales of Exploring the Deep Sea, Discovering Hidden Life and Selling the Seabed, brilliantly provided us with a glimpse of the wondrous life forms that inhabit the abyss, the deep sea. She also made known her profound concern for the future of ocean life posed by human activity. She now expands on those issues and concerns in her new book, What The Wild Seas Can Be: The Future of the World’s Seas. Scales provides us with a fascinating exposition of the pre-historic ocean and the devastating impact of the Anthropocene on ocean life over the last fifty years. Her main concern, however, is the future of the ocean and her new book makes a major contribution to people’s understanding of the repercussions of human activity on ocean life and the measures that need to be taken to protect and secure a better future for the ocean.

Marine biologist Helen Scales’ previous book The Brilliant Abyss: True Tales of Exploring the Deep Sea, Discovering Hidden Life and Selling the Seabed, brilliantly provided us with a glimpse of the wondrous life forms that inhabit the abyss, the deep sea. She also made known her profound concern for the future of ocean life posed by human activity. She now expands on those issues and concerns in her new book, What The Wild Seas Can Be: The Future of the World’s Seas. Scales provides us with a fascinating exposition of the pre-historic ocean and the devastating impact of the Anthropocene on ocean life over the last fifty years. Her main concern, however, is the future of the ocean and her new book makes a major contribution to people’s understanding of the repercussions of human activity on ocean life and the measures that need to be taken to protect and secure a better future for the ocean.

In this conversation—excerpted from the Aga Khan Award for Architecture’s upcoming volume, Beyond Ruins: Reimagining Modernism (ArchiTangle, 2024) set to be published this Fall, and focusing on the renovation of the Niemeyer Guest House by East Architecture Studio in Tripoli, Lebanon—

In this conversation—excerpted from the Aga Khan Award for Architecture’s upcoming volume, Beyond Ruins: Reimagining Modernism (ArchiTangle, 2024) set to be published this Fall, and focusing on the renovation of the Niemeyer Guest House by East Architecture Studio in Tripoli, Lebanon—

Michael Wang. Holoflora, 2024

Michael Wang. Holoflora, 2024 In the game of chess, some of the greats will concede their most valuable pieces for a superior position on the board. In a 1994 game against the grandmaster Vladimir Kramnik, Gary Kasparov sacrificed his queen early in the game with a move that made no sense to a middling chess player like me. But a few moves later Kasparov won control of the center board and marched his pieces into an unstoppable array. Despite some desperate work to evade Kasparov’s scheme, Kramnik’s king was isolated and then trapped into checkmate by a rook and a knight.

In the game of chess, some of the greats will concede their most valuable pieces for a superior position on the board. In a 1994 game against the grandmaster Vladimir Kramnik, Gary Kasparov sacrificed his queen early in the game with a move that made no sense to a middling chess player like me. But a few moves later Kasparov won control of the center board and marched his pieces into an unstoppable array. Despite some desperate work to evade Kasparov’s scheme, Kramnik’s king was isolated and then trapped into checkmate by a rook and a knight.

In Discourse on the Method, philosopher René Descartes reflects on the nature of mind. He identifies what he takes to be a unique feature of human beings— in each case, the presence of a rational soul in union with a material body. In particular, he points to the human ability to think—a characteristic that sets the species apart from mere “automata, or moving machines fabricated by human industry.” Machines, he argues, can execute tasks with precision, but their motions do not come about as a result of intellect. Nearly four-hundred years before the rise of large language computational models, Descartes raised the question of how we should think of the distinction between human thought and behavior performed by machines. This is a question that continues to perplex people today, and as a species we rarely employ consistent standards when thinking about it.

In Discourse on the Method, philosopher René Descartes reflects on the nature of mind. He identifies what he takes to be a unique feature of human beings— in each case, the presence of a rational soul in union with a material body. In particular, he points to the human ability to think—a characteristic that sets the species apart from mere “automata, or moving machines fabricated by human industry.” Machines, he argues, can execute tasks with precision, but their motions do not come about as a result of intellect. Nearly four-hundred years before the rise of large language computational models, Descartes raised the question of how we should think of the distinction between human thought and behavior performed by machines. This is a question that continues to perplex people today, and as a species we rarely employ consistent standards when thinking about it. The human tendency to anthropomorphize AI may seem innocuous, but it has serious consequences for users and for society more generally. Many people are responding to the

The human tendency to anthropomorphize AI may seem innocuous, but it has serious consequences for users and for society more generally. Many people are responding to the